In “Windswept”, which is the last section of our story Amache Marbles (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/amache-marbles/) we noted that one man left two buckets of marbles in his camp when he was relocated with his parents at the end of World War II. Each person could carry only a small bag or two of the family’s possessions when they were forced to leave camp and he had no choice but to abandon so many marbles.

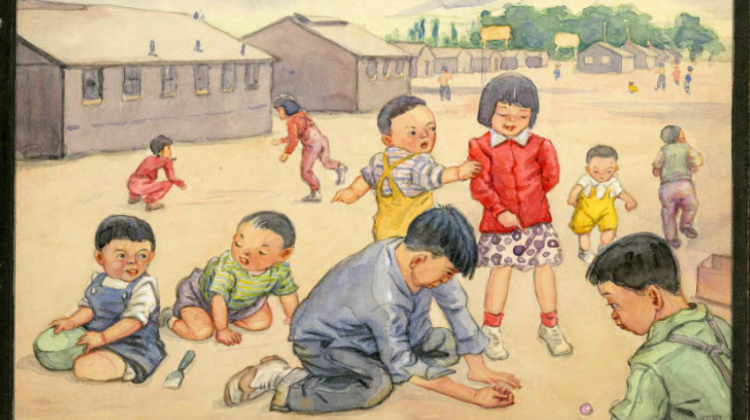

Well, those marbles belonged to Jim Matsuoka, an internee at Manzanar (“apple orchard”) who had won them fair and square. Our feature photograph above illustrates boys like Jim getting down to marble business at Manzanar.

Jeff Burton and Mary Farrell conducted and recorded the most enjoyable, readable, and relatable archaeological dig that we have ever hear of!

Jeff and Mary tell us that “in the spring of 2017 archeological investigations were conducted in Block 11 at Manzanar National Historic Site …The primary purpose of this work was to recover a cache of marbles, buried at the site in 1945 by 10-year old Jim Matsuoka, as part of a documentary project by artist and social justice activist Kyoko Nakamaru.” Jim was the little boy who was forced to abandon those marbles so long ago!

Entrance to Manzanar Relocation Center / photograph by Ansel Adams Courtesy Library of Congress[2]

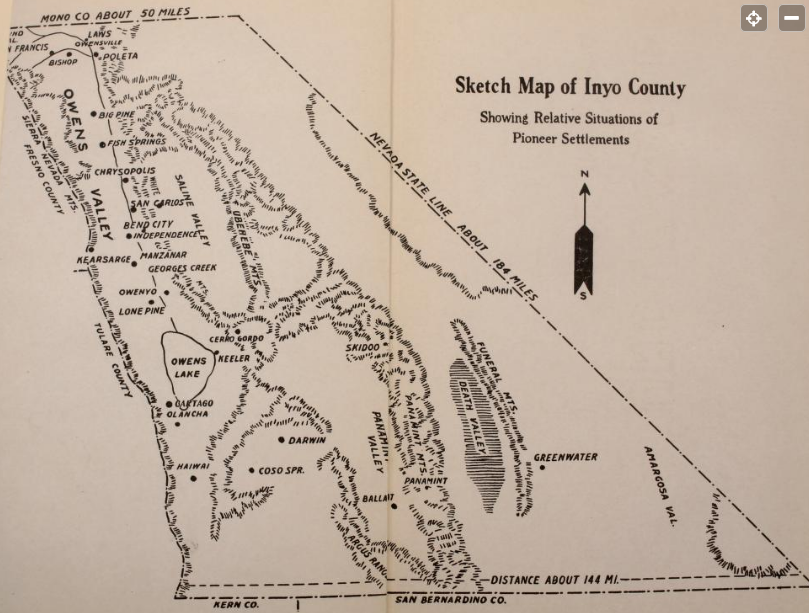

Manzanar, which is in Inyo County, California, is now The Manzanar National Historic Site. It is located in east-central California and it was the first internment camp opened. Eventually there were ten camps[3] holding approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans for varying periods of time.[4] Camps were located in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.

We discuss The War Relocation Authority (WRA), Executive Order 9066, the use of Military Police in the Camps, and general camp organization, in Amache Marbles (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/amache-marbles/) so we will not discuss those details in this story. Please oread back over Amache Marbles if you want to learn more details and background about the internment program.

Prime Real Estate

In each state the internment camps were built away from heavily populated areas. The National Park Service tells us that they were built in remote deserts, plains, and swamps….Manzanar, located in the Owens Valley of California between the Sierra Nevada on the west and the Inyo mountains on the east, was typical in many ways of the ten camps.”[5] The Camp was about 230 miles north of Los Angeles and a world away. The town of Lone Pine is to the south of the Camp and Independence is to the north.

Manzanar Orchards in Bloom NPS

Manzanar Community & Town

In the late 19th and early 20th century Manzanar was a small farming community. It was known far and wide for its delicious apples.

The National Park Service reports that in the early 20th century the Owens Valley Improvement Company planted thousands of apple, pear, and peach trees. The apple orchards produced prize-winning Winesap and Spitzenburg apples. After the Camp was opened Japanese Americans worked to maintain and harvest the orchards. The fresh fruit was used in Camp to supplement their food allowance.

We spoke with Heather Todd, Curator at the Eastern California Museum in Independence, about Manzanar and she told us that well before the Internment Camp was opened Manzanar the community and town had a long history. She grew up in the area, enjoyed her childhood, and told us about the creek and creek-fed water system and small reservoir built by the Government in 1942. We had never heard about the reservoir before.

Library of Congress [6]

Heather also told us about the development of the town of Manzanar. George Chaffey was an agricultural developer who bought much of the land and founded the town in 1910. Chaffey developed the area with the Owens Valley Improvement Company but the population grew slowly.

Chaffey’s Company built an irrigation system over thousands of acres and they planted about twenty thousand fruit trees.

By 1920 some 5,000 acres were under cultivation and the community grew apples, grapes, prunes, potatoes, corn and alfalfa, and large vegetable and flower gardens.

We will only mention the City of Los Angeles Aqueduct which was completed in 1913, but, as you can imagine, this had a dramatic and deleterious effect on Manzanar. By 1929 Los Angeles owned all of Manzanar’s land and water rights. Within five years, the town was abandoned.[7]

The Valley Before Manzanar: The Northern Paiute

Long before the birth and death of the fruitful Manzanar community and town, and before Joseph R. Walker, one of the first white explorers in the area, crossed the Valley in 1833, the Owens River Valley had been home to the Native American Paiute peoples. They had lived in the area for some 11,000 years.

Linguistically, the Paiute peoples spoke the Shoshone language and they are sometimes referred to as the Paiute Shoshones. an extensive ditch irrigation system for irrigating the wild

The Owens River valley had been the home of the Paiute Indians for many years; Linguistically, these Indians spoke the Shoshone language and are sometimes referred to as the Paiute Shoshones. They were primarily food gatherers and farmers. They lived on Pinyon Pine nuts,[8] wild hyacinth tubers and yellow nutgrass tubers as well as the larva of a fly that laid its eggs upon the surface of saline Owens Lake. They also lived on deer, Desert big horn sheep, fish and small game. They had built an extensive ditch irrigation system for irrigating the wild hyacinth and yellow nutgrass.[9]

Ephydra hians

We find the daily life, culture, and customs of the Paiute both fascinating and compelling. Should you wish to learn more about the Valley, its peoples, and history, please check the section “Additional Readings and References” at the end of this story. We want to tell you about one item in the Paiute diet which we had never heard of in any other Native American peoples’ culture.

“One of the most Interesting foods of the Indians of the Intermontane-Plateau was kuteavi, the larva of a small fly (Ephydra hians) which was to be found from northern Nevada to Mono Lake on the eastern border of California.”

The larva was exploited for food. ”… Among the earliest references to kutsavi collecting at Mono Lake is that of Zenas Leonard in 1833. The water in this lake becomes stagnant and very disagreeable — its surface being covered with a green substance, similar to a stagnant frog pond. In warm weather there is a fly, about the size and similar to a grain of wheat, on this lake, in great numbers. … When the wind rolls the waters onto the shore, these flies are left on the beach — the female Indians then carefully gather them into baskets made of willow branches, and lay them exposed to the sun until they become perfectly dry, when they are laid away for winter provender..”[10]

Conflict With The Settlers

While the Paiute lived quietly in the Valley and mountains for centuries, it took only a few years for their way of life to be changed forever. .

“In the 1860s, discovery of gold and silver in the Sierra Nevada and Inyo Mountains attracted a flood of prospectors. Ranchers and farmers followed, often utilizing Paiute irrigation systems and grasslands. A harsh winter and scarce food in 1861-1862 forced the Paiute and settlers into open conflict. The military intervened and, in 1863, forcibly removed 1,000 Paiute to Fort Tejon in the mountains south of Bakersfield.

Many Paiute eventually left Fort Tejon and returned to the Owens Valley where they lived in camps near towns and farms. They integrated farm and domestic labor with traditional food gathering, and by 1866 were indispensable to the Owens Valley’s agricultural economy.”

Photograph of .92” Japanese marble courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia

Photograph of .92” Japanese marble courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia

A Little Bit About Manzanar Camp

As we noted above, the National Park Service sees Manzanar as typical in many ways of the other nine camps in the Continental United States.

The United States Army, which supplied Military Police[11] to the Camp throughout the War, leased 6,200 acres from the city of Los Angeles to build the camp. In June of 1942 the War Relocation Authority (WRA) took over operation of Manzanar from the U.S. Army.

Manzanar Was Similar In Many Ways To The Other Internment Camps

Like in the other camps the internees at Manzanar built gorgeous gardens. Each garden, whether small or large, functional or ornamental, contained ideas and design elements which reflect the rich history, culture, and essence of the Japanese Americans. They expressed themselves in their gardens.

Also like in the other camps the internees slowly began to resolve their differences internally. In many aspects they governed themselves inside the Camp including the resolution of conflict and disagreements.

The Manzanar internees published a newspaper in English and, sometimes, in Japanese. The Manzanar Free Press published its introductory edition on April 11, 1942. We wonder who named the paper and how the name was chosen.

The Library of Congress has pulled together twenty-nine Camp newspapers in Japanese, English, and both from Internment Camps in seven states. The Manzanar Free Press is included in this collection.[12]

Unique And Unusual Things About Manzanar Internment Camp

Marbles were made in Japan as early as the 1920s and we note in our story “Amache Marbles” (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/amache-marbles/) that some of the Japanese American children who were incarcerated may have had access to Japanese marbles like this gorgeous example.

Photograph of Red and White Pincher With Black; Photograph of a Japanese marble courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia[13]

Photograph of Red and White Pincher With Black; Photograph of a Japanese marble courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia[13]

So, like at Amache and in other Camps, it is probable that the children in camp had access to both Japanese and to American marbles.

However, there are a number of things about Manzanar marbles which are unique. While researching online we met Jeffery Burton, Cultural Resources Program Manager and Park Archeologist at Manzanar National Historic Site. We introduced him in the opening paragraphs of this story. Jeff wrote to us on Academia.edu and he told us “We found over 300 marbles at the Arai Pond and [again] at Children’s Village.” We were astounded! Six hundred marbles dug in one camp? We have researched and volunteered on archaeology dig sites for over twenty years. We have also published a number of stories about the archaeology of childhood (“Invisible Chrildren” https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/invisible-children/). But we have never heard of so many marbles found on one site!

Glass. Orange/clear (6 marbles) 1.5 cm, Blue/clear (3 marbles) 1.5 cm, Green/clear (2 marbles) 1.5 cm, Yellow/clear 1.5 cm, Dark amber 1.5 cm, Light amber 2.2 cm

Manzanar National Historic Site, MANZ 7573[14]

Manzanar Marbles

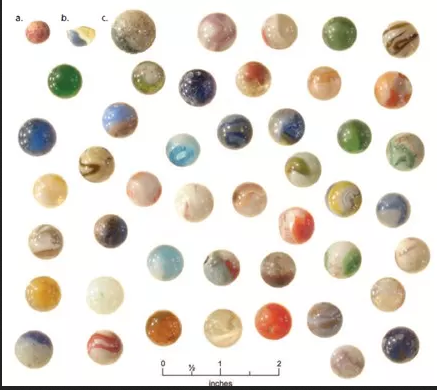

The caption which accompanies this photograph of marbles found at Manzanar reads: “Marbles Almost everyone who was a child at Manzanar remembers playing marbles, and when they played, they played for keeps. Some children amassed collections of hundreds of marbles”

Examine these marbles dug at Manzanar carefully. While we don’t see it identified in the caption, the marble on the bottom row, far left, is a flower China. This one was found during excavation at Shepherd Ranch, which was also part of Manzanar. The ranch was used as a picnic area during the internment. We can only see one side and what looks like a red double helix around the hemisphere; the other side of the marble probably has a matching flower. As Block,[15] explains, It is a bird’s feet or a helix pattern. It can be hard to research these antique Chinas, but it may date to the mid-1900s or to the Victorian Period. It was an antique when it arrived at Manzanar and no child bought this one at a nearby dime store. We have never seen another that was dug on an archaeological site.

We shared this photograph with our Japanese expert and Japanese glass marble collector Josh Bates and we asked him if he saw any Cat’s Eye marbles in this lot.

American collectors have been told in reference books, at marble meets and swaps, on sanctioned digs, and, of course, online, that true Cat’s Eyes were introduced after World War II. Josh was just as unsure whether or not the lot has a glass Cat’s Eye as we are.[16]

The marble on the far right looks to us like a handmade German double naked core swirl. However, there is a touch of red in the glass as well.So this marble does not look like a machine-made marble to us. The orange and red on the bottom do look like Cat’s Eyes.

Shiroaiko

As we conducted this research on Manzanar marbles we simply did not know for certain when the Japanese manufacturers introduced the Cat’s Eye, like the wavy four vane red, bottom right in the photograph, and the orange, bottom row right. The question was simple: could the Cat’s Eyes found at Manzanar be from before 1942 and could they have been made in Japan?

We found the absolutely certain answer online in the Forum All About Marbles. Check the threads “Matsuno, the only survivor in Japanese marble industry” and “1938 Isogami Cat’s Eye patents.”

Shiroaiko tells us that Japan’s marble production was 1,500 tons in 1940, then dramatically decreased to 400 tons in 1941. This means that export to countries such as Great Britain and the United States stopped.

We learned about the tireless work and exceptional research, on the ground and in the archives, of Aiko Suzuki (User name Shiroaiko). Aiko, of Yamagata, Japan, writes on her profile page:

“I started collecting in 1998 in Sendai [capital city of Miyagi Prefecture], Japan, and visited every shop and antique dealer in the area being listed in a local registry. One day I got a small lot of Yasuda transitionals from a dealer in Miyamachi and my interest in older marbles grew. I spent several months in 2004-5 in UK, studying glass and doing my project at University. It was of course a good occasion for collecting marbles. …” She later authored a marble history book in Japanese.

Aiko knows her glass. She was a lamp worker from 1995 – 2014 and she made a small number of marbles. She sold some of these along with handmade glass eggs, just for fun, in Tokyo, Sendai and other cities in Japan.

Username Aussie, in Victoria, Australia, writes this about Aiko and her research:

“Aiko’s meticulous and extensive research has totally changed/corrected a lot of our (Western World marble collectors) ideas. Without her we could never have worked out these things. Many of our suppositions which had been spread by hearsay were proved wrong. She is a true hero. As an Australian collector I knew we had a lot of old marbles rarely seen in American collections and I now take as much pride in my Japanese marbles as I do in my antique Germans.”

On September 29, 2024, Aiko answered our question about pre-World War II Japanese Cat’s Eye marbles:

Tatsukichi Isogami (1881-1954) applied for two patents for cat’s eye marbles in 1938 (Showa13). The first patent (Showa14-11324 Multi-Color Glass Ball Manufacturing Device) primarily concerns a structure in a tank furnace which is designed to create vanes in a marble matrix, while the second patent (Showa 14 – 6822 Glass Ball Design) deals with the vane configuration, especially how vanes look in a glass marble. Something curious is the first documented use of the phrase “Cat’s Eyes” (Neko-no-Me, 猫ノ目) in the first article, accompanied by the term 通称 which means “also known as” “commonly known as”. Does this imply that the marble type was already known to the glass toy industry at the time of application in May 1938? Or did he just coin the name for the new marbles? Nishiki-dama, the common term for cat’s eye marbles in Japanese, doesn’t appear in the Isogami papers.

Tatsukichi was known to be the head of Japan’s Marble Industry Association, organized in 1935 (Showa10). It is unusual that more than one patent is prepared for one idea. The reason why Isogami had to prepare two was to prevent Naoyuki Seike to make same type of marbles using his own device being submitted to patent office 8 days earlier than Isogami’s Showa14-11324. We have line-to line translation of Isogami articles in “1938 Isogami Cat’s Eye Patents” thread.[17]

Aiko concludes that “My answer to your question is yes. Cat’s eye marbles existed in prewar time. I have pre-war examples of Seike’s Stripey Cats in an original box of pre-war ohajiki (flat marbles) and marbles.”

Photographs Courtesy of Shiroaiko

We were excited to get an answer to a question that had eluded us since we started collecting twenty years ago. The boys in Manzanar may have played with Japanese Cat’s Eyes in California before their relocation, and they may have bought the marbles from local Japanese American shop owners in California.

Just look at these gorgeous photographs. The ones with orange and red vanes look identical to the marbles dug at Manzanar as shown in the National Park Service photograph above. Some of the marbles in this photograph actually look “tipped”. That is, one color, for example white, is tipped in blue and the lavender is mixed with white.

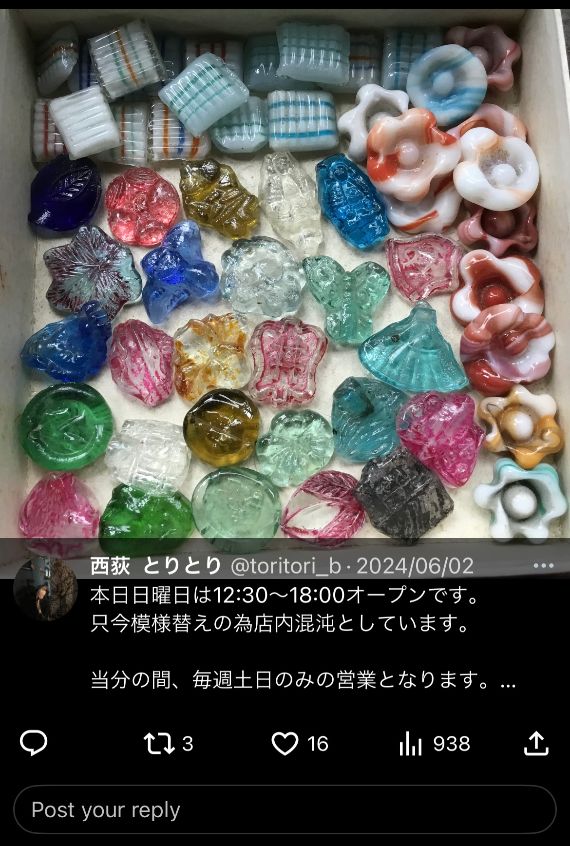

Ohajiki

Along with marbles, pre-war Japanese, and possibly Japanese Americans, loved ohajiki. This traditional Japanese children’s game is very similar to marbles and may be played with glass marbles. This photograph shows an example of ohajiki pieces. Shiroaiko explains that ohajiki is an inside activity for girls. Marbles are an outside game for boys. Aiko also notes that if a boy had a sister(s) in his family, he might play okajibi with them. But as they grew up boys did not like to act girlish and they refused to play. In earlier times like Meiji [1868 –1912 ] or Taishō [1912 – 1926] ohajiki was played regardless of gender.

Jeff Burton mentioned that a few of these pieces were found at Manzanar during the excavation at Children’s Village.

Photograph Courtesy of Takomo Noguchi, Toritori, Tokyo

Aiko: “I have written that there were more ohajiki collectors than marble collectors in my country. Especially pre-war flat marbles are fascinating for their varieties. I got a permission to share a screenshot of Toritori’s [Tori Tori] instagram post with you. Toritori is one of the antique shops in Tokyo, where ohajiki fans go and buy ohajiki and other things of curiosity. The shop owner also sells my marble book at the store.”

We would be fascinated to learn whether or not archaeologist have found ohajjiki at Manzanar. They must have, but we can only imagine that they had no idea what they were unless a Japanese American volunteer or staff member could explain it to them.

Photograph Courtesy of Shiroaiko

Here are the Seike’s Stripey which Aiko mentions above.

“The box is called giya-bako, meaning giyaman (diamante) box, which was used to house toys in pre-war time. Glass-lid boxes make a good presentation, making themselves kind of special. Much older time like in Meiji (1868-1912) or Taisho (1912-1916) periods, even entirely glass-covered boxes existed. These were the time glass was valued. In this example, the glass part is only the lid. Other components of the box is card board paper, being bound by glued paper strips. The glass marbles were insulated by paper shreds. … Stripeys are known to be made by Naoyuki Seike, because the marbles Naoyuki left for his family included one. One yellow 4-vaned cat’s eye is also Seike’s. The vanes are thicker than other Japanese makers’. Thestyle of flat marbles is also thought to be pre-war and the maker is unknown. They are not machine-made ohajiki. It could be Seike, but there is no document that I could find which supports Seike also made ohajiki. He was rather a marble maker for export.”

All of these marbles and ohajiki illustrate in all capital letters that the children of Manzanar had marbles and that, regardless of barbed wire, guard towers, Military Police, internal strife, icy winters and wet summers, they played marbles. Just like in wars which we have studied, in times of peace and expansion, in the old West, and even in dire poverty, children have continued to play with marbles or round cobble stones since the beginning of time.

Manzanar National Historic Site, National Park Service

Children’s Village & Arai Pond

When Jeffery Burton told us that 600 marbles were found in these two locations of the Camp, we were determined to learn more about them.

“In an old pear orchard, 101 American-born children ranging from newborns to 18 year olds lived in the Children’s Village, the only orphanage in any war relocation center. Living in three specially-built barracks and nurtured by a dedicated Japanese American staff and others, they became a unique wartime family. Nearly half had been brought from west coast institutions and foster homes. Others were temporarily separated from families when their parents were arrested or became ill or were infants born to unwed mothers.”

Some of these marbles were found in the Children’s Village while hundreds were found in the Arai Pond. The the marbles in the pond were thrown in by Arai’s four children, and not by the orphans. Some of them are fascinating to us. For example, look at the ribbon swirl in the upper right of the photograph. If American, which company might have made it? We think that there is another one like it to the left about four marbles down. Could it be a Japanese “Stripey” like the ones Airo told us about?”

Children’s Village was landscaped with lawns, flowers, and cherry trees. Japanese American staff built playground equipment and furniture and collected money for toys and other items, while some Owens Valley neighbors brought freshly-baked cookies and clothing. The children made friends through camp schools, churches, clubs, and sports and even formed their own baseball team.”[18]

And, based on all the marbles found, they certainly played marbles. A lot!

Arai Pond

This pond was a labor of love for Internee Hanshiro Arai.

“In a 2006 oral history interview, Madelon Arai Yamamoto mentioned her father, Hanshiro (Jack) Arai, had constructed a fish pond populated with koi, perch, and minnows. Mrs. Yamamoto’s description directed archeologists to the area between Block 33 Barracks 3 and 4, where brush, leaf litter, and fallen tree limbs obscured the surface. Staff, students, and other volunteers, including Mrs. Yamamoto herself, eventually unburied the site in 2011.”

The pond also contained water lilies. The water which Mr. Arai used to fill the pond flowed down a narrow channel which he had built, over a small waterfall, “…then into a small pool before dropping to the pond.” When excavated, the volunteers found evidence of a tunnel which Mr. Arai provided “…to give the fish a place to hide.”[19] We certainly wish we knew Mr. Arai’s profession or occupation before his experiences in Manzanar. He was certainly gifted.

Diggin Holes!

Gardening, ornamental landscaping with gorgeous water gardens and agriculture were not foreign to many of the internees. And that’s a good thing because internees dug irrigation canals and ditches, worked and tended the acres of apple orchards and other fruit trees, raised vegetables, chickens[20], hogs, and cattle.

“Japanese Americans who practiced landscaping and gardening in the camps were predominantly Issei with professional experience in farming, landscape maintenance, and horticulture from both urban and rural communities. In 1940, 43% of all Nikkei living on the West Coast were employed in agriculture, and an additional 26% were employed in agriculture-related activities such as produce businesses.”[21]

Speaking simplistically Issei are Japanese Americans born in Japan while their children born in The United States are nisei.

Summing Up What We Have Learned So Far About How Manzanar Was Unique Among All The Internment Camps

We are considering things which were unique to Manzanar and so far we have learned that the Children’s Village was the only orphanage ever opened in any internment camp during the War. While there were ornamental and vegetable gardens in all of the relocation centers, some the ornamental gardens at Manzanar were built and stocked with minnows, trout, and koi by an Japanese Americans with exceptional talent, vision, and dedication. Mr. Hanshiro (Jack) Arai, for example, was an artist who built the Manzanar gardens with determination and grit.[22]

And we learned that an exceptional number of marbles were tossed into Mr. Arai’s ponds by the resident children. No, we have not studied about marbles tossed into all the Internment Gardens, but we cannot imagine that over 600 marbles were recovered by archaeologists and volunteers on any other dig site.

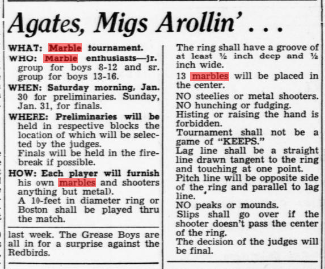

The Manzanar Tournament Marbles

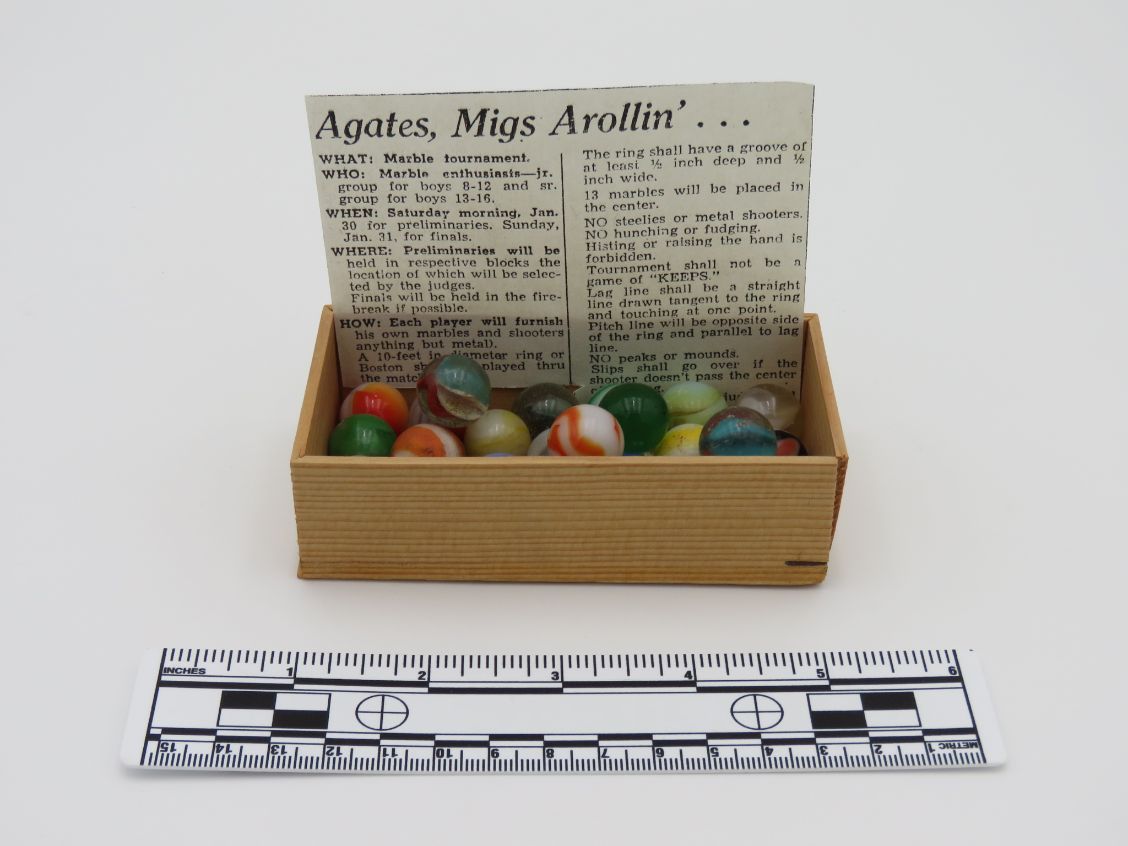

We have spent some time in the digital archives of the newspapers published in the Relocation Centers but this note advertising a marble tournament is the only one that we have seen. A tournament may have been unique to Manzanar.

Photograph is Courtesy of County of Inyo, Eastern California Museum

Heather Todd is Curator at Eastern California Museum in Independence which is only about six miles from Manzanar. She is very knowledgeable and informed about Inyo and Camp history and artifacts and we shared emails and had a long telephone conversation about marbles at Manzanar. This notation about the marbles is included in the gallery display at Eastern California Museum[23]:

Description

This is a collection of 23 marbles in various colors. Likely found at Manzanar. They are housed in a small wooden box. With them is a photocopied article titled, “Agates, Migs Arollin’…” about a marble tournament held for boys at Manzanar War Relocation Center. Collection Shiro and Mary Nomura Collection Entry/Object ID 1994.80.68

The photograph of this box, like the marble images provide by the National Park Service, is very interesting. Note that the artifact description reports that the marbles were “likely” found at Manzanar.

And, of course, both “Shiro” (白) and Nomura (野村) are both Japanese names. We did not ask Heather about the contributors of the marbles because we did not want to intrude on the couple. But it is probable that one or both of them may be direct descendants of internees at Manzanar. This means, of course, that the marbles may have been passed down through one or more families .And if this is the case then the boy who won the marbles may have placed them in his “trophy box” himself.

The Marble Tournament[24]

Manzanar is not the only Camp to have a marble tournament. Amache had one as well. However, we had a good laugh with Heather when we read the date of the planned Manzanar tournament!

We searched the digital archives to find the original story and print it because it is easier to read than in the clipping in the marble box.

The tournament was planned for January 30th 1943. Outside. Finals were planned for the next day in the “firebreak if possible.” In January 1943 the average temperature in Inyo County was 43.20°; the coldest it got was 30.90°; the warmest was 55° and the Camp got 3.71” of rain that month![25] We agree that this is not bitter cold, but it is cold and wet and hardly a time of year to be playing in a marble tournament outside.

February was drier with only .88” of rain and a bit warmer. The average temperature was 46.70 and the coldest day was 34.10°; the warmest was 59.20°. Better, but still chilly to be playing marbles.

Photograph of a Japanese marble courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, West Virginia

And besides, the boys had to practice before the tournament. How could they if most days were very chilly and damp?

One thing that we found odd about the story is the title. Why did the writer use the word “Migs”? We asked Heather about this and she is as confused as we are. Did he or she mean “mibs”? Mibs has been used to mean “marble” since at least the mid-19th century, but if you check online you will see it applied to everything from a playing marble to a shooter, and even the marbles the player shoots at. One thing is consistent: in all three stories published about the tournament the word “migs” is used to describe the marbles.

The rules are straight forward: the tournament is not “for keeps”; no hunching or fudging; no Cannon Balls like those made by The Steele Company in Hopkins, Minnesota. But there is something else you could not do in the tournament: you couldn’t “hist” nor raise your hand!

Well, hist is actually an appropriate word! It means to say something to attract attention or “as a warning to be silent.”

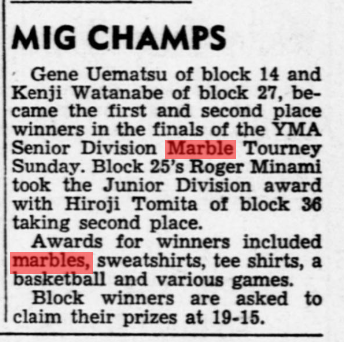

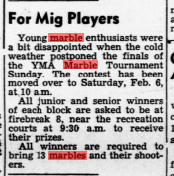

Postponed? Why?

While it is a bit confusing to us, it is apparent that the cold weather pushed the finals forward to February 6th. Note that the sponsor of the Tournament was the Young Men’s Association. At Manzanar, the YMA was a social organization centered around wrestling and judo.[26]

Well, it did finally happened on February 6th. We hope everyone had fun and we also hope that the organization and governance of the YMA was made up of the Japanese American internees themselves.

A Special Find

We have concentrated on marble play at Manzanar in this story. But check out this picture. While conducting our research we found this photograph of an Akro Agate Company Chiquita cup and saucer. This saucer has a turned up rim and we believe it to be a concentric ring type rather than a Chiquita. Since the cup and saucer are different colors the two together are called a gypsy set. Akro Agate boxed and sold gypsy sets with pieces of the same type sold in different colors.[27]

The End Of The Beginning: Mr. Jim Matsuoka’s Lost Marbles

“When it was time to go, I couldn’t bring my marbles. I couldn’t take them with me, so I dug a hole,” he says. “I had two gallon cans full of Victory marbles. Now, they are artifacts of children in Manzanar.” {Interview with Mr. Matsuoka, an Octogenarian when the dig was underway; deceased in 2022}.

We started this story by describing how Mr. Matsuoka was in Manzanar when he was a child. When he was relocated after the War he was unable to take his hard-won marbles with him. But he knew where he buried them! And although in his eighties at the time of the dig, he remember those marbles that he won in Manzanar.

Photograph of Japanese Marbles Courtesy of Josh Bates, Jacksonburg, WV

We noted above the 2017 archaeological investigations which were conducted in Block 11 at Manzanar. Block 11 was Jim’s home in Camp and it was near here that he buried the marbles. The purpose of the 2017 archaeological dig was to recover the marbles as part of a documentary project by artist and social activist Kyoko Nakamaru.

Certainly the dig was conducted by trained archaeologists, National Park Service staff and administrators, and volunteers, and each phase of the dig was planned and conducted with skill, patience, and precision. But the story “The Hunt for Jim Matsuoka’s Marbles…” reads more like a treasure hunt than a formal archaeology dig!

As we have learned in this story, marbles were extremely popular in camp and evidently were the most preferred toy for the boys.

“In fact, marbles are the most common toy recovered at Manzanar. Several former internees tell of burying their marbles, but most could not provide additional information about where they were buried. One former internee said he concealed his marbles all over camp when he left” (Page 3).

As noted, Jim’s family lived in Block 11, Barracks 6, Apartment 2. The fact that he had buried his collection in large cans indicated that they might be found with a metal detector.

We know that after some of the Camps closed in 1945 local citizens salvaged wood and other items from the site. After the closure at Manzanar the buildings were dismantled and removed. The barracks, even the gardens, were often bulldozed.

Still, the water faucet and a concrete entrance to Barrack 6 could still be seen or determined by the dig team.

The Hunt for Jim Matsuoka’s Marbles: Excavations at Block 11, Barracks 6, Apartment 2, Manzanar National Historic Site , 2018 NPS

The Hunt for Jim Matsuoka’s Marbles: Excavations at Block 11, Barracks 6, Apartment 2, Manzanar National Historic Site , 2018 NPS

Since Jim buried the marbles in metal buckets, metal detectors were first used as well as a T-shaped metal probe. Sadly, no buckets of marbles were ever found. Eight marbles were found, but the most common artifacts included in the 510 collected were nails! Still, this was a wonderful dig and we are left to wonder. Where did Jim’s marbles go?

Manzanar Remains

Manzanar is back from the brink. There are visitors now to the National Historic Site managed by the National Park Service. There are tours, a visitors center, a park store, and you are encouraged to volunteer to work on and to donate to the site. There is a very active Junior Ranger program.

And don’t forget about Eastern California Museum in Independence. The staff there are extremely knowledgeable and will be happy to answer questions about Inyo County, the Owens Valley, Independence, and, of course, Manzanar. There is also a Manzanar exhibit at the Museum.

What happened at Manzanar should never have happened to American citizens in the United States. Manzanar now stands as both a survivor and a beacon. We can never let it happen again.

Additional Readings and References

Bettinger, Robert L. “Native Land Use: Archaeology and Anthropology.” From the book Natural History of the White-Inyo Range, Eastern California

https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520319509-017/ . https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1525/9780520319509-017/html?lang=en 9/25/2024

Burton, Jeff, and Mary Farrell. “Creating Beauty Behine Barbed Wire Manzanar’s Japanese Gardens” Pdf

Eastern California Museum, Independence, CA. Gorgeous photographs on their website, wonderful collections in the Museum, and friendly people. We sure do wish we could visit! https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=Eastern+California+Museum 9/25/2024

Finlay, Mark R. “Behind the Barbed Wire of Manzanar: Guayule and the Search for Natural Rubber.” November 3, 2011. Distillations Magazine. Science History Institute Museum & Library. @ https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/behind-the-barbed-wire-of-manzanar-guayule-and-the-search-for-natural-rubber/ 10/6/2024

Guayule. Ferguson, W.W. “These Tiny Plants May Prove a Salvation.” Daily News (Los Angeles) 8 May 1942, page 3. “Japanese [American] nurserymen [at Manzanar] will have a part in what many persons believe to be the most remarkable agricultural revolution since the cotton gin.”

https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/manz/exb/Camp/past_times/MANZ7573_marbles.html

Independence, California. Founded in 1861 as a gold rush mining town. The town covers about three square miles and is home to approximately 600 people. https://digital-desert.com/independence-ca/ 9/19/2024

“Interweaving Living Stories and the Unburied Past: Community Archeology at Manzanar National Historic Site”. Manzanar National Historic Site https://www.nps.gov/articles/community-archeology-at-manzanar.htm 9/9/2024

“Manzanar Children’s Village” Nevada Ghost Towns and Beyond. @ https://nvtami.com/2024/07/22/manzanar-childrens-village/ (9/27/2024). There are some details in this story which we did not find at the National Park Service.

Manzanar War Relocation Center @ https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/manz/campLife.html/ 9/25/2024

“Nikkei Progressives’ Tribute to Jim Matsuoka” @Nikkei Progressives’ Tribute to Jim Matsuoka – Rafu Shimpo

Owens Lake Massacre. “DWP archaeologists uncover grim chapter in Owens Valley history”. https://www.latimes.com/local/la-xpm-2013-jun-02-la-me-massacre-site-20130603-story.html 9/25/2024

Owens Valley. https://digital-desert.com/owens-valley/#google_vignette 9/25/2024

Owens Valley Indian War. https://digital-desert.com/owens-valley/history/indian-war.html 9/19/2024

Tavoda, McKenzie (2018) “A “Land You Could Not Escape yet Almost Didn’t Want to Leave”: Japanese American Identity in Manzanar Internment Camp Gardens,” Voces Novae: Vol. 7 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol7/iss1/8 10/1/2024

The Owens Valley Paiute. https://mojavedesert.net/owens-valley-paiute-indians/ 9/19/2024

Walser, Lauren, “Restoring the Historic Japanese Gardens of Manzanar,” November 2, 2015. National Trust for Historic Preservation @ https://savingplaces.org/ 9/27/2024

- Special thank you to Jeffery Burton, Cultural Resources Program Manager and Park Archeologist at Manzanar, California, National Historic Site. Burton, Jeffrey F. and Mary M. Farrell. “The Hunt for Jim Matsuoka’s Marbles Evacuations at Block 11 Barracks 6, Apartment 2” Manzanar National Historic Site. 2018. Available at Academic.edu ↑

- Adams, Ansel, photographer. Entrance to Manzanar, Manzanar Relocation Center / photograph by Ansel Adams. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2002695960/ 9/17/2024 ↑

- There were ten camps in the Continental United States. Honouliuli camp in Hawaii played a unique role. Hawaii was a United States Territory in 1941 and it was placed under martial law throughout the War. Honouliuli served as an Internment Camp “…US citizens and residents of Japanese and European ancestry arbitrarily suspected of disloyalty following the attacks on Pearl Harbor…. Run by the U.S. Army and opened in March 1943, Honouliuli was both a civilian internment camp and a prisoner of war camp with a population of approximately 400 internees and 4,000 prisoners of war over the course of its use.” https://www.nps.gov/hono/learn/historyculture/index.htm 9/19/2024 ↑

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Japanese-American-internment 9/19/2024 ↑

- https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/historyculture/japanese-americans-at-manzanar.htm 9/19/2024↑

- Chalfant, Willie Arthur. The story of Inyo. [Chicago The Author, 1922] Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22011596/>. 9/24/2024 ↑

- https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/historyculture/people.htm 9/22/2024 ↑

- In Willie Arthur Chalfant’s book The story of Inyo, noted above, the author provides a wealth of information on Paiute diet and the gathering of piñon or pine nuts. Check the start of Chapter III “Native Customs” page 14. We lived in the Middle East for several years and pine nuts were both inexpensive and commonly used in food. We found then delicious and we always enjoyed them in rice and many other dishes. ↑

- https://digital-desert.com/owens-valley/history/indian-war.html 9/19/2024 ↑

- Z. Leonard, Adventures of Zenas Leonard, Fur Trader and Trapper, 1831-1836. Edited by W. F. Wagner. The Burrows Brothers Co. Cleveland, 1904, p. 166. Possibly Leonard is referring to Owens rather than Mono Lake. At any rate, the account does not refer to Humboldt Lake as some including myself, have thought previously, the proof resting in the known fact that the Ephdr fly does not breed In Humboldt Lake. Owens Valley is further Indicated by references to pottery and semi-subterranean houses which the Humboldt Lake Paiute did not possess. In Robert F. Heizer, “Kutsavi, A Great Basin Indian Food.” ↑

- “December 6, 1942: ‘Manzanar Riot.’ Military police fire into a large crowd gathered at the police station demanding the release of Harry Ueno, arrested for allegedly assaulting Fred Tayama. Seventeen year-old James Ito and 21 year-old Jim Kanegawa are killed nine others are injured.” Manzanar was certainly not the only Camp where internal disagreements and struggles led the internees into open conflict with the MPs, but it was one of the more bloody. Shots were fired by the MPs after rocks were thrown at them and at the Military Police station by members of a crowd (“mob”), and the MPs responded with “tommy gun” (Thompson submachine gun), shotgun, rifle, and possibly sidearm fire.…The “Manzanar Riot” was the “logical outgrowth of pre-evacuation factional conflicts among evacuees, clashes of ideology intensified by war, and the unhealthy condition of accumulating resentments within the limited area of the Center.” Pre-evacuation conflicts “centered chiefly around two fairly distinct and identifiable groups.” The conflicts were “a curious mixture of pre-war personal feuds, political, business and social rivalries of long standing.” Evacuees “from Southern California, particularly Los Angeles, carried these conflicts into Manzanar in March, April and May, 1942.” When the smoke cleared, aBoard of Officers “absolved” the military police of any malpractice or violation of orders during the riot at Manzanar because the men believed they were in personal danger.” Remember, other than stones, the Japanese Americans were unarmed. This is the fire power available to the Military Police: Weapons issued to the military police company at Manzanar, … included “four light machine guns,” “two heavies,” “eighty-nine shot guns,” “twenty-one rifles (Enfield),” and “twenty-one tommie guns.” There are two detailed documents available for review online which detail the roles of the Military Police in Camp daily life and at the riot on December 6, 1942. You can read about the Riot and the role of the MPs in detail in: Manzanar Historic Resource Study/Special History Study. “Chapter Eleven: Violence at Manzanar on December 6, 1942: An Examination of The Event, Its Underlying Causes, and Historical Interpretation” @ https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/manz/hrs11c.htm (9/25/2024). You might also want to read Manzanar Historic Resource Study/Special History Study. “Chapter Thirteen: The Role of The Military Police Providing External Security For the Manzanar War Relocation Center” @ https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/manz/hrs13c.htm 9/25/2024 ↑

- https://www.loc.gov/collections/japanese-american-internment-camp-newspapers/about-this-collection/ 9/25/2024 ↑

- To see some other Japanese Pincher marbles check https://www.allaboutmarbles.com/viewtopic.php?t=48150 9/27/2024 ↑

- @ https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/manz/exb/Camp/past_times/MANZ7573_marbles.html 9/26/2024 ↑

- Stanley A. Block. Marbles Beyond Glass. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2006, pps.86 – 87 & 108 – 109. We also suggest that you check Paul Baumann. Collecting Antique Marbles Identification and Price Guide, 4th Edition. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2004, pp. 34-35, and Everett Grist. Antique & Collectible Marbles Identification & Values, 3rd Edition, p. 39. ↑

- You might want to read about some 1955 Japanese negotiations in Japan between Marble King, Inc. and Japanese marble makers in Japan in Six, et.al., page 94. Dean Six, Susie Metzler, and Michael Johnson. American Machine-Made Marbles Marble Bags, Boxes, and History. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2006. ↑

- For Showa14-11324: https://www.j-platpat.inpit.go.jp/c1800 … CE74/22/ja 10/4/2024 ↑

- Manzanar’s Children’s Village Manzanar National Historic Site @ https://www.nps.gov/places/manzanar-s-children-s-village.htm 9/27/2024↑

- “Interweaving Living Stories and the Unburied Past: Community Archeology at Manzanar National Historic Site” Manzanar National Historic Site 9/27/2024 The photograph on this page is from the section “The Beauty That Remains” in this story.↑

- “Japanese Americans at Manzanar.” @ https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/historyculture/japanese-americans-at-manzanar.htm/ 9/29/2024↑

- https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gardens_in_camp/ 9/29/2024 ↑

- We recommend that you read Jess Burton and Mary Ferrell’s story Burton, Jeff, and Mary “Creating Beauty Behind Barbed Wire Manzanar’s Japanese Gardens” ↑

- Where you can find the original exhibit: https://hub.catalogit.app/9821/folder/entry/80dce680-83a0-11ed-927e-0d077af76f18 ↑

- “Agates, Migs Arollin’…” from Manzanar Free Press (Manzanar, CA) 23 Jan 1943, page 4. Rettived from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn84025948/1943-01-23/ed-1; “For Mig Players” from Manzanar Free Press (Manzanar, CA) 3 Feb 1943, page 4. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn84025948/1943-02-03/ed-1; and “Mig Champs” from Manzanar Free Press (Manzanar, CA) 10 Feb 1943, page 4. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn84025948/1943-02-10/ed-1 ↑

- Inyo County, California Weather Data | thecalifornian.com 10/2/2024↑

- From Appendix 20 of the Final Report: Manzanar Relocation Center Vol. 1. You can browse or read the entire report @ https://oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt0b69n45v;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=d0e2595&toc.id=d0e818&brand=calisphere==harry%20truman. 10/3/2024

- We were excited to find this cup and saucer at the Virtual Museum Exhibit, Manzanar Historic Site, National Park Service @ Manzanar National Historic Site (nps.gov) (10/3/2024). We recommend that you browse this site: “Pastimes” has gorgeous crisp images of toys and the page is very informative. Information regarding this photograph: Toy Cup and Saucer, c 1940s, Made by Akro Agate Company,

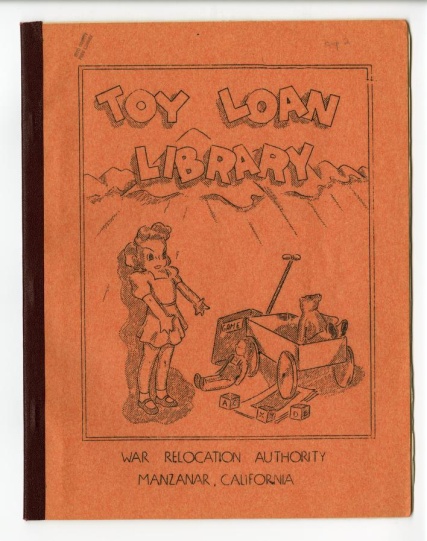

Children brought toys to camp or purchased toys through one of the popular mail-order catalogs. Children also had access to toys and games through the Toy Loan Center, Glass. Cup: H 3 Dia 4.8 cm; Saucer: H .3, Dia 7 cm Manzanar National Historic Site, MANZ 2265 Photo of Toy Loan Library cover: Internet Archive @ Toy loan library : United States. War Relocation Authority : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive 10/3/2024 ↑