Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress[1]

Ever heard of Amache? What about the Amache Internment Camp or the Granada Relocation Center in Granada, Colorado? No? Well let us tell you a story about courage, the resilience of children, the toughness of their families, lives turned upside down . . . and marbles!

Regardless of the researcher’s perspective, it is impossible to please everyone when writing about the terrible injustice of removing American citizens against their will from their homes and into barbed-wire camps. It is illegal to confiscate an American’s property, to forcefully move families from their homes and places of work and to confine them indefinitely. But all of this did happen during World War II.

In order to write effectively about this sensitive subject words must be used which some may consider inappropriate. And, needless to say, the language used to describe Japanese American citizens has changed dramatically since World War II.

The Japanese American Museum of Oregon offers a revised terminology to reflect the story. We studied this guide and others before we even started our research and we have made every attempt to be fair and sensitive in our reporting. On the other hand, we see no need to refer to the internment camps as concentration camps as the Museum claims is now a more effective term[2].

In the Immediate Aftermath of Pearl Harbor

Amache is but one of the Japanese Internment Camps established after the Imperial Japanese Navy attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The National Archives tell us that there ten camps in the United States: “’Relocation centers’ were situated many miles inland, often in remote and desolate locales. Sites included Tule Lake and Manzanar in California; Gila River and Poston in Arizona; Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas, Minidoka in Idaho; Topaz in Utah; Heart Mountain in Wyoming; and Granada in Colorado.” There was also a camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico.

Amache[3], in Prowers County and less than two miles from Granada, opened on August 24, 1942, and it was the smallest of the camps with 7,318 internees at its peak. It covered an area of some 10,500 acres. Still, Amache became the 10th largest community in Colorado at the time. The camp closed on October 15, 1945[4]. Some of the internees did not leave the camp until late January 1946.

Before World War II ended, over 120,000 Americans of Japanese Ancestry, both Issei and Nisei were incarcerated in these ten camps. About 80,000 of the internees were second-generation United States citizens (Nisei) while others were first-generation Japanese Americans, Issei, who had emigrated from Japan and were not eligible for United States citizenship[5].

On What Authority?

“One of the key players in the confusion following Pearl Harbor was Lt. General John L. DeWitt.”[6] DeWitt was born in Fort Sidney, Nebraska, in 1880 and when the War started he had served in the Army since 1898. He was a veteran of the Philippine Insurrection and the Mexican Punitive Expedition.[7]

“DeWitt had a history of prejudice against non-Caucasian Americans, even those already in the Army, and he was easily swayed by any rumor of sabotage or imminent Japanese invasion.”[8]

The Nation Park Service tells us that “on December 19, 1941, General DeWitt recommended ‘that action be initiated at the earliest practicable date to collect all alien subjects fourteen years of age and over, of enemy nations and remove them’ to the interior of the country and hold them ‘under restraint after removal’”

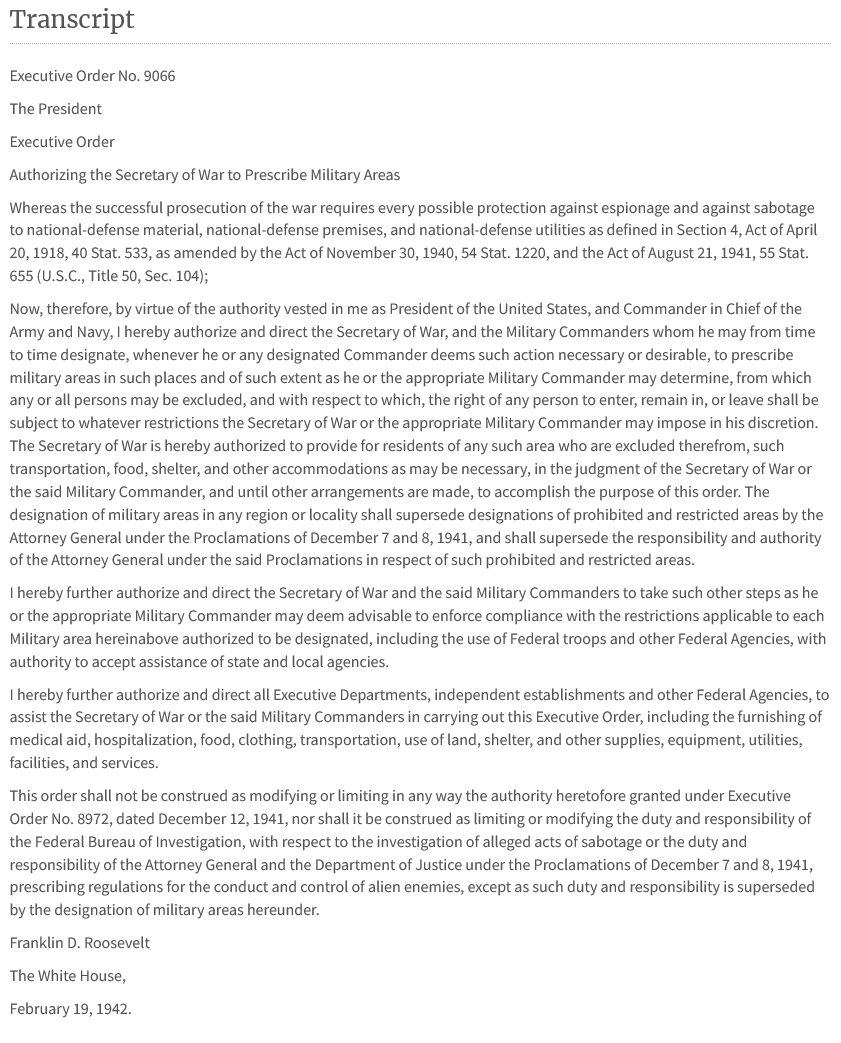

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which we include in its entirety at the end of this story. The Army was granted authority to create a military zone and then to remove all residents of Japanese ancestry. Japan was, by this time, an “enemy nation” as General DeWitt emphasizes. A civilian agency was created to care for the Japanese who were removed to camps in the interior of the country.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was thus created and it started work on March 18, 1942 by Executive Order 9102.

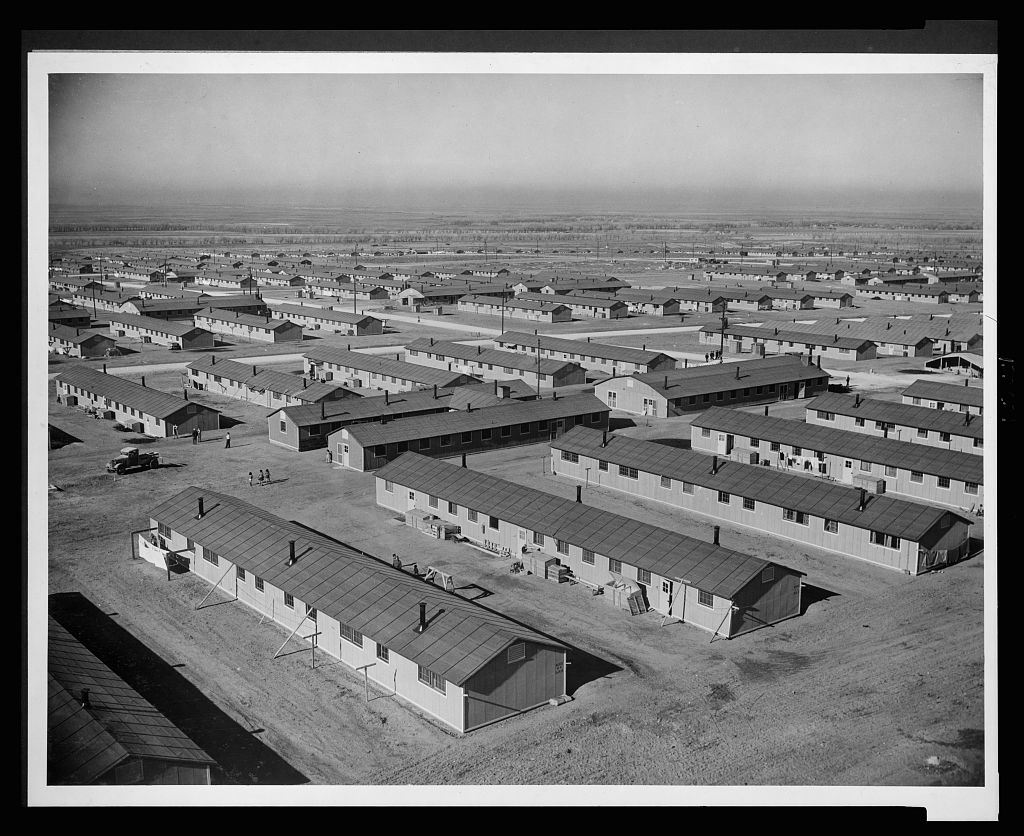

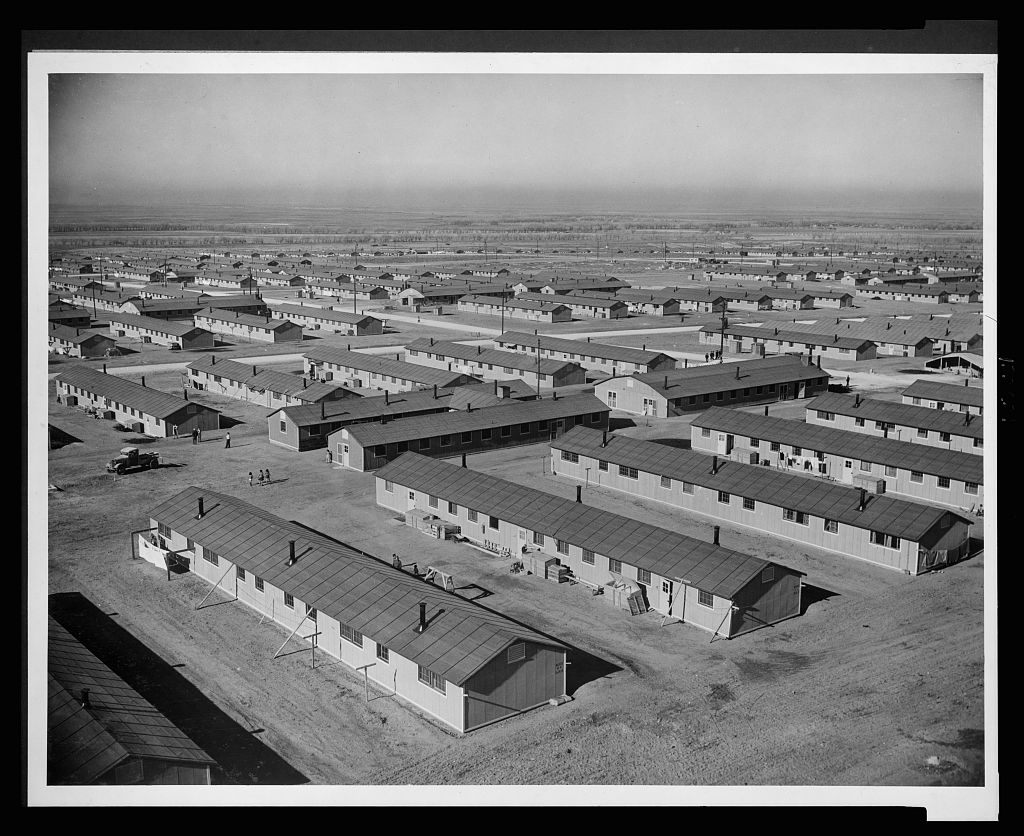

Library of Congress: Panorama of Granada Relocation Center, Amache, Colorado[9]

Amache Is Established

The full title of this gelatin silver print is very informative. It tells us that in the foreground is a typical barracks unit consisting of twelve apartment buildings, each with six-room, a recreation hall, laundry and bathhouse, and the mess hall. The Camp was built by the “Army Engineers” (United States Army Corps of Engineers). The Relocation Center was made up of 30 such blocks complimented by hospital buildings, administrative office buildings, living quarters, general warehouse structures and Military Police quarters.

Life Behind The Wire

Please don’t take this caption to mean that any of the internees had a private six room “apartment”. There were six “compartments”[10] in each barrack and none of them had running water, all meals were eaten seated by peer group in the large mess hall which seated about 250 people at a time. Of course, the food was by and large totally alien to the Japanese and the seating by peer rather than family had a deleterious effect on the Japanese family unit.

Almost all activities in the barracks were public. The National Park Service[11] tells us that “cramped, shared spaces and communal dining and bathing robbed incarcerees of their privacy, forcing them to adapt, subvert, and redefine private spaces.” The Japanese had no privacy in the shower or on the toilet! There were no dividers or walls.

Almost all activities in the barracks were public. The National Park Service[11] tells us that “cramped, shared spaces and communal dining and bathing robbed incarcerees of their privacy, forcing them to adapt, subvert, and redefine private spaces.” The Japanese had no privacy in the shower or on the toilet! There were no dividers or walls.

Marcia Yonemoto, a descendant of Amache internment camp, tells us that “there were no partitions between the toilets, no enclosures around the showers. So, in the middle of the night, there were blackout conditions, you could barely see anything, and you were more likely to sit on another person on the toilet than to sit on the toilet itself.”[12] Above is a view of a reconstructed barrack, a guard tower, and the Amache water tower[13] as they look today

The Dark Side[14]

We want to tell you about the children, about play, resilience, and marbles in Amache, but before we do that we need to detail a bit more about the ugly situation in the camps.

Seven people died in the camps as the result of gunfire by the Military Police and other soldiers. While in Amache much of the policing was conducted by the Japanese Americans themselves through their established internal administration. However, the rifles which the Military Police and other soldiers carried were very real and loaded. See the photograph below.[15] We have seen a photograph of a machine gun in a guard tower similar to the guard tower in the photograph above.

Seven people died in the camps as the result of gunfire by the Military Police and other soldiers. While in Amache much of the policing was conducted by the Japanese Americans themselves through their established internal administration. However, the rifles which the Military Police and other soldiers carried were very real and loaded. See the photograph below.[15] We have seen a photograph of a machine gun in a guard tower similar to the guard tower in the photograph above.

This photograph shows the evacuation of Japanese Americans from West Coast areas under United States War emergency orders. The citizens are waiting for registration at the Santa Anita Racetrack reception center in Arcadia, California.

Regrettably, evacuees at Santa Anita Racetrack were forced to live in horse stalls for three or four months before they were moved on to Amache[16]. Remember, these people had been forced to sell their comfortable home and profitable businesses for pennies on the dollar.

The guard towers in each camp were manned twenty-four hours a day. The guards were tasked to watch for fires in camp because some people had pot-bellied stoves in the barracks. The guards also worked, in association with the individuals chosen by the people, to keep order in the camps and to keep the internees safe from any internal or outside trouble.

They also monitored traffic and looked for contraband coming into camp like liquor, guns, or cameras. There were just over one hundred Military Police in Amache and an internee served as chief of police.

Remember, some if not all of these Japanese Americans had been gathered from their homes by soldiers with rifles and fixed bayonets. And there was concern among some of the internees about the guards. Derek Okubo quotes his father, a citizen of the camp: “Well, if they were put into the camp to [protect us] from harm then why were the guns pointed in and not out?”[17]

Violence in the Camps[18]

At the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah, 63-year-old prisoner James Hatsuki Wakasa was shot and killed by military police after walking near the perimeter fence. Two months later, a couple was shot at for strolling near the fence.

In Lordsburg, New Mexico, prisoners were delivered by trains and forced to march two miles at night to the camp. On July 27, 1942, during a night march, two Japanese Americans, Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were shot and killed by a sentry who claimed they were attempting to escape. Japanese Americans testified later that the two elderly men were disabled and had been struggling during the march to Lordsburg. The sentry was found not guilty by the army court martial board.[19]

And finally, one more. In October 1943, the Army deployed tanks and soldiers to Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California to crack down on protests. Japanese American prisoners at Tule Lake had been striking over food shortages and unsafe conditions that had led to an accidental death in October 1943. At the same camp, on May 24, 1943, James Okamoto, a 30-year-old prisoner who drove a construction truck, was shot and killed by a guard.

And finally, one more. In October 1943, the Army deployed tanks and soldiers to Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California to crack down on protests. Japanese American prisoners at Tule Lake had been striking over food shortages and unsafe conditions that had led to an accidental death in October 1943. At the same camp, on May 24, 1943, James Okamoto, a 30-year-old prisoner who drove a construction truck, was shot and killed by a guard.

Now a Look On The Brighter Side

Here are an archaeologist and a Park Ranger checking out a feature at Amache Camp[20].

James G. Lindley, who spoke out favorably in support of the Japanese Americans, was director of Amache.

Ralph Carr was Governor of Colorado 1939 – 1943, and he, too, unlike other Governors, welcomed the Japanese. Governor Carr publicly stated that he opposed the racial prejudice against Japanese Americans during WWII. Japanese Americans were relocated to Camp Amache only because they were racially Japanese. Governor Carr stated that all Japanese Americans were welcome to come to Colorado, and in fact many were hesitant to leave the Camp and they did relocate to Colorado upon release.[21]

Making Life Better While Inside

The government supplied the Japanese Americans with food and clothing allowances and a monthly wage. Their food allotment was 45¢ a day. Since American food did not suit their palates, “they grew many vegetable crops not previously grown in the southeastern area of Colorado. These included celery, spinach, head lettuce, potatoes, lima beans, onions, tea, mung beans and daikon (Japanese long radish).

In addition to the vegetable crops, the inmates grew field crops such as hay, alfalfa, and sorghum for the chickens, pigs, cows and other animals raised on the farm.[22]”

There was always too few workers, but the food grown was enough to reduce the needed food allotment to 31¢ a day. The farm was extremely successful and the Camp was self sufficient in food production. Surplus food went into the United States Military and some was sold locally.

The National Park Service tells us that Amache had the highest rate of Military volunteerism of all ten camps: 10% of the population served. They served in the “highly decorated” 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the Women’s Army Corps, and the Nurses Corps. Internee soldiers were awarded 38 combat pins and badges for conduct under fire. Nearly three dozen Nisei died in the War.

Once the draft was implemented, 11 Amache men were sentenced to prison for draft evasion.[23]

School & Social Life

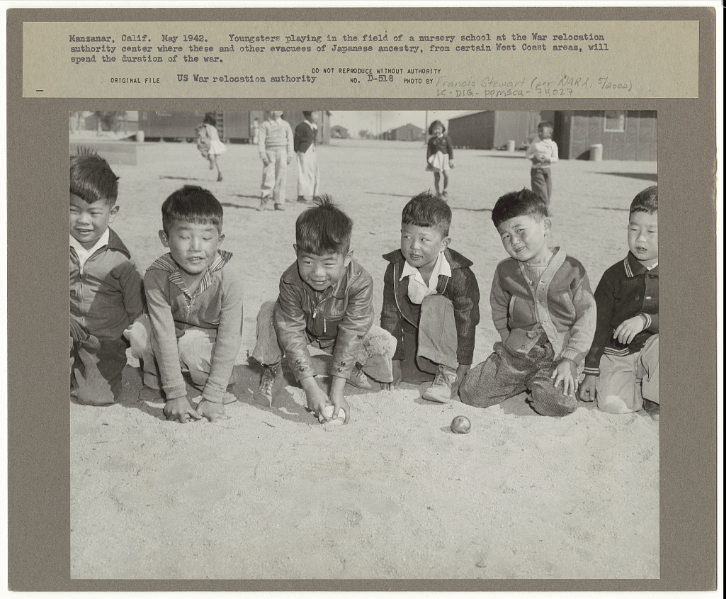

Children went to elementary, junior high, and high school in Amache. This photograph shows children playing in a field of a nursery school in Manzanar, California, in May 1942[24].

School sports were very popular in Amache. It must have been both fun and amazing to watch the Amache basketball win game after game. Their progress was reported to the people in Camp by the Amache Pioneer which was published from 1942 – 1945. The paper was published semiweekly from October 28, 1942 – September 15, 1945 and you can read it online at the Library of Congress Chronicling America[25].

School sports were very popular in Amache. It must have been both fun and amazing to watch the Amache basketball win game after game. Their progress was reported to the people in Camp by the Amache Pioneer which was published from 1942 – 1945. The paper was published semiweekly from October 28, 1942 – September 15, 1945 and you can read it online at the Library of Congress Chronicling America[25].

The schools taught adults typing, fine arts, handicrafts, and dressmaking. The internees could also go to the movies, theater, talent shows, the Amache library, YMCA & YWCA, the American Legion, and Boy and Girl Scouts.

A basketball game was held as part of the athletic events at the New Year’s Fair, Jan. 2, 1943, Poston concentration camp, Arizona. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration[26]

For mothers who had lost an immediate family member in the War there was a Blue Star Mother’s Club. There were musical clubs, literature, bridge, sumo, table tennis, and judo and board games like go and shogi.

For mothers who had lost an immediate family member in the War there was a Blue Star Mother’s Club. There were musical clubs, literature, bridge, sumo, table tennis, and judo and board games like go and shogi.

There was a silk screen shop at Amache which “created thousands of posters for the American military and became the largest program of its kind in the country.[27]”

And, finally, there was church. Buddhist, Catholic, Seventh Day Adventist, Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian worshiped there.

Gardens Were An Important Part of Daily Life Inside Amache Camp

We’ve talked about the bountiful fields of crops just outside the Camp at Amache, but there was also a lot of growing going on inside the wire. We learned about Dr. Bonnie J. Clark and her benchmark archaeological work at Amache early in our research and we communicated with her several times by email. See our “Additional Readings & References” section to learn the details of her 2020 book about the gardens at Amache.

She is a professor of anthropology at the University of Denver. Her new book traces six field seasons of her research and “immersion into the gardening lives of Japanese Americans held at the Amache prison camp…”

Dr. Clark says this about the Amache gardens: “Japanese philosophy toward nature and gardens converges with findings from horticultural therapy in compelling ways. Together they suggest that gardening was a practice uniquely suited to contribute to the resiliency of the Japanese Americans confined in all camps during WWII.

“At Amache,” she continues, “ we are really lucky to have such good physical integrity of the gardens that we can rediscover so much of the strategies and energies they put into these gardens. They reveal so many compelling ways gardening connected people to each other and to nature.”[28]

She explains that there were three distinct types of gardens inside the Camp. First are entryway gardens flanking the barracks doorways. Some of these use traditional Japanese design techniques. Second, there were ornamental gardens in public places, and finally there were vegetable gardens. And the Japanese Americans planted lots of trees for shade.

Photograph of Transitional Yasuda marble courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia

Dr. April Kamp-Whittaker

We will focus on boys since they were traditionally the most fervent marble players in Camp. Dr. April Kamp-Whittaker is now a faculty member in the Department of Anthropology and at the Museum at California State University Chico. However, while at the University of Denver, she wrote her Master Thesis under the advisement of Dr. Bonnie Clark[30].

She is Co-Editor of the 2024 book Historical Archaeology of Childhood and Parenting: Materialized Experiences, Discourses, Identities, Places, and Meanings (Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology). We have full book details in our “Additional Readings & References” section.

Her Thesis is “Through the Eyes of a Child: The Archaeology of WWII Japanese American Internment at Amache.” Kamp-Whittaker tells us that marbles, like the blue one above, are the most common archaeological toy found at Amache. This marble was found on the surface at Amache. Photo courtesy of Julianna R. Ellis, Amache National Historic Site, Colorado

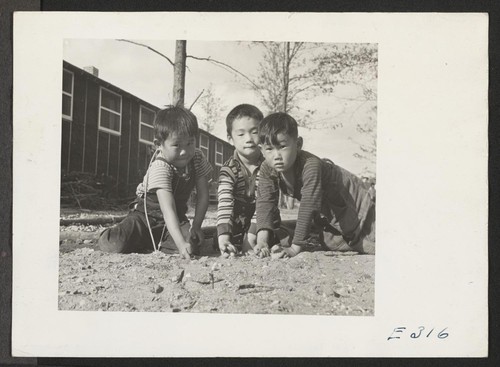

Students Playing Marbles: Mclellan collection under the Amache Preservation Society

Courtesy of John Hopper, Principal Granada High School and Leader of Amache Preservation Society[31]

Marbles & Child’s Play in Camp

The Camp structure set up by the WRA reduced parents’ supervisory and disciplinary presence in the camp. Certainly children played in organized sports and in communal structured play areas, but children spent more and more time with their peers.

Ironically, children realized more freedom and they felt safe in a clearly defined area bounded by barbed wire with guards both in towers and on patrol. Camp structure itself established an “apparently safe environment for children to play.” …Interestingly, the increased access to peer groups and the decrease in adult supervision which occurred in the camps worked to destabilize the restrictions around children’s movements.” (Kamp-Whittaker page 78)

Child development literature tells us that “unstructured play provides a safe space for children to explore their creativity without the constraints of rules or expectations. In mixed age groups, they are exposed to a wide range of ideas, interests, and abilities, fostering a sense of innovation and open-mindedness….This creative mindset can translate into their academic pursuits and future careers, enabling them to think critically and find innovative solutions to problems.”[32]

Bottom line: children get dirty in unsupervised play. When playing marbles they must establish on their own the rules of play. Playing marbles by its very nature means squabbles and disagreements. With no adults around to settle things children must resolve conflict on their own.

“Wild range” kids get bumps and scratches and they have to learn to cooperate, to compromise, and to explore and to cooperate with fr

iends and even those whom they don’t consider close buddies. All of these experiences are critical for learning and maturity and skills learned at unsupervised marble play are carried forward throughout the child’s life.

Where Did Children Play Most?

Amache marbles were recovered or found on the surface just about where the children lost them. We have seen this phenomenon many times. For example, we were exploring the sand lane in Bowling Green, Florida, near the old depot, looking for marbles on the surface and we found a small clutch of marbles near each other. We realized that the marbles were still roughly in the same place the children left them many years ago!

We have also spoken to older gentlemen who played marbles and were told that it was common to leave the marbles in place when play was over and sometimes they simply never got back to that particular game.

At Amache 50% of the marbles recovered were in low traffic area. They are found along the edges of the blocks “…and in or around landscape features.”

Marbles In The Nishikigoi Pond

When the Amache Preservation Society excavated the oval koi gardens and the pond they recovered about 11 marbles. Kamp-Whittaker tells us that such a collection of marbles in one feature is significant. “Marbles would have been difficult to recover if they were lost in the koi pond which explains their number.” (page 80) Marbles were also found in water features at Manzanar Camp which was about six miles south of Independence California.

You can see a striking photograph of recovered Manzanar marbles in the National Park Service article “Interweaving Living Stories and the Unburied Past: Community Archeology at Manzanar National Historic Site.” Like at Amache, “a high number of recovered marbles suggests children from many barracks were comfortable playing there — and that their guardians knew they would be safe there.”[33]

The Nishikigoi Pond In The Japanese Heritage

Koi fish are carp and they can grow quiet large. Nishikigoi translates literally to “brocaded carp.” “It’s unclear when koi made the transition … to an important symbol in Japanese culture, but it’s been believed for nearly two hundred years that the species shares the same bravery as the Samurai, due to its ability to overcome obstacles, swim upstream, and conquer waterfalls. Because of this nishikigoi have represented courage, strength, resilience, and perseverance in Japan for decades.”[34]

It is no coincidence that adults took a tremendous amount of time, effort, and energy to build gardens and especially ornamental koi gardens in the internment camps. We know that they spent considerable time there both working and meditating.

And it is no coincidence that children gravitated to the koi gardens to play. The gardens were Japanese with a long and proud heritage and they were places of supreme safety where children could play independently of adults. It was a safe place in the midst of an American-designed and structured environment where they were compelled to stay for an indeterminate time. Marbles and marble play were critical to children’s growth, independence, and sense of place in the camps.

Having Fun

“In interviews and informal conversations with former internees who would have been between the ages of 6-12 an idea of the freedom of children’s movement was developed. After the first year of internment, security at Amache was reduced, especially for members of the community who were not seen as a threat, like children.

As such there are repeated stories about leaving camp. These include collecting empty bottles and going into Granada to return them and going for cola and other treats at Newman’s Drug Store.[35]”

We wondered where the boys were getting their American-made marbles. We knew that mail order catalogs, especially the Christmas Catalog from Sears, Roebuck, and Co., were popular with the internees. But now we know that not only did children leave camp to shop but, at least at Newman’s, they found other Japanese Americans with whom they could relate.

“These forays into Granada may have occurred with some level of adult consent although 77 informants do not remember this aspect.”

“Other examples of leaving camp were definitely without adult supervision or consent. Tooru Nakahira was 7 years old when he lived in Block 12H which was located on the edge of the camp. In an informal conversation Mr. Nakahira recalled crawling under the fence and going to a guard tower which was no longer manned. He and his friends used it as a club house. Other boys remember leaving the camp to catch wild animals and bugs.” And turtles.

Wow! An abandoned guard tower, like this one at Amache, does sound like a wonderful place to play. This photo is courtesy of Julianna R. Ellis, Amache National Historic Site, Colorado

Wow! An abandoned guard tower, like this one at Amache, does sound like a wonderful place to play. This photo is courtesy of Julianna R. Ellis, Amache National Historic Site, Colorado

“One girl recalls that her brother had ten turtles which he had caught outside of camp. That children and other internees were leaving camp is documented in an article in the Granada Pioneer which reminded individuals that the water in a popular swimming hole located outside the camp was not safe.

Mr. Nakahira also remembers the repercussions of leaving camp without adult authorization. He and his friends were picked up by the Military Police (MP) patrol which drove around Amache. The MPs reminded the boys that they were not allowed to leave camp and drove them home….Although they were staying in the general vicinity, not venturing further than Granada a few miles away, they had a wider range of mobility than expected.” (Kamp-Whittaker pages 76-77)

Windswept

Amache is quiet now, except for the wind blowing across the Arkansas River Valley and the High Plains. This place was once called Amache City in the press all across the Valley. But now there are no more basketball games, no singing, no judo matches, and no snipers in the towers. No pond; no nishikigoi.

Some landscape features and building outlines remain. And stories remains to be recovered. One hundred and six people died in Amache and the Japanese-landscaped Cemetery is still beautiful and it still holds eleven graves. Most were voluntarily removed after the Camp’s closure in 1945.

There are no more weddings, and no more births nor deaths. And there are no more clandestine “escapes” to Newman’s Drug Store; the turtles in the nearby ponds are safe now from turtle-naping. Except for visitors, and we’re happy to report that the numbers continue to grow, it is quiet in Amache.

But Michi Weglyn reminds us that “most of the 110,000 persons removed for reasons of ‘national security’ were school-age children, infants and young adults not of voting age.”[36]

Americans must never forget what happened inside the wire and all across the sixteen square miles of pastureland and produce fields which the Japanese Americans tended with such skill and success. They sent surplus food to the Army; and many sent their children as well. Almost three dozen Nisei soldiers from Amache died in defense of America in World War II.

And children played in Camp. We must never forget nor overlook this fact. Children supervised themselves and they played marbles. We read online that one man left two buckets of marbles in his camp when he was relocated with his parents. Every marble found in Camp has a story. A story of resilience, of independence, and amazingly a story of freedom. While most of Amache Camp is gone; while most of the children who played there are gone; the marbles remain. And that is exactly how it should be.

Photograph of Yasuda marbles courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia

Additional Readings & References

Throughout this story we have provided a number of sources where you can both read and view more material about the World War II Japanese internment camps and life inside during the War. However, here are additional materials which you might find of interest.

A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II @ https://www.nps.gov/articles/historyinternment.htm 8/19/2024

Clark, Bonnie J. Finding Solace in the Soil, Archaeology of Gardens and Gardeners at Amache. Denver, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2020.

“Conference with General De Witt” @ https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/conference-de-witt 8/18/2024

Cuevas, Eduardo, & Lauren Villagran. “Government uses site of World War II internment camp to detan immigrants.” USA Today Tuesday, August 26, 2025, p. 5A.

Harvey, Robert. Amache: the Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado during World War II. Dallas, TX: Taylor Trade Pub.; Distributed by National Book Network, 2023.

https://npshistory.com/publications/amch/index.htm 8/16/2024

“Internment History” is at https://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/index.html 8/19/2024

Kamp-Whittaker, April, Jamie J. Devine, and Suzanne M. Spencer-Wood, Editors. Historical Archaeology of Childhood and Parenting: Materialized Experiences, Discourses, Identities, Places, and Meanings (Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology). NY: Spencer, 2024.

She is Co-Editor of the 2024 book Historical Archaeology of Childhood and Parenting: Materialized Experiences, Discourses, Identities, Places, and Meanings (Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology).

Podcast 116: Uncovering the Gardens at Amache. Amache National Historic Site. @ https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/podcast-116-uncovering-gardens-at-amache.htm 8/26/2024

Weglyn, Michi Nishiura. Introduction by James A. Michener. Years of Infamy The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Footnotes

- Lange, D. (1942) Hayward, California, Two Children of the Mochida Family who, with Their Parents, Are Awaiting Evacuation. California United States of America Hayward, 1942. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, -05-08] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021669756/ 8/16/2024 ↑

- “Terminology What’s in a Word?” @ https://jamo.org/terminology/ 8/20/2024 ↑

- Camp Amache is now a National Historic Site. The National Park Service explains that Ameohtse’e (Walking Woman) was the daughter of O’kenehe (Ochinee/One-Eye), “a prominent Cheyenne Chief who was murdered during the Sand Creek Massacre. In 1861 Amache married John Prowers, who had come west to work with William Bent at Bent’s New Fort. Her father helped negotiate a treaty between the United States and the Cheyenne, and Arapaho Tribes to safely camp along Sand Creek during the winter of 1864–1865.” We don’t know how the area near Granada came to be called Amache and then Camp Amache when the Japanese arrived. Who assigned the name to the camp rather than just referring to it as Camp Granada? ↑

- https://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/camps.html 8/20/2024 ↑

- “Japanese American internment” @ https://www.britannica.com/event/Japanese-American-internment 8/20/2024↑

- “A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II” @ https://www.nps.gov/articles/historyinternment.htm 8/19/2024 ↑

- https://www.nps.gov/people/john-lesesne-dewitt.htm 8/20/2024↑

- A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation…” ↑

- Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog, United States War Relocation Authority [1942], [Photograph], Call Number: LOT 10617, v. 14, p. 145 [P&P], Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003689106/ 8/22/2024 ↑

- Library of Congress, Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History. “Life Behind the Wire”. ↑

- “Life Behind Barbed Wire.” National Park Service, Amache National Historic Site, https://www.nps.gov/amch/ 8/22/2024 ↑

- Wingerter, Justin. “The Amache internment camp, as told by Japanese American survivors and descendents.” The Denver Post, May 20, 2021. @ https://www.denverpost.com/2021/05/20/amache-internment-camp-colorado-stories/ 8/22/2024 ↑

- A special thank you to John Hopper, The Amache Preservation Society (https://amache.org/amache-preservation-society/), Granada, Colorado, and to Juliana R. Ellis, National Park Service, Amache National Historic Site. Check out the University of Denver Amache Research Project (https://www.facebook.com/DUAmacheResearchProject/) for links to videos, and a very full photograph album of their work at Amache.↑

- Photograph of modern Japanese marbles courtesy of Josh Bates who lives in Jacksonburg, West Virginia ↑

- Digital ID: (digital file from original item) ppmsca 38735 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.38735; Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-38735 (digital file from original item); Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print ↑

- “The Amache internment camp, as told by Japanese American survivors and descendents.” ↑

- “The Amache internment camp, as told by Japanese American survivors and descendents.” Photograph of Yasuda marbles courtesy of Josh Bates who lives in Jacksonburg, West Virginia ↑

- “Violence in the Prison Camps” @ https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese-american-relocation#violence-in-prison-camps 8/22/2024 We have only referenced a few of the stories from this site. You might want to check it out to see more. Also see Koji Lau-Ozawa, “Legacies of Confinement: Violent Structures at Japanese American Incarceration Camps.” March 8, 2022 @ https://items.ssrc.org/where-heritage-meets-violence/legacies-of-confinement-violent-structures-at-japanese-american-incarceration-camps/ 8/23/2024 ↑

- The Lordsburg Camp was actually about three miles east of Lordsburg. You might want to cross-check “Lordsburg New Mexico” @ https://njahs.org/confinementsites/lordsburg-internment-camp/ 8/23/2024 ↑

- Special thank you to Juliana R. Ellis, National Park Service, Amache National Historic Site. ↑

- https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/granada-war-relocation-center-amache 8/23/2024 ↑

- “Agriculture at Amache” Amache.org @ https://amache.org/agriculture-at-amache/ (8/25/2024) & “Remembering Amache, a Japanese Internment Camp in Colorado,” by Mikaela Ruland ; Updated Feb 16, 2024. 8/25/2024 ↑

- “Amache, Colorado WWII Granada Relocation Center Prowers County, Southeastern Colorado” @ https://npshistory.com/publications/amch/index.htm 8/25/2024 ↑

- Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC ↑

- @ https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83025522/ (8/26/2024). You might want to check out the Editor’s poignant last letter “Lauds Pioneer Staff”. ↑

- Ctrl. #: NWDNS-210-G-A856, NARA ARC #: 536659, WRA, Photographer Francis Stewart,Densho ID: ddr-densho-37-471 ↑

- “Granada War Relocation Center (Amache). History Colorado. Colorado Encyclopedia. @ https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/granada-war-relocation-center-amache 8/26/2024 ↑

- https://liberalarts.du.edu/news-events/all-articles/du-archaeologist-examines-gardens-amache 8/26/2024 ↑

- WRA no. E-316. War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement. Contributing Institution: UC Berkley, Bancroft Library. Special thank you to Linda Salem, Assistant Head of Collection Development, Education Librarian, San Diego State University, and to Ryan Haynes, Research, Instruction, and Outreach Services Specialist, San Diego State University, and Michael Maire Lange Copyright & Information Policy Specialist

Scholarly Communications, Berkley Library, University of California ↑ - Kemp-Whittaker, April. “Through the Eyes of a Child: The Archaeology of WWII Japanese American Internment at Amache.” (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 326. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/326 ↑

- There is a goldmine of Amache materials and photographs at their website: https://amache.org/project-team/ 8/30/2024 ↑

- https://www.earlychildhoodeducationandcare.com/bloggers/2023/4/18/the-hidden-benefits-of-unstructured-play-in-mixed-age-groups-for-children 8/30/2024 ↑

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/community-archeology-at-manzanar.htm 8/30/2024 ↑

- https://www.bokksu.com/blogs/news/what-do-koi-fish-represent-in-japanese-culture? 8/30/2024 ↑

- “Before the opening of the camp, Edward Newman rented one of the largest buildings in Granada and brought in stock he thought would appeal to the inmates, including an entire warehouse of saké. Newman employed Amache inmates in the store and also as the family nanny, a practice fairly common in the area. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Amache_(Granada)/ 8/30/2024 ↑

- Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy, quoted in “Internment History” kimina@children-of-the-camps.org ↑