“Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.”

– Albert Einstein

All or Nothing

Is nothing something? Does nothing mean something? These two questions have served as the basis for study and debate, including at the post-graduate level, for millennia. Scholars in both philosophy and physics carry on the study, and the debate, today.

We started thinking about nothing and the lack of something recently when we first learned about the prison art of Private John Jacob Omenhausser, CSA.

Déjà Vu all over again

When we studied Omenhausser’s prison art work online at University Libraries, University of Maryland Digital Collections [1] we had a strong sense of déjà vu. We thought immediately of the prison art of Private John G. Gisch, CSA. We studied, researched, and then wrote about Gisch in Chapter Seven “Louse Racers & Ring Taw? Marbles & The Civil War” in The Secret Life of Marbles (pages 150 – 171).

While some of Gisch’s art is in private hands, his known portfolio is remarkably slim. However, he sketched the Main Avenue at Rock Island Prison (where he stayed from 1863 – 1865), which shows men playing marbles. We published both the sketch and a detail of that watercolor in Chapter Seven.

Alike Yet So Different

John Omenhausser was born in 1832 in Philadelphia to German-born parents. John Gisch was born in 1838 in Germany. Gisch immigrated to America and joined the 24th Alabama Infantry in August 1861. Omenhausser joined the Virginia 59th Infantry in April 1861.

We detail Gisch’s service in The Secret Life of Marbles. Omenhausser’s service was honorable and he was a good soldier. Shortly after joining the Confederate Army Private Omenhausser was transferred to the Richmond Light Infantry Blues. His Brigade “…wandered all across the South and only rarely smelled gun smoke in any volume.”[ii] While Gisch was taken prisoner only once, Omenhausser was captured twice.

The first time was less than a year after he joined. It was on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, which is only about 140 miles from Richmond. He became a POW on 8 February 1862 but he was paroled about two weeks later.

When Omenhausser was taken prisoner again on 15 June 1864 the days of prisoner swaps was long over. He was wounded and then taken prisoner at Petersburg which was the longest Military Campaign of the Civil War. There were some 70,000 casualties in over nine months of engagement at Petersburg.[2]

Omenhausser sent to Point Lookout POW Camp

Sent from Petersburg to the new Point Lookout POW Camp in Maryland, Private Omenhausser finished the War there. He was discharged on 9 June 1865. In Chapter Seven we write that Gisch was taken prisoner in November 1863 at Mission or Missionary Ridge where his Regiment fought, and twenty-five died, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign. Private Gisch was shipped to Rock Island, Illinois where he was discharged after the Civil War ended.

As noted, Omenhausser was an inexhaustible watercolorist while in Point Lookout. Much of his Civil War art (including the one with men playing marbles below) still survives in private collections and in nine institutions. The University of Maryland Libraries holds the largest collection of his art (his sketchbooks from Point Lookout). But, like Gisch, “perhaps more Omenhausser art is still out there and waiting to be discovered and attributed to him.”[ii]

Civil War prisoners depicted playing marbles in Omenhausser’s art

While Gisch sketched only a tiny fraction of what Omenhausser accomplished, he often painted scenes for the guards and we know that he sold some of his work while still a prisoner. So, like Omenhausser, Gisch watercolors are still out there for discovery.

“I Am Busy Drawing Pictures”

In 2014 Friends of the Maryland State Archives published I Am Busy Drawing Pictures: The Civil War Art and Letters of Private John Jacob Omenhausser, CSA which was co-authored by Ross M. Kimmel and Michael P. Musick.[i]

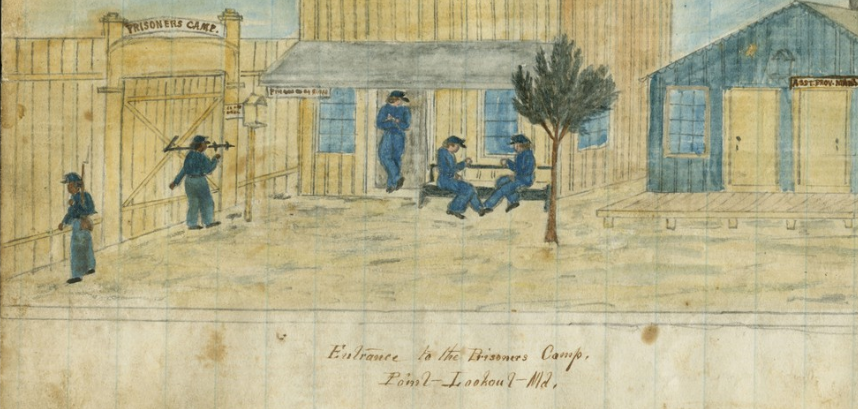

“Among the artist’s more poignant renderings are many depicting the strained and sometimes violent relations between the prisoners and the African American Union troops sent to guard them.”[ii]

Just as an aside, when Omenhausser was taken prisoner the second time in Petersburg, he had faced the Union’s greatest concentration of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). In this sketch of the entrance to the prison there is a black soldier on guard at the gate.

Point Lookout Maryland

There is so much we could say about Point Lookout Maryland. Today it is a state park. During the War it was used as a Union Hospital, fort, and then the Federal’s largest POW camp with some 20,000 prisoners. There is also a mass Confederate grave outside the former prison walls and on the Point.

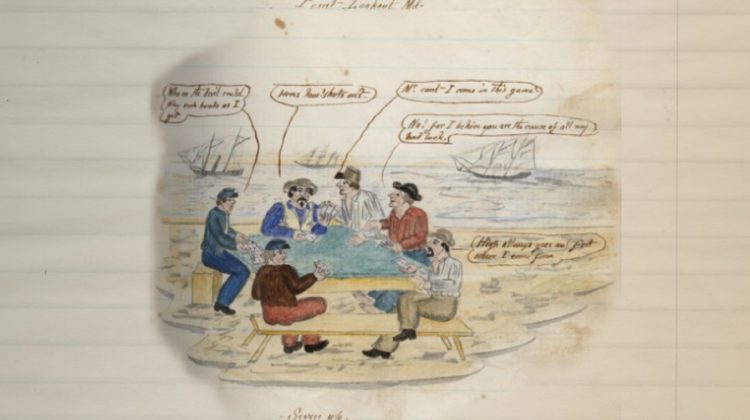

Of course, most of Omenhausser’s sketches depict life on the Point and in the prison. One small stretch of the prison grounds faced Chesapeake Bay and there prisoners used the Bay to bathe, swim, and catch fish and crabs. The first sketch in this post, Seven Up, shows inmates playing cards on the beach. While deprivations and heinous living conditions existed when Omenhausser was an inmate, he seems to have found inspiration from a keen sense of gallows humor.

Not A Copycat!

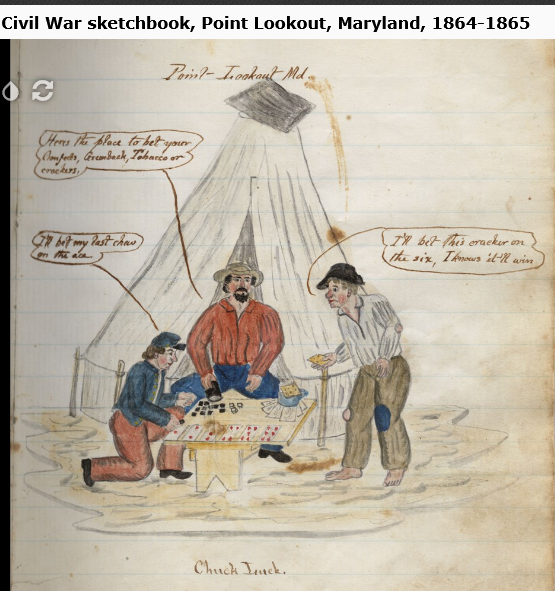

Upon first examination, Gisch’s watercolors look much like Omenhausser’s. However, Omenhausser’s sketches are unique. He drew “cartoons” on most of his sketches! A “bubble” extends from the characters as they speak to each other! Certainly, Gisch never used this technique.

Kimmel and Musick have identified 290 drawings and there are probably more in private hands. Of this portfolio, 278 were drawn at Point Lookout in only one year! Incidentally, in Chapter Seven we identify the local source of Gisch tiny supply box, and we believe that Omenhausser got his art supplies from his family who continued to live in the North. And he needed a large art kit!

Liver Hash

Kimmel and Musick note:

“A striking feature of Omenhausser’s wartime sketches is that nearly all were intended to be humorous, or at least sardonic. This, we think, is unique among large collections of Civil War artists’ work.”

Just one example: in the drawing Liver Hash three men are standing around a large pot with liver in it. All three speak. The man doing the cooking says “Here’s your hot liver hash and bread, only five cents a plate.” A second prisoner, who is eating the hash, reports “Fellows this goes bully.” A third man, who has no hash yet, and who also has a bandana tied over his hat in an odd manner, remarks that “Mr. you ought to give me some hash for catching this grayback off of your hat.”

This one sketch conveys volumes of information. For example, what type liver? Where did the inmates get it? Where did they get the pot? Note that all three have on shoes or boots. All three are dressed well; did the prison not provide or require any type uniform? A grayback (or a blueback) is a louse; lice feature in more than one Omanhausser sketch. By the way, this sketch also features rats. While the cartoon balloons tell us a lot, so much more remains unanswered.

Nothing and Something

Omenhausser captured hundreds of scenes of camp life. He drew men playing cards on the beach; getting a haircut; swimming and bathing in the Bay; playing Keno, which is a lottery or gambling game; cooking and selling crabs and hash; a minstrel-type show (Confederate Variety) in the prison; the prison bakery; school; and hospital, among so many more.

But not one image of men playing marbles. Why? Geisch drew so very few sketches, but one does show marble playing. Omenhausser produced almost 300 watercolors, but not a single game of marbles. Geisch was in prison one year; Omenhausser was at Point Lookout for two.

Omenhausser’s Civil War Drawings: Did they Include marbles?

Jacob Hopkins at The University of Maryland Libraries emailed us that he browsed Omenhausser’s Point Lookout Sketchbook. He found all sorts of games being played

“but none depicting a game of marbles. I likewise didn’t find any mention of marbles in the writings of Omenhausser included in this sketchbook. I also consulted our copy of “I Am Busy Drawing Pictures,” …. This volume includes scans of Omenhausser’s art from collections held at several institutions, including University of Maryland State Archives, Virginia Historical Society, and the American Folk Art Museum. Unfortunately, none of the images published in this book depict a game of marbles…. It does indeed seem odd that Omenhausser painted so many everyday scenes but that a game of marbles was not among them!”

It is possible, of course, that Omenhausser did paint a game of marbles, and the sketch is in a private collection as yet undiscovered by researchers. We know little about either man after the War. We do not, however, have any reason to believe that either continued to paint. Omenhausser died a young man of 44 on 12 June 1877 in Richmond. Gisch was 54 when he died in 1892.

In Conclusion

As we close we return to the beginning. Did Gisch contribute something to the long history of marbles? Yes, he did. He provided the only visual proof that soldiers played marbles during the Civil War. Did Omenhausser contribute nothing to marble history? We believe that both men made a significant contribution. Sometimes nothing really is something!

[1] https://hdl.handle.net/1903.1/4939 1/28/2022

[2] https://www.historynet.com/book-review-finding-whimsy-in-the-grim-business-of-war.htm 1/30/2022

[3] https://www.nps.gov/pete/index.htm 1/30/2022

[4] Jacob Hopkins, Graduate Assistant for Reference, Outreach, and Engagement Maryland & Historical Collections, Special Collections and University Archives University of Maryland Libraries, email to us 25 January 2022.

[5] Kimmel, Ross M. and Michaeol P. Musick. Foreword by Gary W. Gallagher. “I Am Busy Drawing Pictures”: The Civil War Art and Letters of Private John Jacob Omenhausser, CSA. Annapolis:, MD: Friends of the Maryland State Archives, 2014.

Want to read more about marbles?

Your post comparing Private Omenhausser’s art and war experiences to Gisch’s is such a great read. Thank you for including images from the sketchbook in our holdings as well as the quote from me. I am so grateful for the opportunity to share Omenhausser’s sketches with researchers like you and your own audience, as I truly believe keeping these materials alive and accessible is how we will continue to learn more––about Omenhausser and Gisch, about the everyday lives of Civil War prisoners, and about the history of everyday things we take for granted, like marbles.

Jacob Hopkins

Graduate Assistant for Reference, Outreach, and Engagement

Maryland & Historical Collections, Special Collections and University Archives

University of Maryland LibrariesYour post comparing Private Omenhausser’s art and war experiences to Gisch’s is such a great read. Thank you for including images from the sketchbook in our holdings as well as the quote from me. I am so grateful for the opportunity to share Omenhausser’s sketches with researchers like you and your own audience, as I truly believe keeping these materials alive and accessible is how we will continue to learn more––about Omenhausser and Gisch, about the everyday lives of Civil War prisoners, and about the history of everyday things we take for granted, like marbles.

Jacob Hopkins

Graduate Assistant for Reference, Outreach, and Engagement

Maryland & Historical Collections, Special Collections and University Archives

University of Maryland Libraries