As Imagined Copilot – Microsoft

Back To The Abyss

We recently published “Limestone Marbles & The Eutaw Farm” which is about fossiliferous or shelly limestone marbles. Tons of these marbles were made in Germany and exported during the 19th century. This type limestone is chock full of marine fossils and shells or shell fragments. It may also contain coral and all sorts of other marine organisms, all compacted and cemented over time.

In this story we wondered why, as a general rule, marine fossils are not obvious in the German milled limestone marbles. We learned a great deal about this type marble, and then we published the story and moved on to other research.

The “Limestone…” story also explored archaeological work in Baltimore at the Eutaw Farm and in our next story, “Marbles from The Caulker’s Homes: Historical Status Markers from Baltimore’s Iconic Past,” we continued to explore archaeological digs in Baltimore.

Eureka!

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

You can imagine our surprise when, while digitally browsing in the British Museum[1] , this marble popped up! Yes, this is what we thought a shelly limestone marble should look like! We have no idea what type sea plants these circles are, but we are confident that some of you who tumble marbles and polish them do know what they are. And those of you who enjoy geology and paleontology may also know. If anyone does know what these creatures were, please do use the Contact button and let us all know!

Down The Rabbit Staircase!

Here’s some notes from the British Museum’s data sheet on this marble. The marble dates to circa the 1st – 5th century AD and it was dug in Afghanistan circa 1841 by Charles Masson. The Museum acquired it in 1880 from the India Museum.[2]

The British Museum tells us that the “ball” or marble is made of “highly polished, white-spotted beige, coralline limestone.” We find this very curious. Someone, perhaps the archaeologist who dug the marble or the curator at the India or the British Museum, knew full well that this marble is made of coralline limestone. And if they understood that it is Reef coral, why did they not also know that the “white spots” are the skeletons of algae?

Copilot-Microsoft tells us that “coralline limestone is a type of limestone primarily composed of the skeletal remains of coralline algae, a group of red algae that deposit calcium carbonate in their cell walls. This type of limestone forms in shallow marine environments, typically in tropical or subtropical regions.”

Coralline or Reef limestone is typically not found in Afghanistan but rather in the Indian Subcontinent. And, interesting for further discoveries which we tell you about later in this story, in Buddhist Caves near Bagh town in Dhar district in Madhya Pradesh. Madhya Pradesh is a state in Central India often called the “heart of India.”[3]

More Artifact Intake Notes

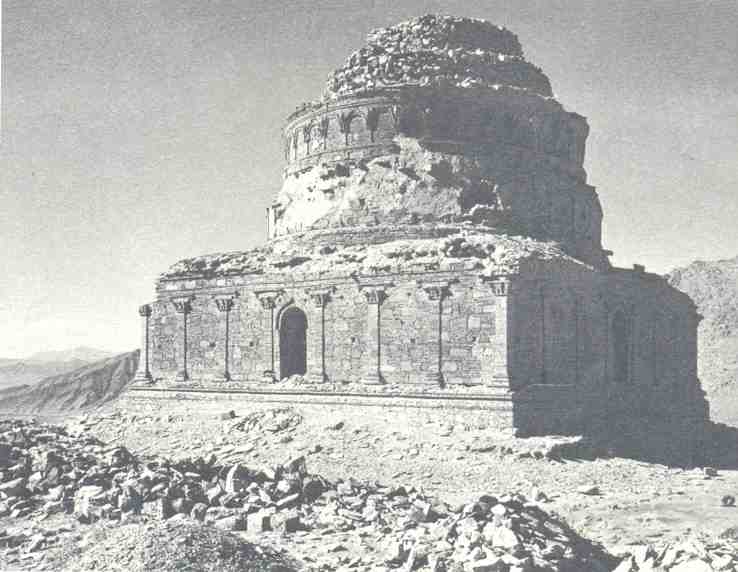

The marble was excavated in the Guldara Stupa, also known as Passani Stupa tumulus 5, in Afghanistan. Burials in this site are believed to be, as we noted above, around 2000 years old. The stupa dates back to the Kushan period, which flourished from the 1st to the 3rd centuries CE.

Afghanistan is predominantly Muslim today. The majority of the population practices Sunni Islam, with a smaller percentage following Shia Islam. Islam was introduced to Afghanistan in the 7th century.[4]

However, during the earlier Kushan period, when the Guldara Stupa was built, the region was Buddhist. Under the rule of Emperor Kanishka, the Kushan Empire reached its zenith. The empire played a significant role in the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and China, and it was known for its cultural and religious tolerance. The Kushans facilitated trade along the Silk Road and had diplomatic contacts with the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, the Aksumite Empire, and the Han dynasty of China.[5]

The Guldara Stupa: Afghanistan: Darunta: Passani: Passani Stupa ‘tumulus’ 5

Photograph taken August 31 2023

Weaveravel, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en No changes have been made to the image

Curator’s Comments

We volunteered for five and a half years at a small museum in Florida and we spent most of our time in curation of artifacts in the various buildings on the museum property. This can, at best, be satisfying work, but, depending on the artifact and its back story, it can also be frustrating. Remember that this marble was dug and field notes were written in 1841.

We were a bit surprised to realize that the marble is 18 millimeters in diameter That is, it is between 11/16th” and 12/16th” around[6]. That’s a perfect size for a marble, isn’t it? What other uses could the carver or polisher have had in mind?

“The material was identified in 2003 as coralline limestone by L. Joyner, Department of Conservation and Scientific Research. The ball was found in relic deposits ‘Box 3’, within a larger blue trimmed unnumbered tray now designated ‘B’, together with loose items which included clay ball (1880.3993.b) ….”

Say What?

First, no, we have not found that clay ball or marble. In these same notes, which you can read @ https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-3698/, the curator goes on to mention a tray from the South Kensington Museum and sixteen copper coins dug in another Stupa. The South Kensington Museum in London is now known as the Victoria and Albert.

We have studied every single word of the curation notes and they are complex. As for as the contents of the artifacts box or tray at the South Kensington Museum the curator noted that, along with beads and bronze coins, there were two marbles. The curator or staff were confident that the marble reported in the archaeologist’s field notes from Passani Stupa ‘tumulus’ 5 and this one are one and the same:

“…this small ball [the one featured in this story] is identifiable as the ‘small speckled spherical stone or marble’ found in Passani Stupa ‘tumulus’ 5 .., which best fits South Kensington Museum no.1026: ‘Marble ball’. Franks [no more information on Franks] misidentified the larger black stone ball 1880.3983.i (probably from Hadda Stupa 3) under IM.Metal.128 as ‘Stone ball or marble found in … tumulus no.5 Passani’. IM.Metal.128 has been reassigned to the correct Passani ball here. According to Masson (Wilson 1841, p.95): A ‘few corroded copper coins, amongst them one of the horseman type or of the Azes family’, were found near the summit of the mound. ‘Some distance below them was found a small spherical stone or marble, an intentional deposit, being placed exactly in the centre’. Emphasis added.

Masson is the gentleman who dug the mound. Remember, in or about 2003, the curator was some 162 years removed from the dig! We are surprised that she or he could do such a fantastic job unraveling the artifacts and then matching them correctly to the dig notes.

And there is that “larger black stone ball” which at first was confused with our marble. You can see it and its particulars @ https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-3983-k.

© The Trustees of the. British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0

International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

Right now it is not on display. The curation notes on this stone interlock with the notes on the Reef marble which is the lead of this study. There is simply no possible way to confuse our limestone marble with this one, and when the dig notes were studied carefully the curators realized their mistake.

When untangled, we realize that, according to the comprehensive field notes, the Reef marble undeniably came from Stupa 5 while this black stone marble came from Stupa 3.

Steatite Ball

This marble is larger than the limestone at 1.06”. It weighs 1/179 oz. In the Museum it is designated as a marble with a second designation of “sling-shot”. It does look like the ancient sling shot ammunition we found scattered across the deserts close to North Al Yahar community near Al Ain the United Arab Emirates.

It is dated to the late 1st century and is made of steatite. Steatite is also called soapstone or talc. It is used for countertops, flooring, and fireplace bricks. Both Afghanistan and India have reserves of steatite and both produce it.

Can our friends in the “Sphere Making World” use the Contact button to tell us how they made this marble some 2,000 years ago? Why is it so planar? Since it dates to about the same time, the same period, the same religion, and the same peoples, does anyone have any idea why this stone was left as it is while the limestone is not at all planar and it is polished and shiny?

Talking To The Walrus[7]: Stupas, Tumuli & Topes

There is no need here for a long complex pedantic thesis using confusing foreign words. On the other hand it is difficult to explain the importance of Charles Masson’s finds in Afghanistan, to include these and other marbles, without some definition of terms such as stupa and tumulus which we have already used in this story.

First, as odd as it may seem, remember that we are writing about archaeological digs in Buddhist structures in Afghanistan rather than in Muslim mounds. When Masson was digging the tombs, which he sometimes called sepulchers, he was living and working in a Muslim culture.

A Stupa, like the Guldara in the photograph above, is simply a mound. Generally, since stupa contain the earthly remains of Buddhist monks or nuns, they were very important in the Buddhist community, and they are historically used for meditation.[8]

Tumulus is a very generalized term for a burial mound. Unlike stupas and topes, which are specifically related to Buddhism, tumuli are used in a wider range of burial practices across different cultures and time periods. Tumuli are ancient burial mounds that were built over graves. They are found in many cultures around the world and often signify the resting place of important individuals or groups. These mounds can vary in size and shape, and they are typically made of earth and stones.

Closer to Home

Bring to mind your visits to Native American mounds. These mounds are tumuli. Burial mounds have always been fascinating. Thomas Jefferson conducted an archaeological excavation of a Native American burial mound in 1784 near the Rivanna River. This mound was part of a cluster of thirteen mounds in the Piedmont, Blue Ridge Mountains, and Shenandoah Valley regions. Jefferson’s finding are included in his book Notes on the State of Virginia.[9]

The term “tope” is often used interchangeably with “stupa,” particularly in South Asia. It refers to the same type of Buddhist structure used for meditation and housing relics. In essence, stupas and topes are specific to Buddhist traditions, while tumuli are more broadly used in various ancient burial practices.

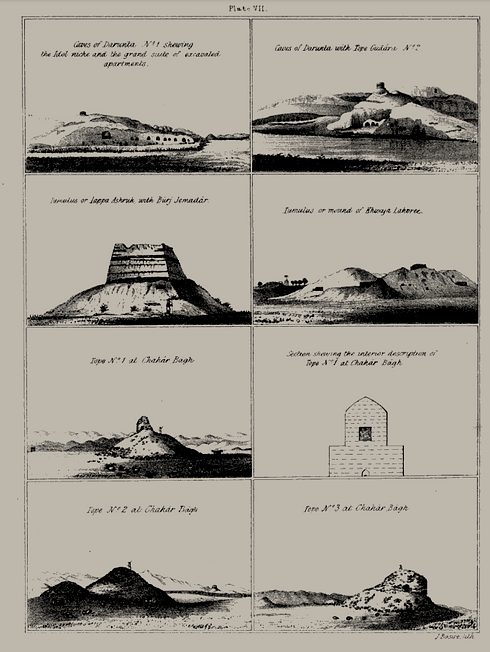

An Example Of Topes & Tumuli From C. Masson Ca.1840s

The sketches above are from the book Ariana Antique by Charles Masson. This is the book that contains the passage about Masson excavating the limestone and steatite marbles from the very center of the topes.

We think some of these sketches were drawn by him and others were contributed for Plate VII[10]. The sketch upper left is of the caves of Darunta. This one, Masson tells us, shows the “Idol niche” (far left in mound) and the “grand suite of excavated apartments.” We can only imagine that this is where the nuns’ and monks’ relics were stored.

The upper right sketch shows about three caves and Masson calls this Tope Gudára No. 2.

Second row, far left, shows a nice mound which we now know is a tumulus. That structure on top is called Burj Jemadár.

Look at that beautiful mound in the second row far right. All Masson tells us in the sketch is that it is the mound of Khuraga Lahore.

Third row left is “No. 1 Tope at Chahár Bagh. We can’t be certain but the name may also be Charbagh, which is a Persian name referring to what we would call in America formal gardens.

The image that looks a bit like an outdoor grill is a sketch from the interior of No. 1 Tope at Chahár Bagh. The bottom two photographs are also at Chahár Bagh.

In the book Ariana Antique Masson goes into excruciating detail about his finds in each of these mounds. And, also, as you might expect, his narrative includes stories of the local officials and warlords at times taking exception to his digging and the situation often became very tense.

Understanding The Tumuli In The Kabul River Valley

The reason that we show this plate is because we want you to realize that the terminology isn’t just dry and dusty. All of these mounds are, and in many cases, remain real places that, with some effort, you can visit today. The mounds are varied just as our own Native American mounds are extremely varied.

I’m sure many of us have visited The Serpent Mound, almost certainly built by Adena and “renovated” or modified by the Fort Ancient peoples. This one is in Adams County, Ohio. Then there is the Criel Mound in downtown South Charleston, West Virginia, the Cahokia in Illinois, and the flattop Bear Creek Mound along the Natches Parkway.

We visit the Grand Village of the Natchez every time we visit Natchez, Mississippi. And, finally, we can’t remember how many times we have haunted the 61 acres of the Crystal River Archaeological State Park in West Florida. While there are fundamental similarities in all of these mounds, the mounds themselves are as different as the Stupa which Masson explored in the first half of the 19th century in eastern Afghanistan.[11]

Now that we know a bit about the cultural landscape of eastern Afghanistan during the Kushan period, which flourished from the 1st to the 3rd centuries CE, and we can now make comparisons to the Adena, Hopewell, and other American mounds built during the same period, we want to orient ourselves to the British “archaeology” of the 1820s – 1850s.

British Archaeology

First, 19th century British archaeology was not even as scientific as American archaeology of the same period. In Britain, archaeology was often seen as a branch of history and was closely tied to the study of classical civilizations and medieval history. British archaeologists were typically viewed as scholars and gentlemen, and their work was often funded by private institutions or wealthy patrons. The discipline was considered part of the humanities and was associated with the study of art history, geography, and classical languages.[12]

Even with this backdrop in mind, Charles Masson has been referred by at least one modern archaeologist as a looter. It is almost impossible to read his book Ariana Antique and not be reminded of one of the Indiana Jones… movies. And when we tell you more about the man who dug the marbles which are now in the British Museum the more you will be reminded of escapades from the movies.

The Man Who Never Was

Charles Masson, born James Lewis in 1800 (1800 – 1853), was a British soldier, explorer, archaeologist, and numismatist. He is best known for his remarkable discoveries in South Asia and Afghanistan. Masson’s adventurous life and discoveries have left a lasting impact on the field of archaeology and our understanding of ancient civilizations.

Lewis was born in London in 1800 and he led a quiet life as a clerk for a London firm. After a quarrel with his father, and possibly in a momentary snit, he joined the British East India Company’s Bengal Army Artillery at the age of 21. He served in the Presidency of Bengal. All of the British East India Company’s armies were made up primarily of Indian soldiers known as sepoys. There was a much smaller number of British Officers who provided leadership and training.

Lewis saw a great deal of action on the battlefield including the Siege of Bharatpur in 1826. Evidently, he was a good and brave soldier who got along well with others.[13] That is, until 1827 when he deserted with a friend, Richard Potter. Lewis now created Charles Masson. Potter changed his name to John Brown.

Potter and Masson were on the move and some 4,919 miles (7,915 kilometers) from home as the crow flies. But while Masson had deserted the British Army, he had not deserted the place he had come to love. He was not overly concerned about the geo-political situation, at times to his peril, but he had learned to appreciate the landscape, the history, and the geography of the region.

As Imagined by Copilot – Microsoft

As Imagined by Copilot – Microsoft

On The Lam

There was one major problem with Masson’s explorations and ramblings. The punishment for desertion was death. The two deserted in Agra, Uttar Pradesh. Agra is home to the Taj Mahal. This was not all friendly territory for either man.

They headed in a north-westerly direction to avoid detection by the British army. The two continued unnoticed and made a long journey through east and west Punjab, Sindh, Rajasthan, Balochistan, Iran and Afghanistan. Eventually, Masson was the first European to discover Harappa which dates to between 3500 and 1300 BCE.

Indiana Masson

This next bit is from Storytrails.[14]

“In the Punjab region, [Brown and Masson] met Josiah Harlan[15], an American adventurer with ambitions of ruling an Indian kingdom! Harlan had entered the court of the Punjab king Maharaja Ranjit Singh by representing himself as a doctor, soldier, scholar and statesman. His ultimate aim was to carve a kingdom for himself[16] by playing politics between two warring royal families in Afghanistan – the Durranis and the Barakzais. (Although he never realised that ambition, he styled himself as the ‘Prince of Ghor’.) Masson and Brown [lied to] Harlan that they were American explorers going to Afghanistan… The wily Harlan saw through their ruse, but he took them into his mercenary army. Masson and Brown soon realized that they had nothing in common with Harlan, and deserted his army too. This triggered a wave of desertion in Harlan’s militia and Harlan never forgave Masson.

Wow! Now the Two Are Deserters from Two Armies!

Coins, Coins, Coins: Work For The British East India Company

Along the way Masson developed a keen interest in numismatics. And there is hardly any wonder: While wandering he collected around 47,000 coins! And we all have a good idea where he dug many of them, don’t we?

Wasson was still wandering some six years after he deserted his post in Agra. You won’t believe what happened next! Masson was hired by the British East India Company! Remember, he deserted the Company’s Army in 1827 and then was hired by them in 1833! And they paid him between 1833 – 1838 to do what he was already doing!

They paid him to explore ancient sites—-mounds, tumuli, topes, and stupas—in southeastern Afghanistan. It was during this period when he explored near Kabul (remember the Guldara Stupa is relatively near Kabul), Wardak, and Jalabad that he made the sketches that we have studied. He surveyed hundreds of sites and his pioneering efforts in these areas laid the groundwork, locations, and parameters for more scientific archaeological work which was to follow.

Masson and Brown parted ways somewhere in the uncharted terrain and, unfortunately, we can find no real clues about his life alone, whether he joined a third army, and whether he ever got home to England.

Ariana Antiqua

This book named Ariana Antiqua[17] was born from Masson’s work for the East India Company. The words “Ariana Antiqua” can be translated from Latin to English as “Ancient Ariana”. Ariana refers to an historical region in Central Asia, which included parts of present-day Afghanistan, Iran, and surrounding areas while Antiqua means “ancient” or “old.”

The book, published in 1841, is 545 pages long. It contains text, maps, compass readings, the sketches we have seen and many others, and, since he could not photograph all of the coins that he found, he or someone on his team sketched them! The coin sketches are toward the back of the book. The book is intended to account for many of the artifacts that Masson excavated or found on his trips for the British East India Company.

Lhasa, Bar Chorten, the Western Gate or Pargo Kaling Gateway[18]

Lhasa, Bar Chorten, the Western Gate or Pargo Kaling Gateway[18]

There Is Much, Much More than Ariana Antiqua!

Ariana Antiqua is supplemented online by The Charles Masson Archive in the British Museum and British Library.[19] Here is a pullout from the Abstract which the Museum provides for the Archive: “This is the collection and archive created by Charles Masson (1800–53), the first European not only to explore and/or excavate the Buddhist monuments near Kabul and Jalalabad and the urban site of Begram, but also to document in detail what he found. His finds are a unique record of many ancient sites which are now lost or no longer accessible for research.”

And Then There Were None

We have just a few comments about those collections in the British Museum. Masson explored some sites never before seen by Europeans. His notes, maps, observations, sketches, and compass readings are all invaluable in their documentation of historic and religious sites. Remember, many of the tumuli that Masson documented are in Afghanistan. The marbles in this story were also found in Afghanistan.

And in Afghanistan researchers have documented over 37 archaeological sites which have been plundered by the Taliban leaving nothing but scores of empty holes all across unique and unrecoverable sites. Some of these sites date back to the Late Bronze Age (1200 BCE – 1150 BCE) and Iron Age (about 1200 BCE – 550 BCE). The destruction has accelerated and is still ongoing since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. The Taliban loot the sites for artifacts which can be sold.[20]

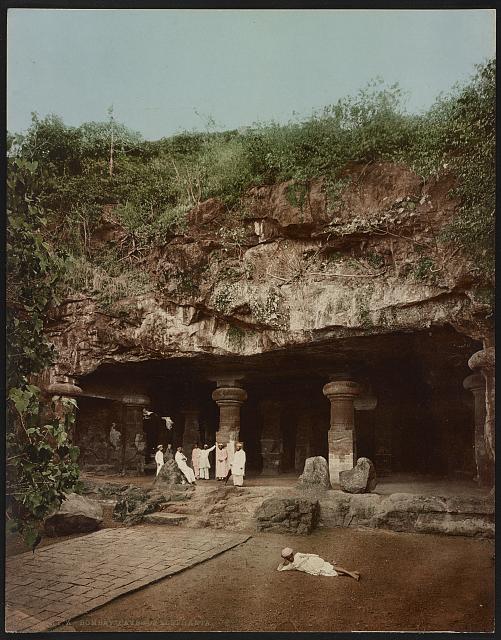

Elephanta & Salsette Islands

Eventually, Masson, who dressed as a local and who spoke several languages and dialects, returned to Bombay (Mumbai). There he spent some time surveying the Elephanta and Salsette Islands. We have no idea who hired him to do this work, nor do we know if he found coins. Eventually, Masson, who dressed as a local and who spoke several languages and dialects, returned to Bombay (Mumbai). There he spent some time surveying the Elephanta and Salsette Islands.

.

Bombay. Caves of Elephanta[21]

The Elephanta Islands are also known as Gharapuri (meaning “the city of caves”), are located in Mumbai Harbor. The islands are famous for their ancient cave temples, known as the Elephanta Caves.[22] The caves date back to between the 5th and 8th centuries CE and feature rock-cut sculptures dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva.

Incidentally, we’ve read that the Island and the Caves are home to some unpleasant monkeys. We experienced some pinching monkeys at the Batu Caves and temple near Kuala Lumpur while attending the Thaipusam festival. For the uninitiated, these monkeys can be a real and unpleasant distraction for visitors.

Soldier, Digger, Collector, Spy

We told you that Masson was a very capable British soldier. Well, he was an equally capable and cunning spy! Since he was wandering on his own and digging at will across the country-side, the British “…agreed to pardon him on the condition that he would spy on the Afghan king for the British. … If he accepted the offer, there was every chance that the king would find out and behead him; if he refused the offer, the British would execute him whenever he re-entered British territory.

Masson reluctantly accepted the offer. For a few years he lived dangerously, as an archaeologist who was secretly a spy. Masson supplied valuable intelligence, although the British often lacked the judgment to act on it. By 1838 the British decided to invade Afghanistan despite the reservations mentioned in Masson’s intelligence reports. However, Masson was relieved with full pardon.” (Storytrails https://storytrails.in/history/charles-masson-the-man-who-discovered-harappa/?form=MG0AV3)

It was only because of the pardon which he won being a spy that Masson was ever allowed back into England. And we are left to wonder exactly who did the British Army pardon: Lewis or Masson?

Masson’s Legacy Back Home

Finally, in 1842, Masson did return to England. We have no record of him ever using the name James Lewis again. When he got home he published the Ariana Antiqua. Storytrails tells us that he found very few readers interested either in his book or in his archaeological finds.

“He was perceived as a deserter, a discredited spy who said fanciful things. He was not from the established academia, and spoke too bluntly. Largely unrecognized, Masson died in 1853 [some references say 1855]. In 1855, his collections were bought from his heirs by the East India Company for just 100 pounds[23]. Most of the artefacts were later distributed to reputed organisations like the British Museum, Royal Asiatic Society, Victoria & Albert Museum, and so on. In 1995, the remainders – considered to be ‘mere rubbish’ – reached the British Library. When they opened the boxes, they were astonished to find that one man had achieved so much!”

Yes, he had deserted but he had also earned a pardon from the British government for that desertion. He was an effective spy although the government failed to listen or attend to his intelligence. The First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842) and British invasion of Afghanistan was the result. The British forces and their camp followers faced severe hardships and were almost completely massacred during their retreat from Kabul in January 1842. The British then retreated completely from the Country.

We can find no record that Masson ever attended college[24] and he was far from an academic nor was he in “mainstream” academic circles in England. But he was a dogged and capable academic archaeologist[25] who fairly embodied that technique in the mid 19th century. Even today in England you do not require a license to be an archaeologist.

This is what academic and researcher Elizabeth Errington[26] at the British Museum has to say about Masson’s legacy:

“It is all too easy to condemn 19th-century explorers and excavators of ancient sites as treasure hunters and desecrators. Some undoubtedly were, but arguably not to the destructive extent of modern clandestine diggers and iconoclasts. Charles Masson (1800–53) has also been dismissed in this way, but the present attempt to reconstruct and make public his extensive and meticulous unpublished records hopefully will not only exonerate him in the context of his times, but establish him as a pioneer in the field of archaeology at a time predating the concept of this discipline. Masson was also an instinctive numismatist, the first to realize the worth of creating as large a coin database as possible and recording patterns of distribution as a means for reconstructing the history of ancient sites and dynasties.” From her Preface P. 1

Who Got What?

As we noted above, the majority of Masson’s finds were eventually deposited in the India Museum in London and some reports note that the British East India Company received “all” of his finds. At any rate, the British Museum, where we found the digital image of the marbles, received the artifacts in 1878 when the India Museum closed.

We don’t think the British Museum got all of the coins, but it seems that they did receive all or most of the “archaeological” artifacts including the limestone and steatite marbles. The Museum accessioned reliquaries,[27] beads, marbles, and so many other artifacts from the tombs and then the Museum set about, as we have noted, to place them within a wider historical and archaeological context and to share them with the public.

The Beginning Is The End

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0

International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

We are now returning to the stupas, tumuli, and topes. Specifically, tumulus number five of Passani 1. We quote from page 95 in Masson’s Ariana Antiqua:[28]

“This is a large tumulus standing with its débris on a circumference of two hundred and twenty feet. It was opened at the summit near which we found a few corroded copper coins amongst them was one of the horse man type or of the Azes family[29] Some distance below them was found a small spherical stone or marble an intentional deposit being placed exactly in the centre. Finally towards the base surrounded by very large stones or boulders was a cupola of six feet in diameter and about eight feet in depth the conical portion of which was coated with cement and decorated with coarsely coloured flowers Nothing was found in the materials filling it but the beak of a bird supposed to have been a Maina[30] a deposit whatever signification may attach to it which has been found elsewhere as in Tope No 1 of Kotpur. On this tumulus a greater expense was necessary than on any of the topes we had examined.” Italics added.

The Stetite Marble

We will refer to Elizabeth Errington to describe where this black marble was found. Franks’ misattribution confirms this ball was included among the relic deposit finds. It also appears, together with the Passani example, to be listed as ‘two marbles’ under SKM 1062 (see Appendix 2, p. 219) and best fits Masson’s description of ‘a spherical black stone’ from Hadda 3 (E161/VII f. 18). In discussing an egg-shaped stone from Nandara Stupa 2, he says (1841, p. 85): ‘Other topes and tumuli have yielded stones, generally spherical ones; and as they are always found in the very centre of the structures, their insertion was intentional, and I suppose had a purport’. For similar Roman marbles or sling-shots, see www.britishmuseum.org, Collection Online: 1976,1231.153–4 Pages 166 – 167 Emphasis added

We are confident that Masson found other marbles but we have no idea where and how many.

Unanswered Questions

Remember, Masson was digging in what had been for centuries holy Buddhist sites. The function of a stupa has been described as “an engine for salvation, a spiritual lighthouse, source of the higher, ineffable illumination that brought enlightenment.” [31] Buddhist reliquaries in Afghanistan were essentially monastic complexes that included living quarters, meditation cells, and stupas (reliquaries). These sites were used for religious practices, education, and communal living by Buddhist monks and nuns. Some of the most notable sites include the Nava Vihara monasteries near Balkh, which served as major centers of Buddhist activity in Central Asia for centuries.[32]

As Imagined By Copilot – Microsoft

The marbles in this story were not excavated from reliquaries. That is, they were not taken from jars, caskets, or other containers which held the remains of Buddhist saints or significant artifacts from Buddhist history. These items were venerated by the faithful and often enshrined in stupas or other significant religious sites.

Here is a pullout from the Ariana Antique which gives some flavor of Masson’s excavation of a reliquary:

“there was found a large copper jar or vessel. Without it were thirteen copper coins, four pins of brass or copper gilt, three silver rings, and sundry minute ornaments, beads, &c. On opening the copper vessel it was discovered to be half-filled with a liquid as fluid as water, but discoloured by the verdigris [bluish-green patina ]of the metallic jar. In this liquid was deposited first a cylindrical copper gilt case, whose bottom, the effect of contact, had become corroded, and fell away as the case was extracted. This enclosed a series of deposits: first, a silver casket with cover, containing four thin silver coins which we have been accustomed to call Sassanian [the last pre-Islamic Persian empire, ruling from 224 to 651 CE], a small blue stone, and a mass formed probably of unguents[33]…. “ Page 108

Even More Unanswered Questions

The marbles in this story held perhaps an even more special and sacred place in the stupa. …Topes and tumuli have yielded stones, generally spherical ones; and as they are always found in the very centre of the structures, their insertion was intentional, and I suppose had a purport’. “Purport” is generally understood to mean the substance of something, or the reason for something, but in this case, what was the reason?

Why were these two marbles, and, evidently many more, so important to the Buddhist religious community? Why place them deliberately in the very center of the tombs?

We can only imagine that while Masson was diligent enough, within the bounds of archaeological practice at the time, to record the marbles and to include them with all of the other artifacts which he found in a stupa, and he described them like he did other findings, he did not find them of much significance to his goals. Remember, he was a numismatist. He was finding gold coins, along with other gems, silver caskets, precious beads, and so on. The marbles simply meant little to him.

But he knew that they must have been significant to the Buddhist who owned and perhaps made the marbles. And they were very special to the people who built the stupa. No, the marbles were not inside a reliquary as if they had belonged to and were relics of a particular nun or monk. Rather they were inside and in the very or exact center or heart of the stupa. They must have been sacred[34] to the community at large which built the stupa and placed them there.

Why were the marbles so special? Who made them? Can someone, perhaps in the Sphere Making Group, explain how they were made some 2,000 years ago? How could they, with the limited tools that they had, possibly polish the limestone marble to such a shine? Why leave the steatite marble with such harsh planar surfaces? Why not round and polish it too? If anyone has any ideas then please do Contact us.

Bottom Line

This is the very first story that we have written about marbles excavated by 19th century cultural archaeologists. We did write about the Egyptian marbles found by late 19th century archaeologist W.M. Flinders Petrie and Egyptologist James Edward Quibel who unearthed Predynastic (6000 – 3100 B.C.) Egyptian marbles. See Chapter One in our book The Secret Life of Marbles Their History and Mystery beginning on page 3. However, our exploration into the lives of these individuals is not extensive.

But in this story we have placed marbles firmly in the muddle or controlled chaos of early 19th-century socio- classical archaeology. At times Masson went and dug where no Europeans had ever ventured. There were significant advancements and discoveries driven only by the desire of certain individuals to explore, excavate, and collect “classical cultures’” artifacts, relics, and other material remains.

Important archaeological institutions and museums were established, such as the British Museum and the Louvre, which played crucial roles in preserving and displaying classical artifacts. The British Museum, which opened to the public in 1759, and the Louvre, established in 1793, played critical roles in collecting, curating, and displaying classical artifacts.

A Critical Analysis

Certainly, Masson and other 19th century archaeologists often used crude excavation techniques and, compared to today’s technology-driven standards, they were sometimes damaging to the artifacts, features, and remains which were uncovered. Much was lost, and we will never know how much. But it is critical to note that 19th century classical archaeology laid the ground work for our systematic and scientific archaeology of the 21st century. And remember, so much was recovered, archived, and placed in digital format for the public because of archaeologists like Masson and others.

Sorry! All those big words put me to sleep.

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-3698 1/11/2025 ↑

- “Museum (1801-79) of the British East India Company (1600-1858) and subsequently of British India (1858-1947) in London. It was originally housed in East India House in Leadenhall Street in the City of London… When the India Museum closed in 1879, the collections were principally divided between the British Museum, Kew Gardens and the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). The antiquities and archaeological collections, including c. 2420 coins, were mostly transferred to the British Museum (1880-82); some, however, initially went to the South Kensington Museum before being transferred to the British Museum, while the India Office retained some objects and the majority of the India Museum coin collections.” https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG10900/ 1/10/2024↑

- Coralline Limestone Formation 1/10/2024 ↑

- The Largest Religions in Afghanistan – WorldAtlas (1/11/2025) & Religion in Afghanistan – Wikipedia 1/11/2025 ↑

- Kushan Empire (ca. Second Century B.C.–Third Century A.D.) | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History & Kushan Empire – Wikipedia & Kushan dynasty | Central Asia, Silk Road, Buddhism | Britannica 1/11/25 ↑

- 1. Convert millimeters to inches:- 1 inch = 25.4 millimeters.- So, to convert 18 millimeters to inches:18 mm × (1 inch / 25.4 mm) ≈ 0.70866 inches2. Convert inches to 16ths of an inch:- There are 16 sixteenths in an inch.- So, to convert 0.70866 inches to sixteenths of an inch:0.70866 inches × 16 ≈ 11.34 sixteenths ↑

- “The time has come,” the Walrus said, To talk of many things: Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax— Of cabbages—and kings— And why the sea is boiling hot And whether pigs have wings.” From “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” a poem by Lewis Carroll from his book Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. ↑

- There is an excellent online travel report about a visit to the Guldara Stupa which we think you might enjoy reading. It was written by archaeologist and writer Ben Timberlake and it captures the essence of the place in “real time”: Ben Timberlake, “The Guldara Stupa (Artefact V)” September 3, 2024 @ https://www.tetragrammaton.com/content/guldarastupa (1/6/2024). You might also like to expand your horizons by reading about “The Largest Standing Stupa in Afghanistan: A short history of the Buddhist site at Topdara” by Jelena Bjelica January 8, 2020 @ https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/context-culture/the-largest-standing-stupa-in-afghanistan-a-short-history-of-the-buddhist-site-at-topdara/ 1/14/2025↑

- https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/jeffersons-mound-archaeological-site/?form=MG0AV3 1/17/2025 ↑

- Plate VII Ariana Antique No page number, but it is at the back of Chapter Two which ends on page 118. ↑

- You might want to familiarize yourself with some of these American mounds. If so then we recommend that you check: https://www.nps.gov/natr/learn/historyculture/american-indian-mounds-along-the-natchez-trace-parkway.htm; https://www.ohiohistory.org/visit/browse-historical-sites/serpent-mound/ ; https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=chochia+mounds#fpr=r; https://visitsouthcharlestonwv.com/things-to-do/criel-mound/; https://www.trailoffloridasindianheritage.org/crystal-river-archaeological-park/ 1/17/2025↑

- Paul Courtney, “Historians and Archaeologists: An English Perspective.” Historical Archaeology, 2007, 41 (2): 34 – 35. @ https://www.jstor.org/stable/25617438 1/18/2025 ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidency_armies & the fascinating online story “Charles Masson: The Man Who Discovered Harappa” April 4, 2023 @ https://storytrails.in/history/charles-masson-the-man-who-discovered-harappa/ 1/18/2025 ↑

- “Charles Masson: The Man Who Discovered Harappa” April 4, 2023 @ https://storytrails.in/history/charles-masson-the-man-who-discovered-harappa/ 1/19/2025↑

- Josiah Harlan (1799-1871) was an American adventurer and soldier of fortune, best known for his travels to Afghanistan and Punjab with the intention of making himself a king. He enlisted as a military surgeon with the East India Company in 1824, despite lacking formal medical training! @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josiah_Harlan?form=MG0AV3 (1/19/2025). You really need to get a look at this gentleman either at Wikipedia or Storytrails! ↑

- It is said that Josiah Harlan was Rudyard Kipling’s inspiration for the novella The Man Who Would Be King which was published in 1888. There is no evidence that Masson ever shared such an ambition. ↑

- Wilson, H.H. Ariana Antiqua : A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan With a Memoir on the Buildings Called Topes, By C. Masson, Esq. London: Published under the Authority of The Honourable The Court of Directors of the East India Company, 1841. The Library of Congress has a digitized copy of the whole book @ https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdclccn.10022371/?st=gallery 1/20/2025↑

- Norzunov, Ovshe M. Associated Name, and G. Ts Tsybikov. Lhasa, Bar Chorten, the Western Gate or Pargo Kaling Gateway. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, to 1901] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021670618/>. ↑

- Elizabeth Errington. The Charles Masson Archive: British Library, British Museum and Other Documents Relating to the 1832–1838 Masson Collection from Afghanistan. “The Charles Masson Archive is the second part of a trilogy of publications resulting from the Project and is designed as a linked online reference resource of unabridged records supplementing Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan: Explorations, Excavations, Collections 1832–1835 (Volume 1; British Museum Research Publication 215) and Charles Masson: Collections from Begram and Kabul Bazaar, Afghanistan 1833–1838 (Volume 3; British Museum Research Publication 219).”↑

- https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/south-asia/afghanista-taliban-archaeological-historical-sites-b2500425.html?form=MG0AV3 1/20/2025 ↑

- Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print 1/21/2025 ↑

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Elephanta-Island 1/21/2025 ↑

- In 1855, £100 British pounds would be equivalent to approximately $13,762.63 USD today. Certainly more than pennies! ↑

- We recommend that you check Elizabeth Errington’s “Part 1: Charles Masson and His Contemporaries in Chapter 1The Life of James Lewis/Charles Masson, 1800–53” in The Charles Masson Archive: British Library, British Museum and Other Documents Relating to the 1832–1838 Masson Collection from Afghanistan. ↑

- Stephen L. Dyson. In Pursuit of Ancient Pasts: A History of Classical Archaeology in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries . Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 2006. Published online October 31, 2013. ↑

- Elizabeth is a specialist in the archaeology of Gandhara and the collections of Charles Masson, as well as a numismatist focusing on Asian coins. She has made significant contributions to the field of Silk Road numismatics and has worked extensively on the Charles Masson Project at the British Museum. AI ↑

- A reliquary is a container or shrine used to hold and display relics, which are usually physical remains of saints, martyrs, or other holy figures, as well as objects associated with them. These relics can include bones, hair, clothing, or other personal effects, and reliquaries are often designed to honor and venerate these items. AI ↑

- Wilson 1841 / Ariana Antiqua. A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan (p.95) Errington 2017a / Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan: Explorations, Excavations, Collections 1832-1835 (p.99, fig.102, p.219, p.221) ↑

- These are unusual coins. You might want to see Indo Scythians, Azes I and Azes II – Ancient Greek Coins – WildWinds.com 1/22/2025 ↑

- The maina bird, also known as the myna or mynah, is a member of the starling family (Sturnidae). These birds are known for their vibrant plumage, distinctive calls, and remarkable mimicking ability. AI ↑

- Llewelyn Morgan. The Buddhas of Bamiyan. London: Profile Books, 2012. See also Jolyon Leslie, “Conservation of Buddhist Heritage in Afghanistan, 2016–2022.” Edinburgh University Press Journals @ https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/afg.2024.0121?af=R 1/23/2025 ↑

- “Deom_2011Buddhist_sites_Afghanistan_West_CA” Pdf ↑

- An unguent is a soft, greasy, or viscous substance that’s typically used for application to the skin. It’s often used for medicinal purposes, such as a healing ointment or salve. Historically, unguents have been used for centuries in various cultures for treating wounds, infections, and other skin ailments. Frankly, we are unsure why an unguent would be used in a reliquary unless it served as a preservative. We have not found Masson’s reference to unguents in other graves, but we do expect such finds were common. AI ↑

- We have written about sacred marbles before. See “Magic Mysterious Moqui Marbles” pages 217 – 229 in our book The Secret Life of Marbles Their History and Mystery. https://www.ebay.com/itm/146035336749 1/26/2025 ↑