For a very long time children had no role in archaeology. Child’s play, children’s toys, the life and health of children, and children’s roles in society were seldom mentioned in archaeological field dig reports. Children, toys, and games and children’s material cultures were almost never mentioned at learned meetings and symposia. When archaeologists did dig what were apparently children’s artifacts, they all too often attributed them either to adults or they categorized them as play-tools used to teach and to prepare children for adult roles.

In other words, when children were encountered in the field they were viewed through the lens of adults. Children’s artifacts were subsumed under similar adult artifacts. They were invisible children.[1]

What’s Going On?

We have written about these almost universal practices in Chapter 4, “Pensacola Canicas Para Oficiciales Militares” in our book The Secret Life of Marbles Their History and Mystery, in our Post Native American Marbles and Games (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/native-american-marbles-games/), and in many sections of other writings.

Certainly, some scientists and historians do mention toys. One notable example is Jeff Carskadden and Richard Gartley.[2]

While we have read any number of proposed reasons why children’s culture has become a research subset within archaeology, and while we find some theories practically uncorroborated, we will leave that research to someone else.

Welcome Children!

We are just excited that children are finally getting their due in literature. One reason we are so grateful that children have appeared in the historical and archaeological literature is that now, finally, marbles, are being reported in field dig reports and in museum accessions! After all, they have always been there!

We are certainly not going to list an annotated bibliography about children’s material culture in archaeology, although one is needed, but we do want to give you some idea of what is being dug in the field. In fact, there has never been as many toys and other children’s artifacts reported in the literature as there are today!

Where They Rightfully Belong

Where They Rightfully Belong

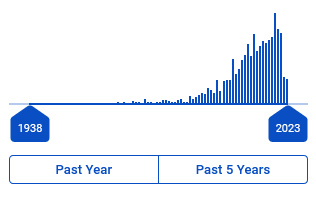

This filter screen grab from Academia.edu is certainly not a scientific representation of the actual growth in the academic literature about children’s material culture. Nor is it intended to be.

Academia.edu “… is a platform for sharing academic research. Academics have uploaded 47 million papers, and 86 million academics, professionals, and students read papers on Academia every month.”[3] When we search Academia using keywords like “children in archaeology” or “children’s toys in archaeology,” this diagram is the visual result of a filtered search. Regardless of the topic we are researching, we have always found relevant papers at Academia.edu.

The bottom line is this: children are finally being recognized as integral if one wants to understand the full historical story. And marbles and other children’s toys, many designed and made by children themselves, are key markers in any archaeological dig.

Here are just a few glimpses of Marbles in the field!

Dąbal and Key Markers

Joanna Dąbal[4] not only discusses dug marbles, but she also provides a photograph of them as well as an antique print of children playing games with marbles in the foreground.

Dąbal discusses an archaeological dig at Stara Stocznia /Wałowa 56 Street located in the City Centre of Gdańsk, Poland. Under the heading “Marbles” on page 142 she writes that

“a total number of 21 ceramic marbles were found related to leveling layers. 10 of them were excavated of the 17th-century levels …. Only a single one has been deposited in the 18th-century layer …. The remaining 9 objects … were dated somewhere between the 18th to the half of the 19th century. The last find is associated with the 20th-century destruction level…. All marbles were made of red clay. Single objects were additionally lead glazed. The sizes of the marbles range between 13 to 18 mm in diameter. The majority of finds is sized 16 mm.… Ceramic balls are attributed to children’s games and adult gambling.”

13 mm is just over ½” while 18 mm is slightly less than ¾”. And, of course, 16 mm is our familiar ⅝” player marble. We find the mention of lead glazing interesting, and we would like to learn more about that.

Stratigraphy…Or Where You Find Them

Some of us have field practice in archaeology or we have been on digs at old marble sites. The fundamental proposition of archaeology is stratigraphy or what Dąbal refers to as “leveling”.

“Stratigraphy is the study of layered materials (strata) that were deposited over time. The basic law of stratigraphy, the law of superposition, states that lower layers are older than upper layers, unless the sequence has been overturned.”[5]

And it is abundantly obvious when working on a site that one or more layers of strata have been disturbed; often diggers backfield the hole that they dug.

It is because of this law of superposition that an archaeological dig may move at a snail’s pace. If diggers do find a marbles in a layer, as Dąbal reports, then it is also critically important to map out and record not only the position of the marble in the strata but also any and all other artifacts which may lie adjacent to the marble.

Toy Munitions

A little more than twenty years ago Larry first became aware of all the invisible children in the field practice of archaeology. Larry’s sister gifted us with a very nice clutch of stone marbles. However the marbles had neither provenance nor provenience. We already knew that archaeologist preferred artifacts, like stone marbles, in situ. As Dąbal reports, artifacts are dug in layers or levels, and each level may be a different time period.

Still, Larry took the stone marbles to a number of archaeologists and asked for some type identification taking into consideration their ex situ condition: no idea where they were dug, if they were found, and no idea what other artifacts may have been found with them.

Without an exception and independent of each other each scientist, historian, anthropologist, and even retiree volunteers identified the stone marbles as shot. Munitions.

We know that marbles have been used as munitions. Check our story “Marbles Used as Munitions in the American Civil War” (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/marbles-were-used-as-munitions/).

But not all “elusive artifacts”—things that the scientist cannot identify when he or she pulls it out of the ground nor later in the lab—are munitions. Nor are they all that other catchall category “ritual”.

Ritual

In her story “Why Ancient Toys Are Elusive Artifacts” online at Discovery Magazine[6] Bridget Alex tells us that “children have always played. But evidence of their pretend worlds and games is hidden in the archeological record.” She continues:

“When confronting enigmatic finds, researchers traditionally assumed ritual was the cause, and did not consider kids’ play. There’s even a joke among archaeologists: If you can’t explain some discovery, like a painted bear skull or a pile of colorful stones, say ‘It’s ritual.’”

Langley and Litster[7] agree.

“Applying the adage ‘it’s ritual’ to any object or pattern in the archaeological record that cannot be explained by economic or technological activities has long been commonplace in archaeology. And while in many cases such interpretations may be correct, we researchers routinely overlooked another agent that equally, and perhaps more frequently, can be responsible for such discoveries — children.”

Munitions

Or, depending on the dig site (is it inside a fort or on a known battlefield?) archaeologists simply call the toy munitions. Notice that when dug artifacts cannot be identified by the scientists or when artifacts seem to be at the “wrong” strata, then they are often assigned to ritual or to war. Remember what we said at the outset: unfamiliar or “wonky”[8] artifacts are viewed through the lens of the adult. This is because until very recently there was no lens for the child!

Not only were children invisible at archaeology dig sites and in museums, but so were their toys and playthings!

After all in the case of stone marbles who could possibly challenge your assessment of them as bullets? No one can possibly prove you wrong!

Check this photograph carefully. There are clay marbles in the display box. There are stone marbles in the box. And absolutely guaranteed there is one or more bullets or munitions in the box. Without any further information, can you tell which is which? If you can then please click the “Contact” button and clear things up for us!

Revolutionary War Camp in New York City

We had fun recently with the Post “Time Rolls like a Marble: Marbles in Colonial America and the Revolution” (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/time-rolls-like-a-marble-marbles-in-colonial-america-the-revolution/). In the late 1940s and early 1950s any number of archaeologist, some trained and some “amateur”, were searching for artifacts from Revolutionary War camps in New York City. No one was looking for marbles in an 1700s Army camp. But that’s what they found.

Calver and Bolton[9], in a paper published in 1950, write:

“Frequently when we reached for a bullet in the sieve[10] it turned out to be a child’s marble. Bits of school slates, and slate pencils, fragments of a porcelain doll, and an earthenware woolly lamb convinced the diggers …that others than grown-ups occupied the camps, and that little children amid the hubbub of military life about them practiced the pastimes of their kind.”

These authors have a good deal more to say about both women and children in the camps. And there are historical records which corroborate their field work.

Invisible Children

So far we have established the obvious fact that children have been present throughout all of human history. Some lived in the country; some lived in squalid cities. They were in Army camps throughout history and all across the globe. Many were confined to refugee camps. And they played. They always played. They played and they left toys behind which could establish a rich vein in history which has never been fully explored. But until recently children and their toys were invisible in the archaeological record. Let’s see what just a few more scientists have to say about what they found about children, games, and toys at dig sites.

Diggin in the Cesspit with Marjin

Marijin Stolk’s doctoral dissertation The archaeology of Vlooienburg Materiality and daily life in multicultural Amsterdam, 1600 – 1800[11] is both a work of art and a masterful and informative thesis. Stolk writes:

“The cesspit finds that formed the core of the research project were recovered from excavations by the Amsterdam city archaeologists, which took place in the current Waterlooplein area between 1981 and 1982. These waste pits – which had been used as latrines as well as for the dump of household waste – offered an extraordinarily rich assemblage of artefacts of a great diversity of floral and faunal remains, all of an exceptional quality and quantity (page 1).

…. It is widely believed among archaeologists that data from cesspits are a precious source of information, and may be used to reconstruct the daily life from past centuries. The household waste contained in cesspits often presents a combination of material culture, food remains and sometimes waste from craft activities, revealing a glimpse of past daily life with all of its customs, habits and skills. Material studies on finds from cesspits… have been used in research on social stratigraphy, and ecological remnants have been studied to investigate past dietary habits.

The use of pits, old water wells and latrines for waste management is something that is seen in many different regions and time periods, although the concept of the cesspit – or beerput in Dutch – with a clear combined function of privy and trash dump – becomes a more common phenomenon in towns and cities in the Netherlands from the 14th century onwards” (page 14).

Marbles in the Pit

A remarkable number of marbles have been found in latrines, privies, and cesspits! We have explored the topic of marbles found in community latrines in China in Chapter 8 “Shanghai Stinkers” in our book The Secret Life of Marbles Their History and Mystery as well as in private outhouses in our Post “You Dug it up Where?” https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/you-dug-it-up-where/

Section 5.3 of Stolk’s thesis is “Toys and Gaming Pieces”. In this section Stolk notes that “when discussing toys within an archaeological assemblage, it is important to distinguish between toys, which were specifically designed for children, and gaming items, which might also have been used by adolescents and/or adults. Amongst the toys that directly relate to children, we can include objects such as dolls, spinning tops and marbles…”(page 147).

While we learned a lot from Stolk’s thesis, the most critical information for us comes on page 148. As noted we have kicked around archaeological digs for over twenty years and have studied history both in the library and in the field for well over sixty years. We have never seen anything like what Stolk reports was found in the ancient Amsterdam cesspits. And we never thought we would see anything like it.

What Was In There?

Stolk tells us about the finds on page 148.

“The most frequently found type of toys and gaming pieces which can be related to children, are ceramic, stone, and glass marbles …. One possible explanation for the large number of retrieved marbles from Vlooienburg is that it was an easily accessible game and that marbles were inexpensive. Losing a marble or intentionally throwing them away in a cesspit may not have been a great loss for its owner.”

It is simply astounding how the art and science of archaeology has changed! We have been on sanctioned digs and have read a score of field reports about digs where children’s toys, games, and material culture would have been expected to be found. And yet not one game or marble was reported!

Astonishing!

How many marbles did Stolk dig? She found 373 marbles! She dug 170 miniatures and both round and square gaming pieces and tokens were the next high find at 29. Remember, we are talking about marbles which date from 1600 – 1800! And Stolk dug only some 48 known pits and there are about 100 pits in all!

A Whole Lot of Diggin’ Going On! Willemsen’s Finds

Annemarieke Willemsen is a Medieval specialist. She studied both art history and archaeology at Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. She received her PhD at Radboud in 1998. Her dissertation focused on late medieval children’s toys. Since 1999, she has been working at the National Museum of Antiquities as Curator of the medieval collections. There, she is responsible for all domestic finds from after the Roman period. She is particularly interested in material culture (also as a phenomenon) and everyday life in the Middle Ages, with an emphasis on children, play, education and fashion in the past.

In her paper “Medieval Toys”[12] Willemsen writes that “so far more than 1,200 toys have been recovered in the Netherlands and Flanders [Belgium] from the period from approximately 1000 to 1550. Similar children’s toys from this period have also been excavated in surrounding countries such as Germany, France, England and Scandinavia [Norway and Sweden].”

In her “Medieval Toys” paper, Willemsen notes that there are about forty different types of toys found from the period 1000 to 1550 and she briefly outlines eight of these. Unfortunately, marbles is not outlined, it is included among the forty types.

Some of the toys which medieval children played with: balls, bubbles, blocks, diabolo, animals, whistles, sleds, masks, rattles, nut mills, drums, kites, carts, and marbles!

Langley & Litster & Prehistoric Marbles

Finally, let’s look back at Langley and Litster[13] who told us about children’s toys often being categorized as ritual objects when found in field digs. They write:

“Certainly, many of the objects and features created during play can be expected to survive in the archaeological record surely we cannot uphold the notion that of the thousands upon thousands of prehistoric children to walk the landscape, they never played with anything but archaeologically fragile or archaeologically invisible items” (page 617).

Material playthings of children specifically mentioned in the hunter-gatherer ethnographies included … “other game materials: balls (being made of grass, hair, moss, possum skin, sealskin); bark targets; bones (knuckles; ring-and-pin game);cuttlefish; discs; drawing sticks; grass hoops; human bone; knuckle bones; leaves; marbles (seed/shell/stone/wood); playing sticks; shells; skipping rope; spinning tops; stick-dice; stones; string” (page 618).

Of course, we were delighted to see marbles included in the list! Two types of marbles stand out: shell and wood. Something else you don’t see every day is “human bone” fashioned or used as playthings!

On the other hand, we were familiar with children using nuts, berries, and Australian quandong as marbles. See our Post “Marbles from Mother Nature” @ https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/marbles-from-mother-nature-2/

Invisible Marbles & Toys in Museums

Since children were practically invisible in the archaeological record for at least the last 60 – 80 years, it stands to reason that children’s material culture, to include toys, games, and marbles, were not passed along to Museums worldwide for accession, curation, possible restoration, and then display and explanation.

We have written such explanations for children’s displays in museum and it is not easy! The display notes, which are read by visitors of all ages to the museums, need to be short but certainly more than a description of the artifact or cluster of artifacts. The display notes need to convey to visitors (which include children) how these children’s artifacts both fit into the overall collections and the contributions which they, and the children who played with them, made to their households and to the larger society.

Sometimes prehistoric and historic marbles do end up in museums. For example, these three marbles from Hollinger’s Island, Alabama, are curated and displayed at the Colonial Fort Condé in Mobile, Alabama[14]. However, these marbles were not discovered on an archaeological dig: they were discovered by a gentleman landscaping his yard in 1956! You can read all about the find in Chapter 4, “Pensacola—Canicas para Oficiales Militares” in The Secret Life of Marbles pages 86 – 90.

These three historic marbles were almost certainly mortuary offerings. They demonstrate that archaeologists are not the only ones who contribute to museums. We know that some remarkable donations are made daily to museums and other institutions. Some of these donations are well documented by the owners and they are added to the museum holdings.

But over the decades thousands of artifacts have been dug all over the world from Ulaanbaatar to Montgomery which should have been attributed to children but were not. Sometimes, like when a miniature bow and arrow is unearthed, they are added to the museum but as an adult tool to teach children key skills needed by the overall group rather than simply as a play thing. Again, the entire dig is filtered through an adult lens.

Look Again

Take another look at the photograph of the three Hollinger Island marbles. Now imagine you are in charge of an archaeological dig focused on adult graves and you and your team have found many grave goods: weapons, tools, beads and other jewelry, biofacts (mostly foodstuff), lead shot, and brick spalls. And these three clay or stone balls.

Your first guess might be that they are cooking balls and that they are associative with the food stuff. No, the size is wrong for cooking balls and the balls are much too worked for stones which are used and then often discarded.

Or maybe they are munitions and are associative with the lead shot and gun spalls (but no sign of a musket). But wait: these are all grave goods: things of importance to the individual in the grave. So, these stone and clay balls must be part of a ritual which the individual participated in. But you simply cannot be certain what they are and how they were used. They are simply too elusive.

Now What?

Now what do you do with them? How can you transfer them to the museum without any description except when and where they were dug?

We have personal knowledge as well as corroborative information from the literature that children’s toys and other artifacts were dug in the field, but not then sent to museums. Where exactly did these thousands of artifacts go? Storerooms, repositories without displays, museum archives, or university archaeology labs as teaching tools? We really would love to know.

Brookshaw

Sharon Brookshaw addresses this issue.

“Little consideration has been given to the material culture of children and childhood in the literature, and it remains a sparsely populated field of work. There have been texts written on childhood objects themselves, particularly histories and collector’s guides …but these have mostly been limited to toys, dolls and costume.

Few works have gone further to consider the relationship between these objects and children as a serious area of study. In archaeology, an area that might be expected to take an interest in investigating the material traces of children, they have been much neglected, perhaps because, in the more distant past in particular, children are perceived as intangible …. While the archaeology of children is currently going through a period of high interest .., up until relatively recently it was considered that ‘the child’s world has been left out of archaeological research’ …. Museum collections are a fundamental resource for material evidence …and, despite the idiosyncrasy of their assemblage, present a unique and intriguing opportunity for examining objects related to children and childhood.”[15]

Griffin

While Griffin, the fictional scientist in H.G. Wells’ 1897 book The Invisible Man, discovered to his horror that his invisibility was irreversible, we don’t believe this is the case with our invisible children.

We celebrate the inclusion of children, games, and toys like marbles as critical to the understanding of any culture at any time in history. Children have been present throughout history in times of plenty and times of plague, in times of war and and of peace. They played with toys and games, they left material evidence behind, and they must be acknowledged.

The category of children needs to be more visible in material culture studies and in museums. Archaeology digs have been called “portals to the past”[16]. In that case, museums which display artifacts from the digs, to include children’s marbles, are windows to the future.

References

- Jan Turek uses the phrase “Invisible Children” as her first sidebar heading in “Children in the burial rites of complex societies. Readings in gender identities,” page 75. In Paulina Ramonowicz, Ed. Child and Childhood in the Light of Archaeology. Chromcon, Wroclaw, Poland, 2013. PDF @ https://www.academia.edu/4128924/Child_and_Childhood_in_the_Light_of_Archaeology_ed_P_Romanowicz_Wroc%C5%82aw_2013?email_work_card=view-paper 12/29/2023 ↑

- Jeff Carskadden, Jeff & Richard Gartley. “A preliminary seriation of 19th-century decorated porcelain marbles.” Historical Archaeology, 24.2 (June 1990), pages 55 – 69. ↑

- https://www.academia.edu/about 12/29/2023 ↑

- Joanna Dąbal, “Ceramic children-related objects. Introductory remarks on post-medieval and modern urban and social background of children.” In Lech Cerniak, Ed. Gadańsk Archaeological Studies. No. 6, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology University of Gadańsk, Poland, University of Gadańsk, 2016, pages 135 – 157. ↑

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/stratigraphy-archaeology 12/31/2023 ↑

- @ https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/why-ancient-toys-are-elusive-artifacts 12/30/2023 ↑

- “Is It Ritual? Or Is It Children? Distinguishing Consequences of Play from Ritual Actions in the Prehistoric Archaeological Record” by Michelle C. Langley and Mirani Litster Current Anthropology, Volume 59, Number 5, October 2018. @ https://www.academia.edu/37405301/Is_It_Ritual_Or_Is_It_Children_Distinguishing_Consequences_of_Play_from_Ritual_Actions_in_the_Prehistoric_Archaeological_Record/ 12/25/2023 ↑

- While not scientific, “wonky” is a descriptive term that we heard over and over on archaeology digs and in the laboratory. ↑

- William Louis Calver and Reginald Pelham Bolton, “Children’s Toys Found in Revolutionary Camps,” History Written with Pick and Shovel. NY: New York Historical Society, 1950, pages 236 – 239. ↑

- “The sieve or sifter is a wire mesh screen used to strain or separate small pieces or artifacts from loose soil. Prior to the 19 century, screening was not widely practiced. Screens were mostly coarse-mesh screens used to recover coins and beads. Today, archeologists use several grades of mesh screen to sift through the loose soil at a dig. By using a sifter, the archeologist will find the smaller pieces of broken artifacts that otherwise might be missed.” @ https://classroom.synonym.com/archaeological-sifting-tools-12083865.html (12/31/2023) We both really enjoy sieving. We found that in Spanish sites such as Santa Rosa Island in Escambia County, Florida, an untold number of beads were discovered which would have been lost without sieving. We are not, however, as excited by wet sieving which is necessary with certain types of soil: Wet sieving is the “process of recovering finds and ecofacts from excavated archaeological deposits by passing them through one or more screens or sieves either suspended in water or washed through with running water, in some cases under pressure. The water acts to break down the finer sediments, removing them from the larger clasts [gravel, grit, sand] and objects that are left on the sieve.” https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803121929643 (12/31/2023) An ecofact or biofact is flora or fauna remains. For example, in Northern Florida we found hundreds of otoliths or earstones. Bony fish need otoliths to hear, navigate, and for balance. And depending on size they can tell scientists a great deal about what the people at a site ate. ↑

- Stolk, M. (2022). The archaeology of Vlooienburg Materiality and daily life in multicultural Amsterdam, 1600 – 1800. [Thesis, full internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam]. ↑

- “Medieval toys” is archived by Academia.edu @ https://www.academia.edu/ (1/1/2024). It can be accessed in PDF format by searching for Middeleeuws speelgoed. Also at academia.edu you may want to check Sophie Oosterwijk “ “The Medieval Child An Unknown Phenomenon?” Previously listed at http://www.the-orb.net/non_spec/missteps/ch6.html; subsequently published in S.J. Harris en B. Grigsby (ed.), Misconceptions about the Middle Ages (New York/Londen: Routledge, 2008), 230-235. (1/4/2024) We have been studying the absence of children in archaeology and Oosterwijk considers the supposed indifference which Medieval parents showed toward their children. By inference Medieval society had little regard for children.↑

- “Is It Ritual? Or Is It Children? Distinguishing Consequences of Play from Ritual Actions in the Prehistoric Archaeological Record” by Michelle C. Langley and Mirani Litster Current Anthropology, Volume 59, Number 5, October 2018. @ https://www.academia.edu/37405301/Is_It_Ritual_Or_Is_It_Children_Distinguishing_Consequences_of_Play_from_Ritual_Actions_in_the_Prehistoric_Archaeological_Record/ 12/25/2023 ↑

- PastPerfect Photograph and information provided by Nick Beeson, Curator of Collections, History Museum of Mobile, Alabama. Telephone and email communications on 7 and 11 January 2021. ↑

- Brookshaw, Sharon. “The Material Culture of Children and Childhood Understanding Childhood Objects in the Museum Context” Journal of Material Culture 14 (3) page 370. PDF “04 Brookshaw 106425 17/6/09….” PDF @ https://www.academia.edu/5046615/The_Material_Culture_of_Children_and_Childhood_Understanding_Childhood_Objects_in_the_Museum_Context?email_work_card=view-paper 12/25/2023 ↑

- “Excavation and Mapping” @ Portal to the Past http://portaltothepast.newsouthassoc.com/sample-page/excavation-and-mapping/ 1/2/2024↑