Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Have you ever heard of the hand-held dexterity game Three Blind Mice? Neither had we until we checked out the One Source Catalog[1]. After researching the game, and others like it, we realized that while we collected and researched “pin-ball games” and marble-based bagatelle games for years[2], we never stopped to consider that there were marble-based games even before Redgraves’ late 1800s game. The Redgraves bagatelle is an open-top game built to sit on a table or on the bar in a tavern. It has a spring action plunger and is definitely one of the oldest American bagatelle games to use clay marbles rather than steel balls.

The Chicken Or The Egg? The Causal Loop

Three Blind Mice, and marble-based games like it in the late 1800s, were hand-held dexterity games. Dexterity refers to skill and precision in using your hands, fingers, or feet, especially for fine motor tasks. It’s what lets you thread a needle, play a violin, or guide a marble through a maze. Unlike agility (which is about quickness and movement), dexterity is all about control, steadiness, and coordination. Clay marbles were the keys to each of these early games of dexterity and agility.

As we discuss in our story Bagatelle Blues, marble-based pin-ball games require a controlled release in which players use a spring-loaded plunger or cue stick to launch the marble. The amount of force and the angle are critical. Players also need fine motor skills. Unlike free-hand marble games, bagatelle demands subtle wrist control and predictive aiming.

And finally, with bagatelle, there is anticipation and adjustment. Knucklers must estimate how the marble will ricochet off pins or nails, adjusting their launch accordingly.

In short, dexterity is the skill you bring, while reward is the outcome you chase—and marble bagatelle beautifully bridges the two through tactile, strategic game play. While studying Three Blind Mice and other games like it, we realized that marble- bagatelle traces its lineage to nimble-fingered marble-based amusements played in the palm of the hand. We had never considered this idea before!

And games of both dexterity and strategy in the late 19th century led directly to a burst of ringer marble play in the 20th century after the explosion in the American production of millions of glass marbles starting in the late 1800s. Rowdy ringer marble games became as sure a harbinger of Spring as crocus, snowdrops, and daffodils in cities and the countryside all across America.

Trademark & Copyright

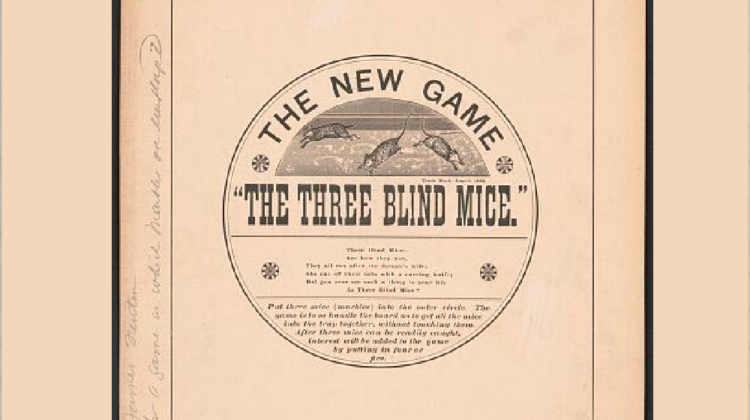

J. Fenton was awarded a trademark for the marble game Three Blind Mice on May 7, 1889. This means that a specific use of the phrase, such as a brand name, logo, product, or service, has been legally registered and protected under trademark law. This doesn’t apply to the Three Blind Mice nursery rhyme[3] itself in general use, but rather to a distinct commercial identity built around that name.

The nursery rhyme “Three Blind Mice” dates back to 1609 in England, but in the U.S., it was copyrighted in various forms well before 1889, including sheet music, children’s books, and later motion pictures.

James Fenton, who was granted the trademark in 1889, did not patent the game. While detailed biographical records are scarce, J. Fenton was likely a toy designer affiliated with a small-scale manufacturer or a novelty company distributor in Buffalo, New York.

‘Round & ‘Round We Go

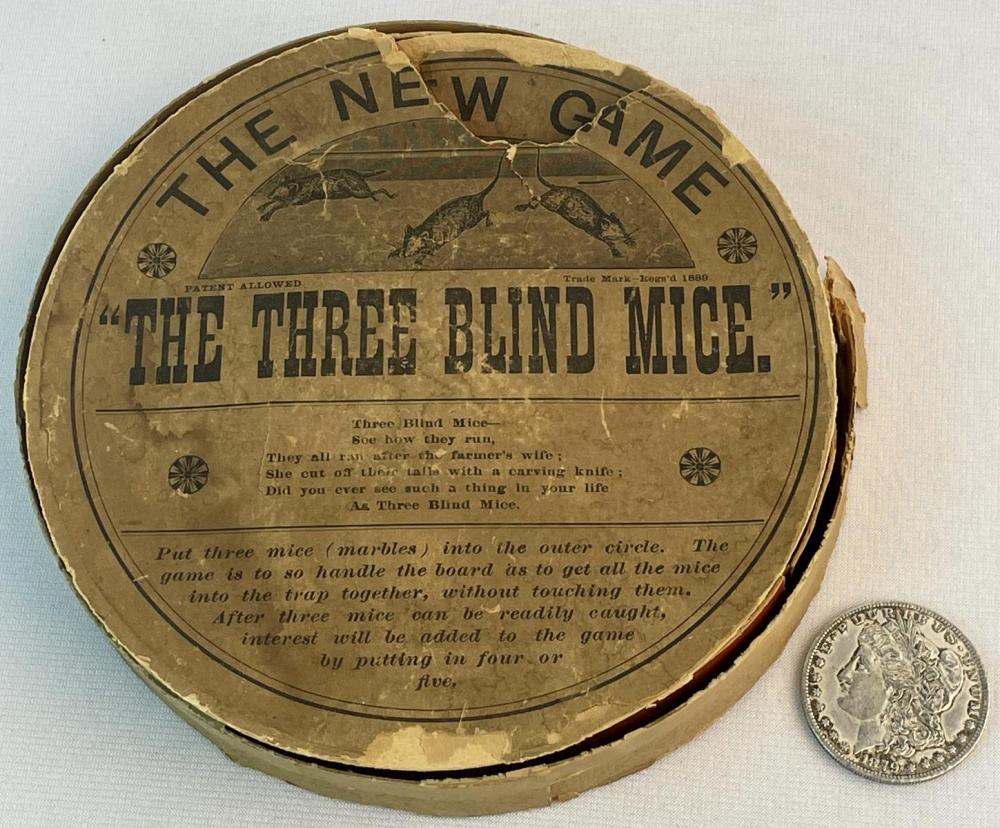

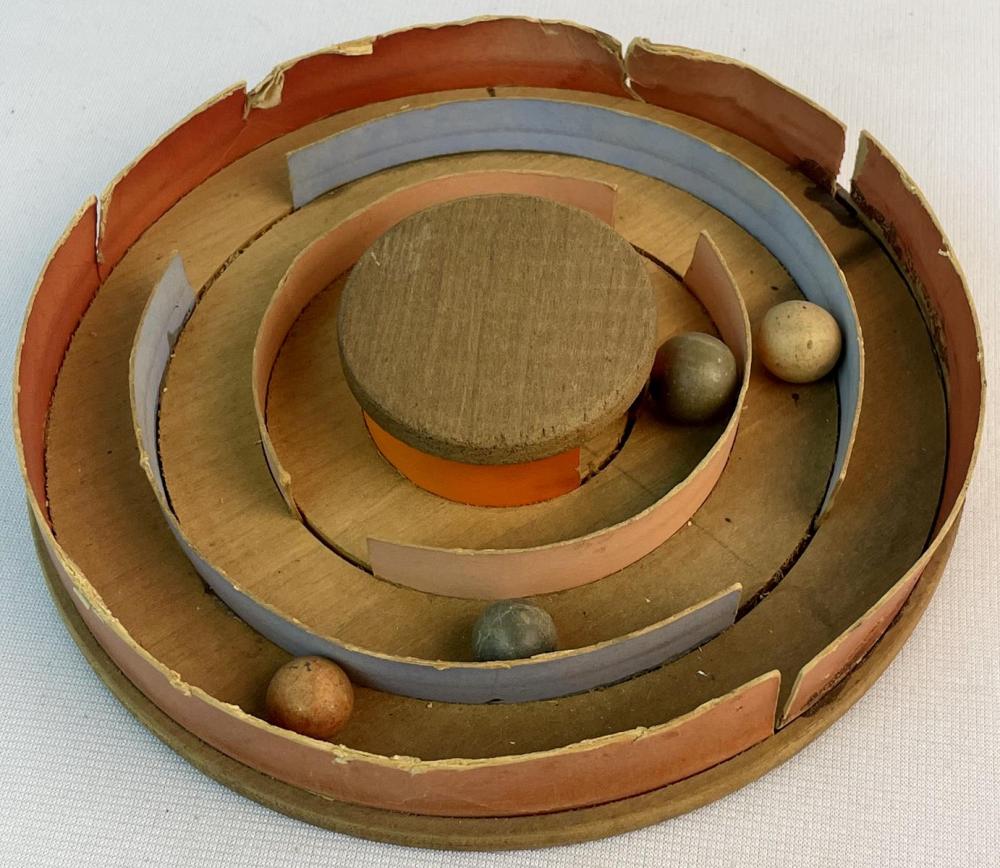

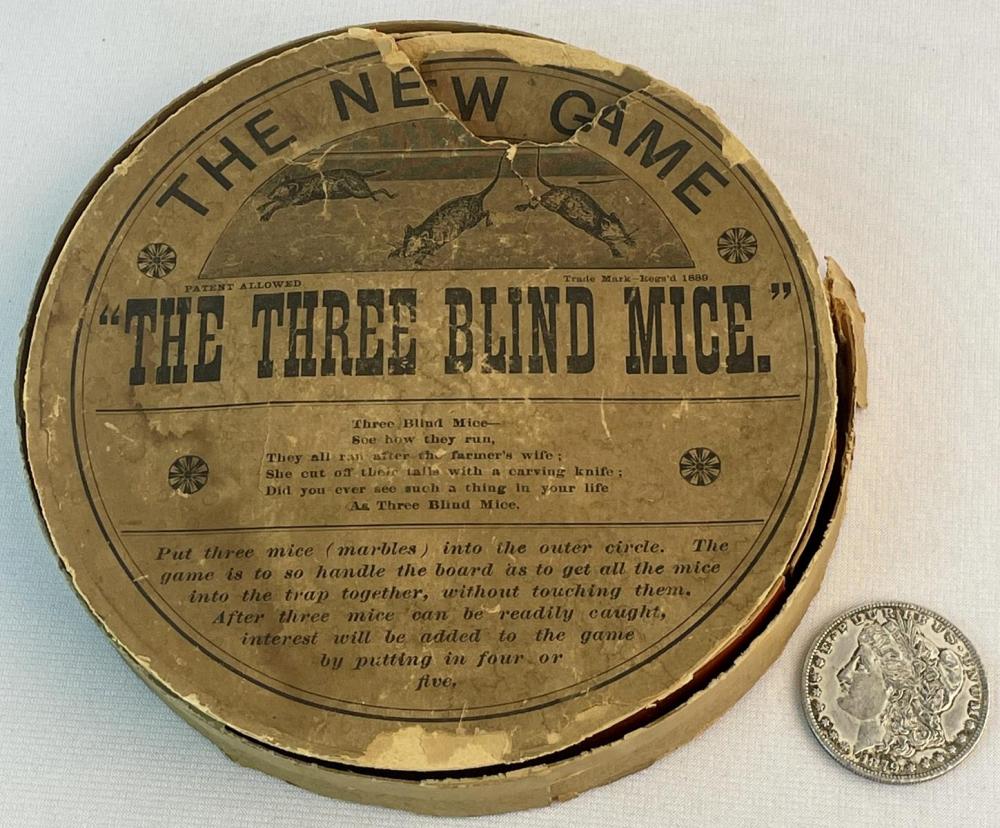

This is a photograph of Fenton’s game of Three Blind Mice. Very simple, isn’t it?

Three Blind Mice Photograph Courtesy, Aaron Rox, Owner One Source Auctions[4]

Fenton’s Three Blind Mice is a handcrafted wooden maze that evokes the spirit of 19th-century ingenuity and tactile play. The concentric circular paths, segmented by alternating orange and blue barriers, reflect both visual rhythm and functional challenge. At its center, a raised platform suggests a goal or symbolic destination, reminiscent of Victorian-era fascination with both puzzles and moral journeys.

Such toys were often made from locally sourced wood and painted with natural pigments. The craftsmanship hints at a time when toys were not mass-produced but lovingly handmade, often by family members or local artisans. The maze’s design may have served dual purposes: entertainment and cognitive development, encouraging spatial reasoning and fine motor skills.

The color scheme, while modern in vibrancy, could be interpreted as a stylized homage to the bold contrasts found in Victorian parlor games and educational tools. The maze’s tactile nature aligns with the 1800s emphasis on experiential learning, where children engaged with physical objects to develop coordination and problem-solving.

Bilbo Catchers & Nine Man Morris

Three Blind Mice was certainly not the only popular dexterity game in late 19th century America. While circular mazes like Three Blind Mice weren’t common in the 1800s, similar puzzle and dexterity toys did exist:

Marble Boards: Some Victorian-era games used boards with holes or tracks for marbles, which may have inspired later maze designs.

Cup and Ball Toss Toys: Popular in Colonial America and mentioned in 1830s publications, these required hand-eye coordination and were precursors to modern skill toys.

Historically accurate sketch of the Victorian parlor game from the imagination of Microsoft Copilot.

Bilbo Catchers: This was a more difficult variant of the cup-and-ball, where the ball lands in a cup on a pointed stick. The Bilbo Catcher, a popular toy in the late 1800s and earlier, was also known by its French name bilboquet.

The name bilboquet comes from French—bille (ball and also the word for marble) and bocquet (little stick or spike). It was widely advertised by colonial merchants and remained a favorite children’s toy through the 1800s. Some versions had a cup on one end and a spike on the other, allowing players to catch the ball either in the cup or on the spike through a hole drilled in the ball[5].

Nine Men’s Morris and Solitaire Boards were popular strategic games often featuring carved wooden boards. Games were sometimes carved right into the home’s furniture! These games used pegs or clay marbles, combining logic with tactile interaction.

Want to hear a folkloric speculation? “’Ulysses S. Grant,’ played Nine Man Morris during the Civil War to calm himself between campaigns.” In truth, as of now, there’s no verified evidence that General Ulysses S. Grant played Nine Man Morris during lulls in the War or otherwise.

Pigs In Clover

Remember, J. Fenton trademarked Three Blind Mice on May 7, 1889. Well, U.S. Patent No. 410,956 was issued on September 10, 1889 to Charles Martin Crandall of Waverly, New York[6]. It covers the invention of the game known as Pigs in Clover.

Unlike “Three Blind Mice,” there is no sheet music, folk song, or published lyrics from the 18th or 19th century which directly match Pigs in Clover in known archives like the Library of Congress or American Revolution song collections.[7]

While marketed as Pigs in Clover, Crandall simply patented a “Game or Puzzle.” The patent describes a circular maze game with concentric tracks and barriers, designed to guide small clay marbles (the “pigs”) into a central enclosure (the “clover”). The player tilts the board to maneuver the balls through the maze — a classic dexterity challenge.

This patent is the legal foundation for the Pigs in Clover craze that swept the U.S. in 1889, inspiring countless imitators. It became a landmark in American toy history.

So What’s the Difference?

From a mechanical standpoint there is no difference! Three Blind Mice had copyright protection for its artistic expression (words, music, illustrations) while Pigs in Clover had patent protection for its mechanical design and game play.

But when Three Blind Mice was adapted into a dexterity game — likely in the 1890s or early 1900s — it was piggybacking on Crandall’s maze format. So yes, the theme came first, but the mechanics were borrowed.

And many more maze-games, most very similar to these two, popped up throughout the last couple of decades of the 19th century. They were very similar, they were played by both children and adults and they became, in contemporary language, a social phenomenon. There was a maze craze!

Patent Allowed

While looking at the old Three Blind Mice box cover, we found another odd legal notation which we had not seen before and which held no meaning at all for us. The phrase is “patent allowed”.

We learned that “Patent Allowed” typically means that the U.S. Patent Office has reviewed the application and agreed that the invention meets the criteria for patentability.

However, it does not mean the patent has been officially granted yet. The applicant still needs to pay the issue fee and complete final steps before the patent is formally issued and assigned a number. Manufacturers often printed “Patent Allowed” on packaging as a marketing signal—to suggest innovation and legal protection were imminent.

It also served as a warning to competitors that a patent was in progress and might soon be enforceable. Remember, Crandall was already patented and, we imagine, on the market by now while Fenton was playing catch up.

We can find no evidence or record of a United States patent specifically granted for the Three Blind Mice toy version. What probably happened is that the patent may have been abandoned before issuance. And another common practice was to get the patent allowed but never finalized. The “Patent Allowed” was a marketing ploy to help sale mice and not pigs!

On Sale In Buffalo!

James Fenton was a game inventor and likely a toy designer with a base of operations in Buffalo, New York. His patent filings and business listings from that era place him in Buffalo. He was affiliated with a small-scale manufacturer and a novelty company distributor in Buffalo, New York.

It’s unclear whether Layton’s maze version was widely manufactured or distributed, but it may have inspired later maze games, including Milton Bradley’s 1925 version of the game by the same name.

The Queen City of the Lakes

Buffalo, New York in the 1880s and 1890s was a booming industrial city, often referred to as the “Queen City of the Lakes.” Its strategic location at the eastern end of Lake Erie and the western terminus of the Erie Canal made it a powerhouse of trade, manufacturing, and innovation.

There were over 255,000 people in Buffalo in 1890—far more than enough to serve as a viable market for any number of dexterity games! In the 1880s–1890s Buffalo was a city on the rise—electrified, industrialized, and culturally ambitious. The City, a transportation hub, adopted hydroelectric power from Niagara Falls.

Charles M. Crandall

Charles Martin Crandall lived in Montrose, Pennsylvania and later operated his toy-making business out of Waverly, New York. His early work began in Covington, Pennsylvania, where he inherited his father’s woodworking factory. Waverly is about 160 miles from Buffalo.

Charles took over his father’s woodworking and furniture factory in Covington, Pennsylvania, at age 16 in 1849[8].

In 1866, Crandall moved the factory to Montrose, where he began producing toys like interlocking building blocks.

“Crandall applied fastening techniques he learned in carpentry to the wooden toys he invented. The tongue-and-groove joint, for example, replaced nails in the first building blocks he made. Other tongue-and-groove toys soon followed. Crandall combined the novelty in woodworking technology with the whimsy of a kid at play, which led to some pretty fanciful toys.[9]”

By 1889, Crandall had relocated his operations to Waverly, where he invented the wildly popular Pigs in Clover maze game.

OK, Some Legal & Background Work Is Done, But Now We Have To Sell It!

Buffalo Evening News, 23 March 1889, np[10]

Fenton Sales Local

This add tells us a great deal about Fenton’s approach to selling his Three Blind Mice. First, notice that he proclaims that his maze game is the latest and that it beats all other maze games on the market—that is Crandall’s Pigs which he also names in his add.

This advertisement quotes the price of the game as 15 cents. This seems expensive to us. On the other hand, Fenton had few options at the time to compare the value to.

That 15¢ in 1889 is worth about $5.34[11] in 2025 dollars. But consider this: 15¢ in 1890 would also buy: a pint of oysters; a pound of coffee; or a ticket to a vaudeville show.

The Buffalo Toy Company

Buffalo Toy Co. appears to have existed in various forms across several decades, though its identity evolved over time. It existed in some form from the 1880s until the 1940s.

It seems “Buffalo Toy Co.” was not a brick and mortar factory. It was not even a standalone company in the strictest sense, but rather a brand identity or trade label used by manufacturers like Buffalo Toy & Tool Works. This was common in the late 19th century practice: firms would market toys under multiple names to appeal to different audiences or retail channels.

So, Crandall’s wood and cardboard maze was probably manufactured by a regional foundry or tool works and then distributed by a merchant like Barnum & Son. It was later absorbed into the Buffalo Toy & Tool Works lineage.

Title: “S.O. Barnum, Son & Co., No. 265 Main Street, the largest variety of goods for the holidays”

There are a couple of other notations of importance in the ad. Evidently The Buffalo Toy Company manufactured Fenton’s game and it was for sale at the department store S.O. Barnum & Son. To have it listed by Barnum[12] was quiet the coup d’état.

Stephen Ostrom Barnum (1815–1899), originally from Utica, NY, founded the firm in 1845 as Barnum Brothers, a wholesale and retail novelty business located at 265 Main Street in Buffalo. By the late 1800s, it was known as S.O. Barnum, Son & Co., and it had become a prominent destination for holiday goods and novelties.

The store was celebrated for offering “the largest variety of goods for the holidays,” suggesting a dazzling array of toys, ornaments, and seasonal merchandise.

The bottom line is this—Fenton went local with his sales. We can’t possibly know, all these years later, whether it was a conscious business decision to go local or if it was apparently the most logical and feasible thing to do at the time.

The Buffalo Evening News, Friday, March 29, 1889, np.

The Buffalo Evening News, Friday, March 29, 1889, np.

Crandall Looks For A National Market

Crandall took a totally different approach than Fenton. While Fenton played low and local, Crandall swung for the bleachers. We have read that Pigs was played in the United States Congress. And we also read a delightful story about Crandall’s game being introduced to Japan by a missionary!

And check this ad from a Buffalo newspaper in March of 1889. S.O. Barnum & Sons carried not only Three Blind Mice but Pigs in Clover at the same time! We’re not surprised. Barnum evidently distributed any toy, maze, game, or novelty that would sell.

Price Differential

Remember, Fenton sold Three Blind Mice in Buffalo for 15¢. Well the original retail price of the Pigs in Clover game, when it was first marketed in 1889 by Charles Crandall and distributed by Selchow & Righter, was 10¢[13]. Based on inflation data from 1889 to 2025, in 2025 dollars the games cost $3.52 as compared to $5.28[14].

In 1889, a dime could buy small luxuries, basic goods, or a bit of entertainment, which was enough to treat yourself or a child. A loaf of bread cost about a nickel to 7¢, a whole pound of apples or potatoes was about 2-5¢, a pint of milk was about 3-5¢, two rides on the streetcar cost a dime, and a shave and a hair cut also cost a dime.

The list goes on and on. The point is simple: the maze games were expensive, regardless of who manufactured and sold them, considering that they were rather crudely made from cardboard and wood. And S.O. Barnum & Sons carried both mazes and evidently in the same bins. How could that work?

Like A Rocket!

However that worked out, Pigs in Clover was a sensation—so popular that it reportedly sold hundreds of thousands of units within weeks and even inspired political cartoons and parodies. Compared to the 15-cent Three Blind Mice game, Pigs in Clover was slightly more affordable, and arguably even viral in its day.

We cannot find the actual Crandall sales figures but consider that if he only ever sold 100,000 Pigs games. That is $10,000 in1889, which is equivalent to about $352,148 in 2025.

Back then, it was a small fortune: enough to buy land, build a house, start a business, or live comfortably for years[15]. In 1889, $10,000 was more than most people earned in a decade. A skilled laborer might earn $500–$800 per year while a schoolteacher earned $300–$600. So this sum could represent a lifetime of savings, an inheritance or the seed of a legacy. And from the evidence that we have seen, Crandall sold “hundreds of thousands of units!”

Selchow & Righter[16]

Selchow & Righter was founded in 1867 and was based in Bay Shore, New York. The Company helped define American leisure culture — from Victorian parlor games to post World War 2 family game nights. Their success with Scrabble and Parcheesi, like this story about marbles as cultural motivators, reflects a shift from handcrafted play to mass-market entertainment.

We are unsure how Crandall chose Selchow & Righter, but their business model in 1889 was considered a jobber. It primarily produced and licensed games developed by others like Crandall. It focused on domestic manufacturing and wholesale distribution. Crandall’s customer pool was effectively nationwide as compared to Fenton’s.

The New Fad

Crandall’s Pigs in Clover’s

“…success created many imitators, with many of them succeeding in cashing in on the toys popularity. Industrialist Moses Lyman, a financial backer of Crandall’s business ventures, actively pursued them all by bringing them to court for patent and trademark infringement.

A major obstacle in this pursuit was the slowness of the patent office approval and Crandall’s own delay in filing the patent (the patent was filed in February 1889 one month after the toy’s release). Despite the many imitators, however, there seemed to be little affect on the output of the “Pigs” game. More than one million of the games were sold by late April 1889 as reported by Lyman. The patent was finally awarded in September of that same year, about the time the toys popularity began to decline.[17]” Emphasis added

Evening Journal. (Wilmington, DE) 30 Mar. 1889, p. 2. Retrieved from the Library of Congress,

www.loc.gov/item/sn85042354/1889-03-30/ed-1/.

Charles Crandall moved his operations to Elkland, Pennsylvania in the 1880s. His company, often referred to as Crandall’s Toy Works, specialized in wooden toys, building blocks, and puzzles.

So, it was Crandall who heard of Lynam’s toy and who gained “exclusive rights” to the toy.

From our viewpoint, Fenton, Lynam, and other imitators simply spread the use of the hand-held maze among both adults (who were fascinated with game) and children.

From Marbles To Memory

What began as a marble maze in the 1880s became more than a pastime. It reshaped how people thought about play, challenge, and culture.

The marbles still roll, carrying history with them.

Lone players with four clay marbles built dexterity skills and persistence. What began as the quiet tilt of a marble maze soon echoed in the clatter of bagatella games and the ring of marbles striking earth. Each game carried forward the skill of the last, reshaping play into new forms.

By the late 1880s, these transitions were more than a pastime—they were cultural rehearsals of dexterity, patience, and chance. Marble fads came and went. The marbles rolled from table to ground, from solitary puzzle to communal contest, leaving behind not just games, but a legacy of how play itself evolves.

The tilt of the maze, the flick of bagatella, the aim of the ringer — each skill folded into the next. And when glass marbles flooded the market at century’s end, they ensured those skills were practiced everywhere. The story of play was no longer about scarcity, but abundance. The marbles kept rolling, reshaping culture as they went.

References

- See https://www.onesourceauctions.com/ (9/30/2025) One Source Auctions is based in Canandaigua, New York, and operates under the name One Source Estate Services. ↑

- See our story “Bagatelle Blues” @ https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/bagatelle/ 9/30/2025 ↑

- You can read all about the nursery rhyme, which we still do not fully understand @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Blind_Mice 10/3/2025 ↑

- Verbal permission to use the images of the game given by Mr. Rox on September 29, 2025. ↑

- Bilbo Catcher | Historic Jamestowne, Cup-and-ball – Wikipedia, Colonial Games and Music Trunk Contents, Bilbo Catcher, & Childrens Toys and Parlor Games of the 19th Century (1800s) all 10/21/2025 ↑

- US410956A – crandall – Google Patents ↑

- You might want to see “Pigs in Clover” @ Pigs in clover – digital file from intermediary roll film | Library of Congress 10/24/2025 ↑

- See Christina Rubin’s “Crandall’s Pigs in Clover”, The Antique Toy Collectors of America, Inc. @ https://atca-club.org/crandalls-pigs-in-clover/ 11/2/2025 ↑

- Patricia Hogan, “Charles M. Crandall Toys—Vintage Playthings, Modern Play.” The Strong Natural Museum of Play @ Charles M. Crandall Toys-Vintage Playthings, Modern Play.

- https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=ben18890323-01.1.10&srpos=3&e=——188-en-20-ben-1–txt-txIN-Three+Blind+Mice——— 10/28/2025 ↑

- Based on a cumulative inflation rate of approximately 3.460%, meaning prices today are roughly 35.6 times higher than they were in 1890. $15 in 1890 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator 11/2/2025 ↑

- S.O.Barnum, Son & Co., No. 265 Main Street, the largest variety of goods for the holidays.[Between 1860 & 1890] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2017660512/ 11/2/2025 ↑

- The Strong National Museum of Play. https://www.museumofplay.org/ ↑

- These conversions use a multiplier of 35.21×, reflecting the cumulative inflation rate over 136 years U.S. Inflation Calculator. ↑

- $10,000 in 1889 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator ↑

- If you’re interested in this game company then you might want to see “Selchow and Righter Explained” 11/10/2025

- “Crandall’s Pigs In Clover” The Antique Toy Collectors of America, Inc. @ Crandall’s Pigs in Clover – Antique Toy Collectors of America 11/8/2025 ↑