The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue NY The Cesnola Collection,

Purchased by Subscription, 1874 – 1876 #74.51.328

This gorgeous glass marble was probably found by Luigi Palma di Cesnola in Cypress between 1865 – 1876. It dates to the Imperial Roman period 1st – 4th CE. It is considerably older than either the Greiner or Leighton and Navarre Types of marbles[1]!

While we can’t be sure how it was made, it was probably mouth blown. The Museum’s description of it is fascinating: “translucent turquoise greenish blue; solid sphere; numerous small crescent-shaped impressions in the surface, combined with a few circles and possible letters; intact, but with interior cracks; dulling and pitting, with areas of brilliant iridescent weathering.”

The marble was positioned in the photograph so that some of the impressions, circles, and possibly writing are clearly distinguished.

Since it is Roman, it is natron glass which is a type of soda glass rather than glass made with plant ash. This type of soda glass was made using natron, a mineral, as a flux. Still, it is badly weathered or decayed[2].

In Chapter One, “Where Do Marbles Come From and Why?” in our book The Secret Life of Marbles Their History and Mystery, we reference Dr. Ian Ross Thomas[3], Curator of Greece and Rome at the British Museum, London. He believes that, like today, Roman glass marbles may have been made from recycled, or old, glass (page 8).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue NY, Glass hexagonal amphoriskos,

Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1881, 81.10.224

Comparing The Marble To Other 1st half of 1st century CE Glass

The photo above is an amphoriskos —a small type of amphora—which is a two-handled jar typically used by the ancient Greeks and Romans for storing and transporting liquids like oil. These little vessels were also often used for holding precious oils, perfumes, or cosmetics. In other words, it is an ancient perfume bottle.

This little jar or bottle was the type used in daily life which, if broken, could then be used to make marbles. The Met tells us that the jar is translucent cobalt blue with handles in the same color.Roman & Cypriot Glass

Certainly, glass which was broken around the house was not the only source of culllet for the Roman Cypriots. In the comprehensive story “Roman Cyprus[4]” we read the following:

“Before the invention of glass blowing in the mid first-century BC, glass had been a fairly rare and expensive luxury commodity, the use of which was mostly confined to containers for perfume and cosmetics. However, with the invention of glass blowing, glass became much more widely available and affordable and began to be produced on a much larger scale with factories dedicated to the production of glass being established throughout the Roman world, including Cyprus. Though it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between locally produced Cypriot glass and imported glass in Cyprus, it can be conclusively stated that glass was in fact being manufactured locally within the island.”

Alexis Drakopoulos[5], the author of “The Evolution of Cypriot Burials over Time” which is cited below, told us by email that while the marble may well have been made in Cyprus, “It’s definitely not something prototypical of Cypriot culture.” After all the time and energy that we have poured into researching this marble and Cypriot glass, we would absolutely underscore Drakopoulos’ observation.

Again, we can’t be positive, but if it is difficult to tell the difference between Cypriot and Roman glass. Like Rome, the Cypriots must have been using soda glass with natron flux by the 1st Century AD.

“A glass workshop was discovered at Tamassos …. It is likely that they dated to the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD. Blocks of glass were discovered at Salamis which seems to indicate that this was another glass production center though a furnace associated with this site has not yet been discovered. Cypriot glass is thought to have flourished…from 140 AD to 240 AD and … most of the glass discovered is dated to this time. The fact that the economy in Cyprus was flourishing during this period further supports this conclusion.” Emphasis Added.

Evidently, these blocks of glass were used as cullet. We do not see in this pullout where the colorant for the glass was obtained. And we see no reference to glass marbles. But wouldn’t it be wonderful to discover a glass marble factory on Cyprus?

“Roman Cyprus” continues that large quantities of glass found in the tombs of Limassol and Amathus. Glass from the tombs has taught us that there was a fair amount of homogeneity in Cypriot glass is fairly homogeneous and that its function was for the most part limited to daily use, being employed either toward cosmetic purposes or as tableware.

The Met’s 1914 Handbook of the Cesnola Collection of Antiquities from Cyprus has a very short entry named “Other Objects of Plain Glass, Clear or Colored”[6] and the list contains these astonishing artifacts (page 513):

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue NY The Cesnola Collection,

Purchased by Subscription, 1874 – 1876 74.51.337

Glass Spindle-whorls.

This photograph from the Met notes that the whorls had a domed-body, and a flat bottom with circular grooves. They had a vertical hole which was larger on bottom than on the top.

When recovered intact the whorls have pinprick bubbles, dulling and pitting, and iridescence like the marble at the top of this story. Whorls were made by winding a glass thread in a spiral around a rod.

Spindle whorls were used to weight spindles when hand-spinning yarn. They were made in a variety of materials including glass, stone, ceramic fragments and fired clay[7].

Bracelets.

Sometimes these were decorated with multiple or twisted threads of glass.

Dipping rods

A spoon

Made of clear glass with a pointed bowl and long handle.

Pins and a needle.

And a number of small artifacts like a many-sided bead, knobs, and a tube.

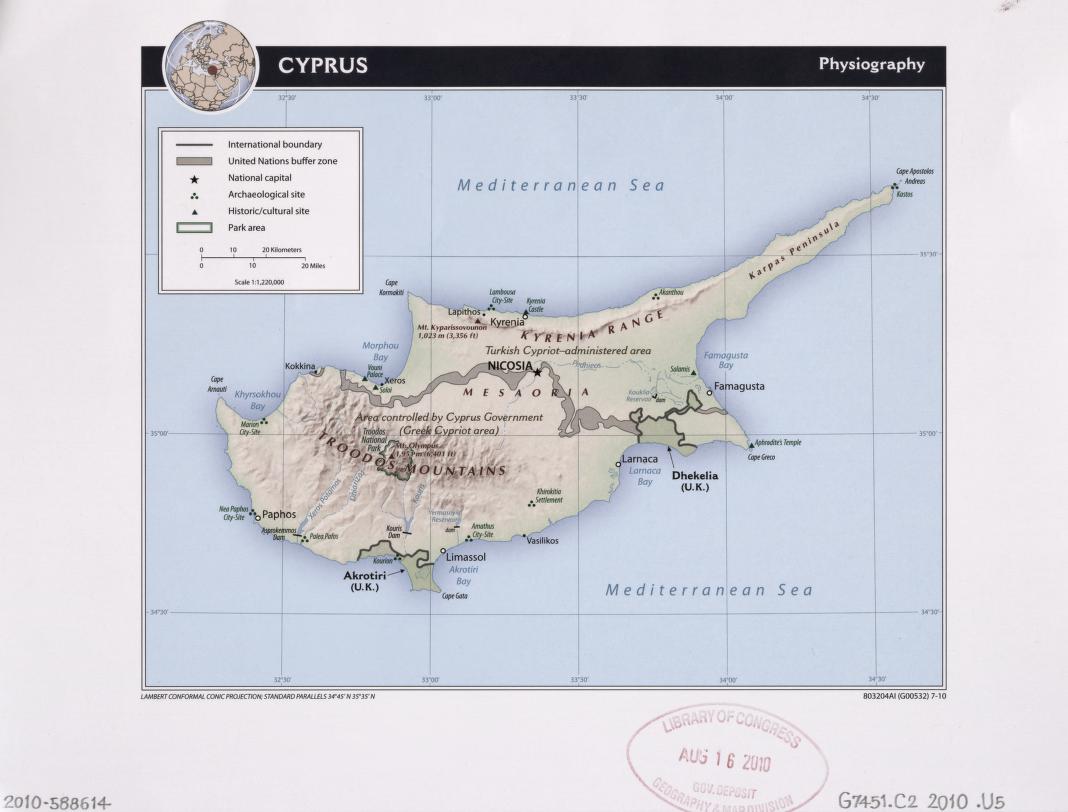

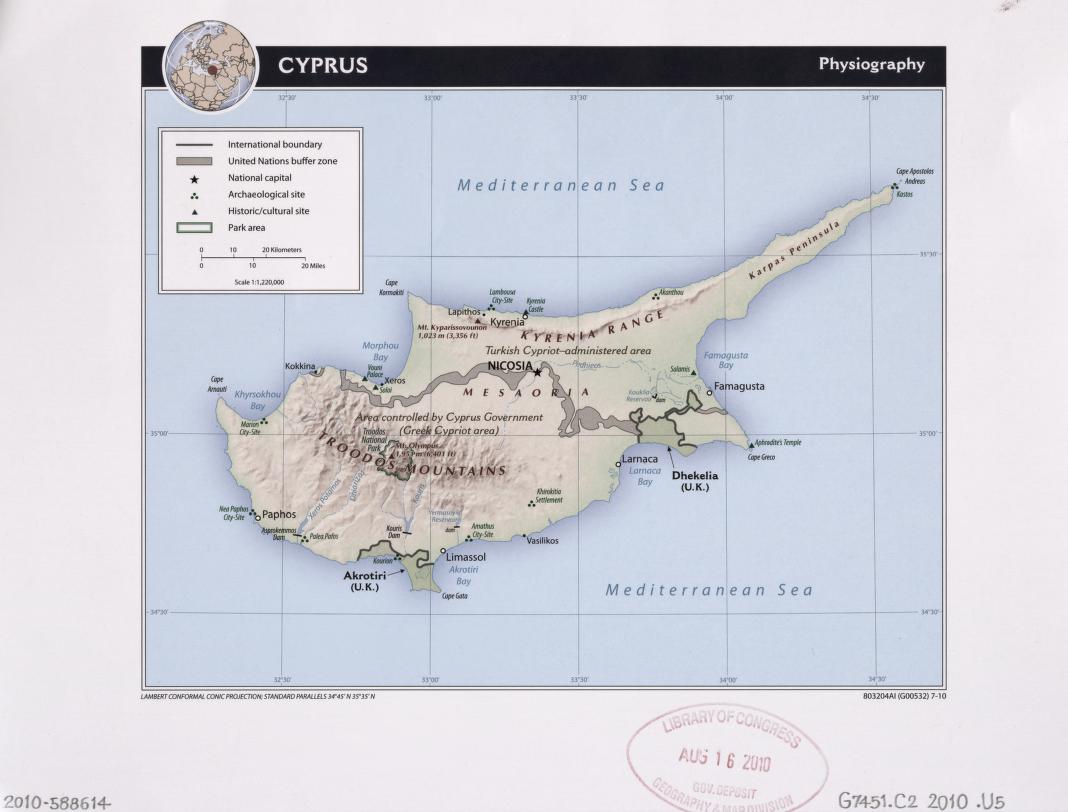

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division[8]

Locations On The Map

Now that we know that the Cypriots and Romans did make objects out of glass in the 1st century AD and that there were “glass towns” on the island, we want to pinpoint a few of these towns and villages. Hopefully, this will give you a general orientation to the island. When we discuss the travels of the man who found the artifacts in the Cesnola Collections, to include the marble, you can refer back to the map to see where he was.

This map is a bit hard to read, but we will attempt to point out a few “glass towns” of ancient Cyprus. First, Tamassos is not shown. However, Nicosia is. It is the capital and largest city in Nicosia District and it is in the Turkish-Cypriot administered area. Nicosia lies in the center of the island and just north of the “dividing line” (called a Green Line) in Cyprus. Today south of the Line is the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus; to the north is The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) which is recognized only by Turkey.

You might want to compare this modern map with the one di Cesnola, who found the artifacts, provides in his book Cyprus: Its Ancient Cities, Tombs And Temples. While the map does not have a page number, it is just past the table of contents.

The ancient site of Tamossos, where a glass workshop has been discovered, is only 13 miles southwest of Nicosia and in the same political district of Nicosia. The site is near to Politiko, Pera, and Episkopeio towns and villages.

The blocks of glass, which we believe were used as cullet, were found at Salamis[9]. Salamis is on the map, but it may be a bit hard to see. It is on Famagusta Bay. The name is in green ink and it is designated with a green triangle because it is designated an Historical/Cultural site. The site is about four miles from the modern city of Famagusta.

Famagusta[10] is an ancient port city and it gave the merchants and glass-makers easy access to the Mediterranean Sea and established trade routes. And, as noted above, Salamis glass could be shipped to other ports in ancient Cyprus for their own use and for distribution to other glass towns.

Limassol, also known as Lemesos, is a city on the southern coast of Cyprus and capital of the Limassol district. We enjoyed two wonderful vacations in Limassol.

Amathus or Amathous is also on the southern coast and it is some seven miles to the northeast along the coast from Limassol. At one time it was a royal city of Cyprus. It is noted as a cult sanctuary of Aphrodite.

Pafos Archaeological Park (UNESCO) is a designated archaeological site. Pafos is about half-way up the southwest coast of Cyprus in Kato Pafos and near to the Harbor. We had an unforgettable experience in Pafos, both in town and in the Park, where we spent a good deal of time in the Tombs of the Kings.

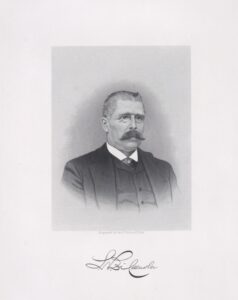

An Introduction To Luigi Palma di Cesnola[11]

An Introduction To Luigi Palma di Cesnola[11]

In our story “In The Shadows of The Tomb…” we introduced Charles Masson who explored in Afghanistan in the 1830s – 1840s. Masson was an antiquarian who worked so early in the development of the science of archaeology that at least some of his methods and notes are understandable.

On the other hand, di Cesnola, for whom the collection of Cypriot artifacts at the Met is named, explored in Cyprus in the 1860s – 1870s. By this time the rudiments of scientific archaeology were understood and were in practice. Fundamental precepts of this understanding were: site determination, management, and comprehensive notation of each artifact recovered, where in situ it was discovered, and so on.

While di Cesnola claimed to have studied at the British Museum, he was as unschooled as Masson and, if possible, more aggressive in his searches and less prone to note his finds properly.

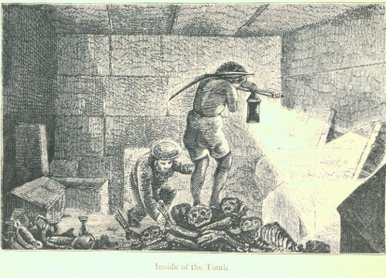

This is an image of a “dig” which di Cesnola provides on page 272 of his book Cyprus: Its Ancient Cities, Tombs And Temples.[12] Di Cesnola remains a controversial figure to this day. He has been called both an “avid archaeologist” who discovered some 35,000 artifacts, “audacious and high-handed,” an amateur archaeologist, and a treasure hunter[13]

Di Cesnola Was A Soldier

Luigi Palma Di Cesnola was born in July 1832 in Rivarolo Canavese the second son of a count in the Kingdom of Sardinia which is now in Italy. The Kingdom was on the island of Sardinia and its capital was moved to Turin. As the second son, di Cesnola had no title.

At age 17 (La Gazzetta Italiana claims it was 15) di Cesnola joined the Army and fought in the First Italian War of Independence. Like Charles Masson, di Cesnola was a good soldier who was promoted to second lieutenant and decorated for bravery. However, at just 20 years old he was dismissed from the Army. No one is certain why he was discharged and the topic is controversial to this day.

Next di Cesnola served as aide-de-camp to General Enrico with the British Army in Crimea. He moved to the United States in 1860, served in the Federal Army during the Civil War and was captured by the Confederates and stayed in Libby Prison until 1864 when he was released in a prisoner exchange.

Medal Of Honor

Di Cesnola’s Civil War experiences read like a dime-store novel but they are all true! Remember how he was discharged from the Italian Army? Well now he protested, a bit too loudly and a bit too much, about the promotion of a less experienced officer in his regiment. He was arrested and stripped of both his saber and sidearm.

Then it happened at Aldie in Loudoun County, Virginia in June 1863. Aldie was part of the Gettysburg Campaign.[14] The battle lasted about four hours and while often fierce it was inconclusive.

In the heat of battle di Cesnola did something both courageous and insane! The Medal of Honor Society tells us what happened:

Luigi Palma di Cesnola was awarded the U.S. Medal of Honor for his bravery during the Battle of Aldie on June 17, 1863, during the American Civil War. Despite being under arrest at the time, he saw his regiment falling back and took action without his arms. He rallied his men, accompanied them in a second charge, and continued leading them until he was desperately wounded and taken prisoner.[15] Emphasis Added

Yes, he was awarded the Medal of Honor by his adopted country! Not only was he imprisoned and badly wounded, he was sent to Libby Prison in Richmond. “Libby Prison was a notorious Confederate prison ….[which held Union Army officers]. The conditions were notoriously harsh, with overcrowding, poor sanitation, and severe food shortages leading to high mortality rates.”[16] He was released in early 1864 in a prisoner exchange.

The Job Of His Lifetime: US Consul to Cyprus

Things just keep getting curiouser and curiouser[17]. To our knowledge di Cesnola had never been in Cyprus. And we have no idea why he suddenly wanted to help American citizens on the Island, nor if he had any ideas about trade and cultural exchange with Cyprus, or visa processing. But on March 13th 1865 he was appointed US Consul by President Abraham Lincoln.

As Imagined by Microsoft Copilot

From what we have read in his 1878 book Cyprus Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, & Temples, in which he evidently promotes himself to General[18], it is incredible to us that he was ever in the Office in Tuzla (Larnaca)! However, he served from 1865 – 1877. He even served as Russian Consul for a time, but that was evidently because he needed certain dig permits which he could not get as US Consul.

‘Diggin’ Down & Fixin’ Up

Di Cesnola dug holes in tombs all over Cyprus from stem to stern — from Famagusta to Paphos. And, as we noted above, he removed some 35,000 artifacts from the Island. You can see hundreds of these artifacts at the Met[19].

If you read our story “In The Shadow of The Tomb” featuring Charles Masson then you know that Masson, too, collected thousands of artifacts in Afghanistan. However, Masson collected thousands of small coins.

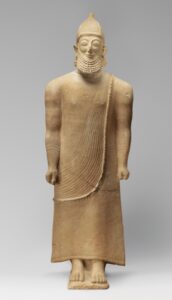

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue NY The Cesnola Collection,

Purchased by Subscription, 1874 – 1876 # 74.51.2460

Di Cesnola, on the other hand, collected almost anything in the tomb! His critics would say that he was interested in anything which he thought that he could sell —either to museums in Europe or America or to private collectors[20].

This limestone statue from the last quarter of the 6th century BCE, for example, is just over six feet tall! Some statues were even taller and they weighed over 1,100 pounds!

This statue tells us something else about de Cesnola’s collections. The Met writes: “It is possible that the head and body did not originally belong to the same work. The articulation of each part, however, testifies to the first influences of Greek sculpture on that of Cyprus.” We have no idea who modified or “fixed” some of the artifacts, nor how many were repaired, but it did happen in Cyprus. And considering di Cesnola’s lackadaisical attitude about digging in the tombs, we have a pretty good idea who “fixed” them and why.

What Did The Digger Think About His Diggins’?

We have a good idea by now of how di Cesnola operated. He rode horseback from place to place, by the Mediterranean Sea, in the mountains, which are often breathtaking, and across the plain. He searched for gravesites and we are sure he spent some time talking to locals about where historical sites existed.

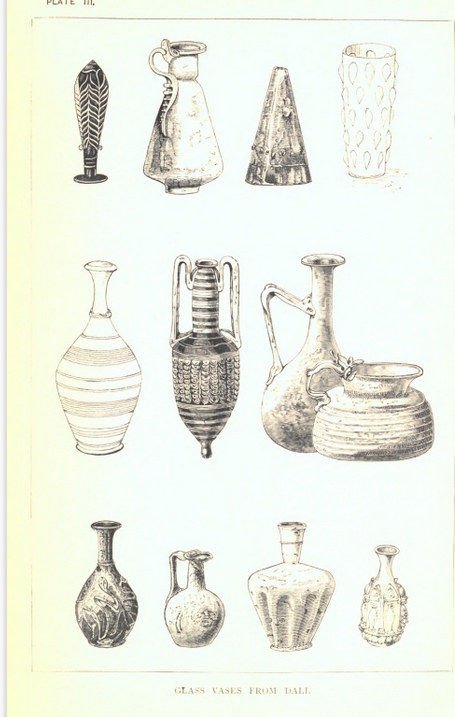

Cyprus Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, & Temples page 73. Examples of glassware dug by di Cesnola.

Look closely at some of the handles as well as the wide variety of styles and forms

In the “Preface” of Cyprus Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, & Temples,

he explains why he wrote the book He wrote the book, “to some extent,” because it

“…was imposed upon me as a duty, by the fact that several distinguished scholars had expressed their fears as to whether my excavations had been conducted in a systematic manner, whether the ruins had been left in a suitable condition for future study and investigation, and whether such a journal of the discoveries had been kept as would, from its details of how and where all the most important monuments had been found, prove of interest to science.”

So, it is clear that de Cesnola was very aware that archaeology was changing from a casual amateur affair to a more formal and rigorous science.[21]

In the Preface he also explains that his digs “…were perhaps not conducted in all their details according to the usual manner adopted and advocated by most archaeologists, I am unwilling to dispute, but there were many serious considerations which I was not at liberty to disregard.”

He then lists several of these considerations: the terms of his firman (decree, order, license, etc.) given to him by the Ottoman Government in Cyprus; he had no funding except from his own pocket; he knew that even if he had restored the tombs to their original condition when he finished, then the local peoples would destroy them carrying away the stones for their own use; and, finally, he had little help, organized staff, nor assistants.

He doesn’t mention that he received a salary for his consular work by the Department of State. In the 19th century consular officers could also rely on fees for services which they provided such as visas, notarizing documents, and other administrative tasks. Of course such work would require de Cesnola to be in his office in Larnaca[22]. And we can find no mention of what he thought about patching up rattly old artifacts!

What Did The Ottoman Government Think of di Cesnola?

We will give up you paragraph about what the Turkish Government thought of di Cesnola:[23]

“…the Muslim judge wrote to the governor, stating that unless the excavations were stopped immediately, all the fields would be ruined and be unproductive, and the government would not be able to obtain its revenue. Moreover, in fact, the ruler of Dali imprisoned excavation staff when he saw that the baskets they had in their hands contained human skulls removed from graves. However, Cesnola was able to ensure they were freed, meeting with the Governor, Said Pasha, and explaining that the graves which had been opened did not belong to Muslims but to a period long before Islam.”

Evidently, di Cesnola believed that grave robbing was perfectly all right as long as the dead were not Muslim! To see more excerpts about di Cesnola’s amazing exploits on the Island, see the Addendum at the end of this story.

Dali (or Dhali), who is mentioned in this excerpt, is a town in Cyprus, located southeast of the capital city, Nicosia. It’s close to the ancient city of Idalion, which was known for its copper trade in ancient times.

The Met & The Cesnola Collection

We simply cannot summarize the relationship of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York better than the abstract in the story “The Mainstream Media and the ‘Shocking Bad Art’ from Cyprus: 1870s New York Reacts to the Cesnola Collections”[24]:

“When the [MET] first opened the doors of its Fifth Avenue building on March 30, 1880, the majority of the exhibition space was occupied by Cypriot art purchased by the Met’s trustees from … di Cesnola in two lots, one in 1872 and another in 1876. The two collections amounted to around twenty thousand objects, all finds Cesnola had acquired while serving as US Consul on the island from 1865–1876. After the acquisition of the second collection, Cesnola left Cyprus to become the first director of the Metropolitan Museum, a position he held until his death in 1904. New Yorkers in the 1870s were most intrigued by the works of limestone sculptures from the sanctuary at Golgoi. In the 1880s these objects would become embroiled in a scandal because of the claim that Cesnola had performed intentionally misleading restorations, but before that disgrace and through much of the 1870s, New Yorkers were processing the arrival of an enormous volume of ancient Cypriot objects in a relatively short amount of time.” Emphasis Added

We believe that the Met trustees had to have at least some knowledge of how di Cesnola came into possession of the artifacts. It was hardly a secret in the art and academic world at the time. Cemil Çelík tells us that during his eleven years on the island di Cesnola “… unearthed 15 temples, 6 aqueducts, 65 necropolises and 60,913 graves throughout the island.” (page 283).

Aphrodite

The excerpt above mentions “the sanctuary at Golgoi.” When di Cesnola was on Cyprus, there were two temples at Golgoi which is an ancient city known for its worship of Aphrodite. If you can find Famagusta on the map, then run your finger along the southeastern coast to that point sticking out in the Mediterranean Sea. That is Cape Greco and Aphrodite’s temple is out on the point. Di Cesnola took 1,000 artifacts from the temples alone![25]Needless to say, New Yorkers in the 1880s knew all about Aphrodite. After all, she was the Greek goddess of love, beauty, desire, and all aspects of sexuality[26]. You can imagine the type statues the people expected to see from her temples! At the very least they expected to see Greek or statues heavily influenced by the Greek culture.

Reaction Of The Met & New Yorkers To The Artifacts

In spite of a media flurry about the opening of the Met and the di Cesnola collection, New Yorkers either visited once and failed to recommend the Collection to others or simply stayed away entirely. Attendance was poor.

W.J. Stillman, a well-known journalist and art writer at the time, wrote and delivered an infamous report to The Council and members of the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society of New York or simply to the Met.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue NY The Cesnola Collection,

Purchased by Subscription, 1874 – 1876 #74.51.328

Stillman’s main points are “…a deplorable recklessness of attribution as to the localities of discovery… evident repairs and alterations in certain pieces …which makes it impossible to decide whether they have, or have not, undergone similar alterations … and by attributions which assign an important part of the Collection to a single deposit, although the evidence … points indisputably to the non-existence of the supposed deposit.” [27] Needless to say, Stillman’s report was scathing.

Other Roman Marbles

© The Trustees of the British Museum.[28]

Somehow the Roman glass marble in this story survived the uproar and the Met kept it with the Collection. Perhaps one reason it was retained, and apparently without controversy, is because Roman marbles had been found before. For example, these glass, clay, and stone Roman marbles were dug in Egypt by the Egypt Exploration Fund, which is well respected and which has always had a reputation for strict archaeological principles.

Wrap Up

There is no way to close out the Roman Marble and di Cesnola story short of just stopping. We haven’t even mentioned Luigi’s brother Major Alexander Cesnola. We have no idea which Army he served, but he did serve as vice-Consul to di Cesnola while his brother was away on artifact business. He only served six months until the American Government abolished the Consular office along with about 120 others due to economic reasons. Alexander was as enthusiastic as Luigi about digging across Cyprus, and he was just as “disciplined” an archaeologist. We do have a bit more about him in the Addendum.

Luigi Palma Di Cesnola returned to the United States in 1879 and he became the first Director of the Met. He continued in that position until his death in 1904. We have noted the criticisms of di Cesnola made by W.J. Stillman. Stillman was certainly not alone.

Clarence Chatham Cook was a 19th-century American author and art critic. He wrote a series of articles about American art for The New York Tribune between 1863 and 1869. He became a forceful and effective critic of di Cesnola’s Collections. But through it all di Cesnola served the Museum and he worked hard over the years of his tenure to expand the Museum’s collection and to repair its tattered reputation.

And somehow the ancient Roman glass marble survived and remained in the Collections of the Museum. When we wrote about Charles Masson in the story “In The Shadows of The Tomb”, we marveled that small glass marbles could ever survive being found in tombs in Afghanistan, transported to Great Britain, and still be tucked away in the Museum archives.

If possible, we are even more astounded that de Cesnola even picked the marble up! Remember, he wanted big things that he could sale and make big money on and he did not really care who the buyer may be. And he was interested in stone rather than glass. On top of all that, at least one of his artifact shipments, with about 5,000 objects, sank!

Archaeologists have acknowledged the importance of glass to the culture, economy, and utility of societies since at least the early 19th century. Carolyn Wilke, Knowable sums up the place of glass in scientific and academic study in “A Brief Scientific History of Glass”. [29] And as we note in this story di Cesnola did recover glass bracelets, vases, beads, bottles, and strapped and twisted amphorae. And at least one marble.

But none of this glass would bring di Cesnola much money; it took up little display room; and it could easily be overlooked by visitors to any Museum.

So, it is a wonder and a marvel that a Roman glass marble found its way into one of those baskets that the workers used to move objects (and skulls!) from the tombs. We cannot even imagine what the marble was doing in the tomb in the first place! Grave goods? And this Roman marble, and others, was a part of the much larger human history.

Marbles have been with us in one form or another since the Paleolithic era. And they have been part and parcel in war and in peace. In America they have been found among the Native American tribes and bands, in Colonial America, during the Manifest Destiny and the “wild west,” and throughout the Great Depression and the turbulent years of World War II internment of Japanese Americans. While marbles often receive short shrift by the academic and archaeological community, they have and still do tell a secret and critically important history.

Addendum

Di Cesnola’s adventures in Cyprus read like a Raiders of The Lost Ark movie, but he was all too real. W.J. Stillman does a wonderful job of telling us what the end result of eleven years of digging all across the Island, but it is remarkably hard to gain any insight from the other side: from the Ottomans whom he was tormenting. Cemil ÇELİK[30] gives us that insight and excerpts from his side are just too good to pass up. So, here are just a few clips.

“When Cesnola realized that attempts were being made to prevent his archaeological research and removing abroad the antiquities he collected, he looked for ways to quickly move them abroad.” The 1869 Statute brought prohibitions in this respect. However, despite the fact that sending antiquities abroad was illegal, he had obtained a license with which he was able to overcome the ban. PAGE 273 CEMIL

“Then he could not keep the collection in Cyprus any longer. He requested a ship from the American Fleet Command for its transport to America, and this request was met in a short time. He loaded the whole collection on the ship on his return to the island but received two telegrams reminding him that it was absolutely prohibited for him as the American consul, to take the antiquities out of the country. However, on the advice of Besbes, the consulate translator, he succeeded in removing the collection from Cyprus under his status as Russian consul.” PAGE 276 CEMIL Emphasis Added

“Cesnola sailed for New York on December 28, 1872, with 275 boxes of artefacts on five separate ships … Cesnola in the United States completed the procedures for the sale of the collection to the Metropolitan Museum and for its display …. Among the artefacts sold by Cesnola to the Metropolitan Museum in 1872 were more than 1700 pieces of glass artefacts, and he returned to Cyprus on September 30, 1873 ….” PAGE 278 CEMIL Emphasis added

Was the Roman glass marble a part of these 1700 artifacts? We think it was and we also think that it was accessioned as a “glass ball.” Who was minding the Consular Office for almost a year? And was the Government paying him for this self promotion?

“…In a letter sent by the American Embassy to the Vizier’s office on November 20, 1876, it was stated that the Republic of North America (meaning the United States) did not certify its consular officials in Cyprus, the consulate had been abolished, and consequently, Cesnola had been dismissed. In another letter sent by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs to the American Embassy, on January 15, 1877, it was stated Cesnola had failed to abide by the conditions of the permit to search for antiquities; he had avoided delivering part of the historical artefacts he had acquired to the Müze-i Hümayun, as was required. It requested action be taken to recover these. The American Embassy responded that as of November 20, 1876, the American Consulate in Cyprus had been abolished, so Cesnola no longer had any connection with the Embassy, and that they did not know where he was …. However, despite the fact that his license had been cancelled, Cesnola continued with his excavations in 1876 …. ” PAGE 282 CEMIL

And, finally, here is the assessment of his host, the Ottoman Empire, which on Cyprus was referred to as the Eyalet of Cyprus, of the Cesnolas:

“The American consul, General Palma di Cesnola and his brother, Alexander Cesnola, the deputy consul for Paphos, aimed to become rich and famous by setting off in search of antiquities on the island of Cyprus.” PAGE 286 CEMIL

References

- https://oldraremarbles.com/product-category/leighton/ 2/2/2025

- We discuss Roman glass and its influences on German glass production in detail in our story “The Lauschaer Glashütte & Origins of the Modern Glass Marble“ @ https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/modern-glass-marbles/ 2/2/2025 ↑

- Dr. Thomas died aged 44 after surgery. You can read about his accomplishments in his obituary @ https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/dec/18/ross-thomas-obituary 2/4/2025↑

- https://trellows.eu/roman-cyprus-cypriot-history/?form=MG0AV3 2/2/2025 ↑

- @ https://www.ancientcyprus.com/collections/alexis-drakopoulos 2/6/2025 ↑

- When the explorer Luigi Palma di Cesnola found this type glass in Cyprus he called it “hyaline” glass by which he meant a glassy, clear or colored transparent appearance. The Met Handbook: Myres, John L. Handbook of the Cesnola Collection of Antiquities from Cyprus. NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1914. You can see a digitized version @ http://www.archive.org/details/cesnolacollectionmetriala 2/5/2025 ↑

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1896-0411-103 2/6/2025 ↑

- United States Central Intelligence Agency. (2010) Cyprus, Physiography. [Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2010588614/

- See https://britonthemove.com/salamis-in-cyprus/?form=MG0AV3 2/4/2025 ↑

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Famagusta?form=MG0AV3 2/4/2025 ↑

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue NY Object Number #1976.620: Engraving after a photograph by George Edward Perine (American, South Orange, New Jersey 1837–1885 Brooklyn, New York), Title: Luigi Palma di Cesnola. ↑

- You can see a digitized version of the book @ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Cyprus_Its_Ancient_Cities_Tombs_and_Temp/ULWL5_wtowoC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PR3&printsec=frontcover 2/7/2025 ↑

- “Avid” by online newspaper La Gazzetta Italiana @ https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/user-login (2/7/2025) “Luigi Palma Di Cesnola”, “high-handed” by Elizabeth McFadden. The Glitter & The Gold: A spirited account of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s First Director, The Audacious and High-Handed Luigi Palma di Cesnola. NY: Dial Press, 1971, and treasure hunter in Ann-Marie Knoblauch ‘The Mainstrean Media and the ‘Shocking Bad Art’ from Cyprus.” Near Eastern Archaeology 82.2 (2019) page 67. ↑

- We were not familiar with the Battle at Aldie. If you aren’t either then you might want to check “Aldie,” American Battlefield Trust, @ https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/aldie?form=MG0AV3 (2/9/2025). We also recommend “The Battle of Aldie, 1863,” American History Central @ https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/battle-of-aldie/?form=MG0AV3 2/9/2025↑

- Medal of Honor Society @ https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/louis-p-di-cesnola?form=MG0AV3 ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libby_Prison?form=MG0AV3 & https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/libby-prison/?form=MG0AV3 1/7/2025 ↑

- With a nod to Lewis Caroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. ↑

- Louis Palma di Cesnola achieved the rank of Colonel in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War. Although he was nominated for the brevet rank of Brigadier General, the U.S. Senate never confirmed his appointment. So, he just overlooked one small detail! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Palma_di_Cesnola?form=MG0AV3 (2/11/2025) “It was documented and claimed by the prosecutor in a New York court in 1883 that Cesnola had never been officially appointed a General [by Congress] and that he, therefore, had been using the title of General unlawfully (Testimony of L. P.Di Cesnola, 1884:42). Cemil ÇELİK, “The American Consul Cesnola Brothers and The Fate of Antiquities in Ottoman Cyprus” Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, http://busbed.bingol.edu.tr, Yıl/Year: 11 • Sayı/Issue: 22 • Güz/Autumn 2021. ↑

- For example @ https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=di+Cesnola+collectio0n+Met 2/10/2025 ↑

- In his book Cyprus Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, & Temples (page 454) di Cesnola tells us that “Sales were also made of small collections to the Berlin Museum, the Cambridge Museum, the Kensington Museum, and the Boston Museum of Art.” We could not find his work in any of these museums. The Boston Museum of Art does have a handful of coins from Cyprus (roughly 1st century AD) but the attribution isn’t de Cesnola. He did donate some artifacts to museums in Egypt, Italy, and in the United States. ↑

- For just one example of a proper archaeological study see the MA Thesis The Archaeology of Gardens in Japanese American Incarceration Camps by Koji Harris Ozawa, San Francisco State University, May 2016 @ https://www.academia.edu/25565308/The_Archaeology_of_Gardens_in_Japanese_American_Incarceration_Camps?email_work_card=view-paper 2/11/2025 ↑

- https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history/congress?form=MG0AV3; &https://research.mysticseaport.org/item/l006405/l006405-c014/?form=MG0AV3; 2/11/2025 ↑

- Cemil ÇELİK, “The American Consul Cesnola Brothers and The Fate of Antiquities in Ottoman Cyprus”. Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, http://busbed.bingol.edu.tr, Yıl/Year: 11 • Sayı/Issue: 22 • Güz/Autumn 2021, p. 272 ↑

- We really recommend that you at least look over this very readable story @ https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/items/7d447312-93dd-46d3-8baa-9714970f03c3 1/30/2025 & https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/66cdee26-ed47-4b8e-bc60-29c3eae3b236/content 1/31/2025 ↑

- Cemil ÇELİK, “The American Consul Cesnola Brothers and The Fate of Antiquities in Ottoman Cyprus”. Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, http://busbed.bingol.edu.tr, Yıl/Year: 11 • Sayı/Issue: 22 • Güz/Autumn 2021. ↑

- Mark Cartwright, “Aphrodite” October 24, 2018 @ https://www.worldhistory.org/Aphrodite/?form=MG0AV3 2/12/2025 ↑

- W.J. Stillman. Report on The Cesnola Collection. Np: Privately Printed. See Stillman @ https://arthistorians.info/stillmanw?form=MG0AV3 1/31/2025 ↑

- Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Founded in 1882 by Amelia Edwards as the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) but later renamed the Egypt Exploration Society (EES). It has always maintained a high research and fieldwork profile in Egypt and publishes an annual journal, the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. The process by which the British Museum acquired objects from the EEF was as follows: the Museum paid a subscription to the EEF, on the explicit understanding that it would receive objects from the Fund’s excavations in return. Excavations were then carried out, and the finds which accrued to the EEF were subsequently distributed to the many institutions and individuals who had subscribed. ↑

- Smithsonian Magazine online @ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/a-brief-scientific-history-of-glass-180979117/?form=MG0AV3 2/15/2025 ↑

- Cemil ÇELİK, “The American Consul Cesnola Brothers and The Fate of Antiquities in Ottoman Cyprus”. Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, http://busbed.bingol.edu.tr, Yıl/Year: 11 • Sayı/Issue: 22 • Güz/Autumn 2021. ↑