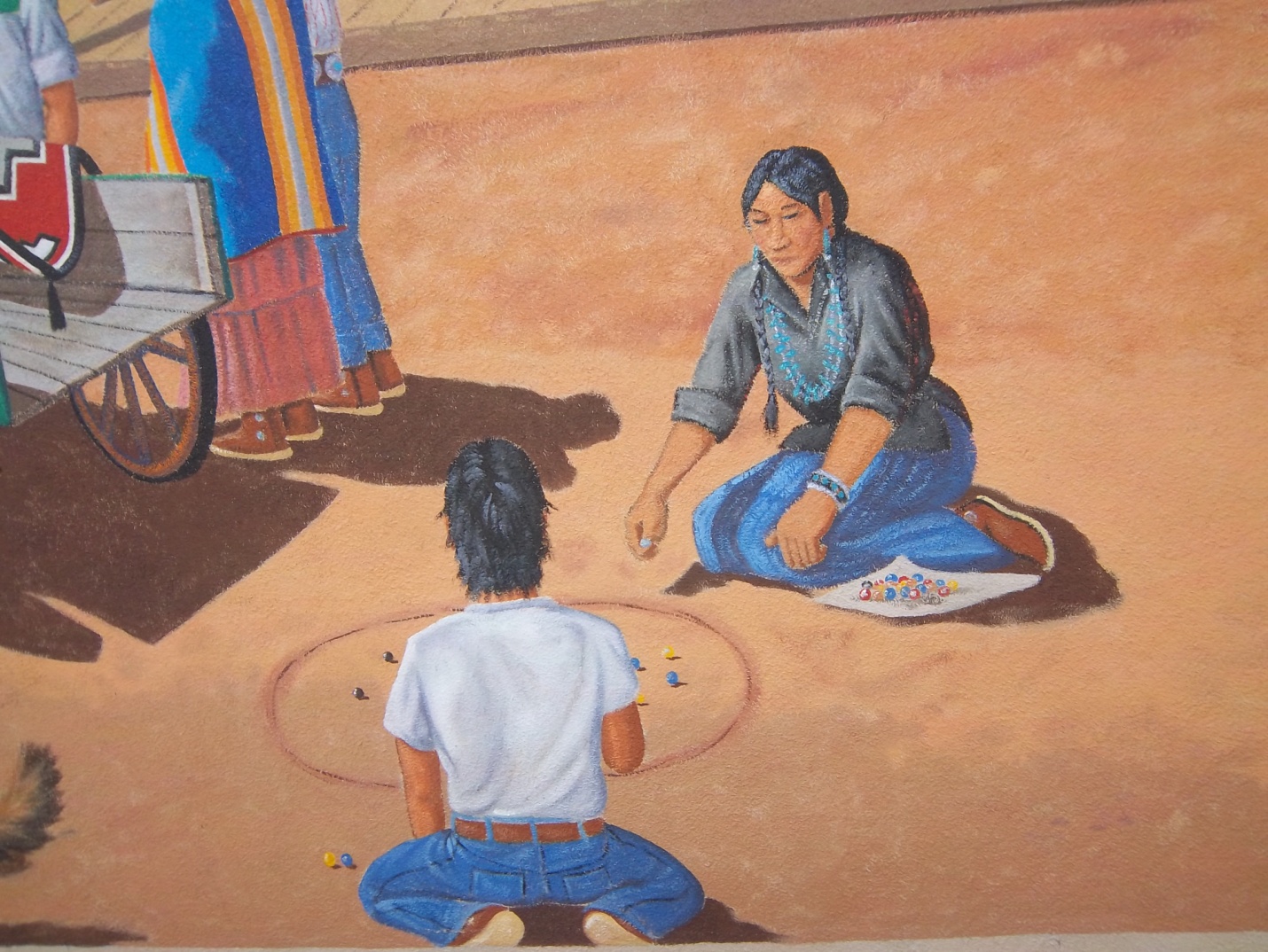

Portion of a Mural, Downtown Wetumpka, Alabama

“Native American” or “First American” is too broad a term for meaningful discussion about marbles, gaming, warfare, family and culture and social institutions. There are two approaches to organizing our thoughts: timelines and cultures. You might find that “Beneath the tides of sleep and time strange fish are moving.” Thomas Wolfe From Death to Morning

Cultural Approach

For example, are we writing about the Cherokee peoples, the Akimel O’odham, or the Odawa? The Federal government recognizes 574 “…Indian Nations (variously called tribes, nations, bands, pueblos, communities and native villages) in the United States. Approximately 229 of these ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse nations are located in Alaska; the other federally recognized tribes are located in 35 other states.”

Additionally, some state governments recognize tribes. For example, North Carolina recognizes eight different tribes.[1]

A Matter of Time

In prehistory no written records existed. Native Americans have a very long and very rich prehistory.

Native American culture can be divided into distinct time periods. Keep in mind that these periods are neither fixed nor absolute. They are mental constructs which are being explored and revised as new evidence is discovered.

Generally agreed upon time periods: Paleo Indian (Lithic stage)– 16,000 BC to 8000 BC; Archaic Period – 8000 BC to 3000 BC; Woodland Period – 3,000 BC to 1000 AD; Mississippian 1000 to 1520 AD; and the Historic Period – 1520 AD to present.

In this post we are considering the two cultural periods of the Mississippian and the historic: about 1000 – present.[2]

Holding On to The Past

We first learned about Stewart Culin online at the Penn Museum Archives, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He was born in Philadelphia in 1858. Considering all the books that he wrote, the professional museum exhibits that he built all across America and abroad, and the places where he taught, we find it almost unbelievable that he was a self-taught scholar who did not have professional training.

One of the things that we most value about his work on Native American games is that he traveled all over the United States collecting material for the Brooklyn museum.[3]

He continued his trips to the American West until 1911, collecting Native American material for the Museum of Brooklyn. He accumulated an extensive collection of material from native cultures in the American West.

His Book

Games of the North American Indian was first published in 1907. At that time it was published as the twenty-fourth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology.[4].

Incredibly the 1907 report runs to 864 pages! Since 1907 the report has been published in book form and it has also been published in two volumes. Culin’s book is the most complete work ever prepared on the subject of games.

His information is based on museum collections, travel and first-hand ethnographic accounts, and his own research. The report covers over 200 tribes and everything from games of chance and dexterity to such minor amusements as shuttlecock and tipcat. Finally, Amazon concludes, there are 1,112 figures!

And, as noted above, there are versions of the book online including a searchable version.[5]

What Are Native American Marbles Like?

The Cobble Marble

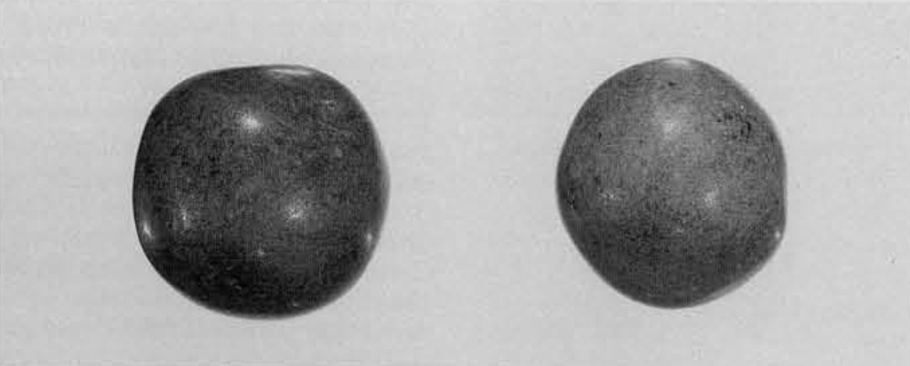

The marble to the right in the photograph above is a natural cobblestone. We bought it in December 2008 at an Antique Mall in Holly Hill, Florida. It has taken us years of study to understand just what it is and how it fit into the Native American culture of the Mississippian peoples (about 1000 current era – European contact).

First, it isn’t round but is slightly ovoid. We have learned that there is a reason for that. It is about 1¼” in diameter and it weighs 30 grams. It is a cobble of white granite with dark, almost blue, inclusions with a few reddish inclusions. A cobble is larger than a pebble but smaller than a boulder.

Considering what we have learned over the last fifteen years we believe that this cobble was made by First Americans living in the Southeastern United States during the Mississippian Period. While there may have been as many as 170 tribes and bands of people in the Southeast then, we are convinced that someone in one of these tribes made and used the marble: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. More specifically we believe that it is Cherokee and possibly the Creek.

Did the Cherokee and Creek have access to natural granite cobbles? Yes, in the Southeast granite like this marble is fashioned from is found in Georgia, Tennessee (the Great Smoky Mountains are made-up of granite), South and North Carolina, and Maryland.[7] And both the Creek and Cherokee had extensive trade networks in the Mississippian Period.

Is This Ovoid Marble Natural or Man-made?

It is both. When Native Americans used lithics to fashion tools, weapons, or, in this case toys, we say that the stone is cultured or worked. And how it is cultured is fascinating. For many years we had heard that Native Americans cultured natural cobbles which they had found, mainly in stream beds and dry washes, into marbles.

The Cherokee or Creek may have chipped the stone before rounding, but the real magic was the waterfall! In September 2016 at the 34th Anniversary National Rolley Hole Championship in Standing Stone State Park, Hilham, Tennessee we bought the book A Stone’s Throw by Darren Shell.

Shell has a photograph of a Tennessee Marble Mill on page 11. Historically, rolley marbles are made of flint and today they are made by machine.

This photograph above shows a modern machine finished rolley marble in play by the gentleman at the tournament. It is made of Cumberland flint and is about ⅞”. Compare this flint marble with the white granite Cherokee or Creek marble!

Making Prehistoric Marbles

The Cherokee, Creek, and other tribes as well as the early settlers in the Cumberland made marbles from whichever cobbles were available. Shell confirms the essentials of prehistoric marble making. Round or semi-round stones were collected. They may or may not have been worked to achieve a more round shape. In our case the marble was ovoid both when found and when finished.

The cobbles were taken to a small waterfall, which are abundant throughout the Southeast. At the waterfall the First Americans looked for or fashioned a hole in the underlying rock.

A cobble was placed in the hole and left to tumble for weeks or even months. It was checked from time to time, and when it was considered finished, like our marble, it was taken out of the rolley hole and play began! As you can see, this marble is not planar; any surfaces left from fashioning the marble were removed by the swiftly moving water.

What’s That Other Thing? The One on the Left?

We are certainly not finished talking about Cherokee marbles. But first, we want to discuss the marble to the left in the photograph above.

We bought this marble in 2011 at the “Tuesday Market” in Summerville, Georgia.

It is a Native American marble almost certainly made of granite. It weighs 50g and is just <1⅜”. The stone is covered with pressure knapping marks and has one planar surface. Knapping of this kind was usually accomplished with a deer tine (antler). The marble also has traces of red ochre. It is possible that at one time the marble was “painted” red with ochre.

Summerville, Georgia, is in Chattoga County just north of Rome, Georgia, which is in Floyd County. Summerville is some 25 miles east of the Alabama line; across the line is Cherokee County, and, north of the Little River, De Kalb County, Alabama. In prehistoric times all of this territory and much more was controlled by the Creek Nation. Based on history, we think that this marble may well be historic rather than prehistoric and we propose that it dates to ca. the 1700s.

A Treasure in the Rough

The next ball we are discussing is in the photo above. It is to the far right back row. We bought this game ball (or marble) in June 2018 at the Etowah Valley Artifact Show, Cartersville, Georgia. Where we bought it is an important Cherokee historic site. It was “home to several thousand Native Americans from 1000 A.D. to 1550 A.D. This 54-acre site protects six earthen mounds, a plaza, village site, borrow pits and defensive ditch. Etowah Mounds is the most intact Mississippian Culture site in the Southeast.”[8]

We bought this game ball from the same collector who had the claystone ball, which is in the back row in this photograph and third from the right.

We did not buy this one until we checked the entire show. No one else had marbles or game balls for sale although we were amazed at the total number and wide variety of marbles and game balls which individuals have found, bought, or traded over the years.

Collectors who do sell some of their own artifacts are tightly guarded about the items they sell and they keep them in private collections under glass.

This ball is 1⅞” and it weighs a hefty 170g. It, too, is made of granite with shiny red feldspar. The surface is planar to the point of being almost square, and the surface is pecked all over with some type sharp tool and a hammer stone. The way this one is worked is unlike what is accomplished with a deer tine.

Stick Ball Core

The owner had no more balls or marbles and no meaningful provenance/provenience which he would share with us. He did tell us that the smooth, almost slick, clay ball was fashioned to fit inside a natural hide cover which was then used to play stick ball. We agree with this assessment, and we also know that stick ball often resulted in broken bones or even worse.

He implied that the stick ball core may have been found in Ohio. So, it is impossible to say whether it belonged to the Miami, Delaware, Wyandot, Ottawa, or one of several other tribes or bands.

We won’t pursue the history of stick ball any further but will focus on the artifacts which we either know are or we believe to be marbles.[9]

A Pecky Granite Marble?

At the time we bought it we questioned whether or not this granite ball, too, fit inside a leather cover to provide weight in a stick ball game. This little ball must have been remarkably difficult to work into a sphere. It is as hard as a steel knife.

However, we never believed it to be a stick ball core. Certainly, the planar surfaces would not matter inside a leather cover. But it just seems all wrong based on all the game cores which we have seen and collected.

Culin to the Rescue

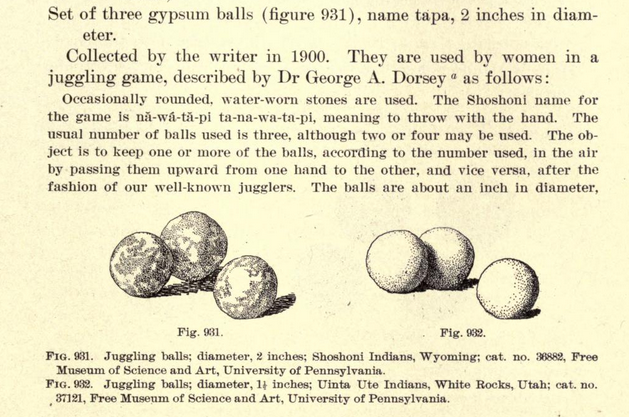

Screenshot from Culin Games of the North American Indian page 713[10]

Compare Culin’s pecky marble in Figure 931 (to the left on the page shot above) to our granite marble to the far right. The marbles in Figure 931 are 2” in diameter and ours is 1⅞”.

They are almost identical! Culin writes that “two perforated marbles collected by the writer in 1900. They are called marapai and are said to be used in juggling. …The Shoshoni name for the game is nawatapi meaning to throw with the hand.” The prehistoric Shoshone people lived Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Nevada.

Hand Games

No, we do not believe that our marble is Shoshone. We believe that it was made east of the Rockies. On the other hand, it was almost certainly a marble used in hand games.

This would explain the weigh, size, the pecks made in the marble with a hammer stone, and the odd planar surfaces. Both the “perforations” and planar surfaces made it easier to catch and to hold onto in hand games.

It was made to juggle or otherwise to be used in some other type hand game. And it was perfect for most of them.

Hand games were games of chance played in some form throughout both the prehistoric and post-contact periods. Culin tells us that hand games were found among 81 tribes belonging to 28 different linguistic groups!

Cherokee Marbles

We have talked about how the Cherokee, Creek, and doubtless other Southeastern tribes made marbles using natural cobbles and waterfalls. We have also explored how they played rolley. For comparison with more contemporary games, view an earlier post What A Spectacle! National Championship and Tournament Marble Medals

But many questions remain. Fundamentally, did the Cherokee play marbles before white contact? To say the least there is disagreement on this point.

I wrote to archivists at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, North Carolina.[11]We visit the Museum each time we stay in Cherokee and we highly recommend it.

Lead Cultural Specialists sent us this email from the Museum: “I currently do not have any resources on hand but as far as I know we have played marbles long before the European Invaders came to this land.” We know that this sentiment is still echoed in all three Cherokee Nations today.

Cherokee Rolley

Darren Shell in A Stone’s Throw (pages 36 -37) suggests that cobblestones like this, which were worked and water-tumbled, were used in prehistoric Rolley-hole. He also believes that the Cherokee introduced the marbles, how to make them, and how to play rolley, to the frontier families settling in the Upper Cumberland of Tennessee and Kentucky rather than the whites teaching the Native Americans!

We bought this marble in Walland, Tennessee, in the Smoky Mountains, in May 2023. It was sold as a Native American marble. Like our white granite, it is ovoid, 1⅜” around and about 2” long. It is also heavy at 60g. It is dark in color and the marble is made of quartzite. It was probably found nearby in East Tennessee.

Our marble has a few pecks, either from play or storage by the Cherokee, as you can see in the photo above.

Otherwise, it is almost identical to Figure 7 (above: Two marbles; Penn Museum Object Number(s): 46-6-151) in Bonita Freeman-Whitthoft’s paper “Formal Games in the Cherokee Ritual Cycle” (Expedition Vol. 30.2, pages 53-60).[12] Freeman-Whitthoft writes that marbles is a borrowed game in Cherokee culture.

The Cherokee Peachtree Site in North Carolina

AThe notation with the object in the Penn Museum reads: “Fig. 7. Cherokee marbles of quartzite purchased by John Witthoft in 1944 from a collection in Rockhill, South Carolina, labeled as having been found on the Cherokee site of Peachtree.”

The formal study of the Peachtree site by Setzler and Jennings was published in 1941[13] only three years before Witthoft bought those marbles in South Carolina.

Peachtree is a lesser-known burial and ceremonial site and we understand that it is now on private property. The Blue Ridge Highlander tells us that Peachtree is Archaic (8000 – 1000 BC); it is a burial site with 68 graves; and some 250,000 pieces of pottery have been found there.

Treasure Hunters Found Peachtree

The site was scavenged in 1885 and dug by the Smithsonian Institution in 1933. It is reported that some evidence from the site remains inconclusive because of the treasure hunters.

The 1941 Setzler and Jennings report notes (p. 56) “that evidence of games is restricted to the hundreds of discoidals found. That the smaller ones figure as counters in hand games, gambling, or similar amusements is probable.” Counters ranged as small as ¾”.

Discoidals & Counters

We have bought a number of these discoidals over the years. They are as inexpensive as stone marbles and considerably less rare. They are also called chunkey stones. They are game pieces traditionally used in skill games and gambling. These are not marbles.

While Setzler and Jennings do not mention prehistoric marbles, they do discuss “counters” used in hand games. Remember, this is the Archaic Period centuries earlier than the Woodland. We would expect the Native Americans to have far fewer game pieces of any kind than in the Mississippian Period.

We are confident that Setzler and Jennings’ hand game counters are in fact prehistoric marbles like the ones we have been discussing. We have no reason not to accept Freeman-Whitthoft’s word about the counters (marbles) being dug at Peachtree.

The key idea is this: Peachtree pushes back the timeline for Cherokee marbles by centuries and it underscores the fact the they played marbles long before the “Invaders” arrived!

The Cherokee and the 7 Sisters

While Peachtree underscores that Cherokee marble games are ancient and that they date to prehistory, there is much more evidence to be found in the tribes’ cosmology, culture, and life ways. Freeman-Witthof, whom we introduced above, writes: “It has frequently been suggested that all games originated as ritual, and were then secularized into gambling and amusements. The Cherokee provide an unusual case, where the original nature of the games is still very apparent, and the transformation from religion to sport can be traced and understood.”

The Cherokee account about the origins of the Pleiades constellation, as one example, is one of many different First American’s cosmological myths. All of the accounts explore the missing seventh star and they account for it in different ways.

The Pleiades are also known as the Seven Sisters. The Cherokee, and other tribes’ story, concerns the idea that one of the seven stars has faded leaving only six stars visible to the naked eye. In fact, depending on how dark the night sky is and just how well the observer can see, may mean that there are more or less stars in the Pleiades.[14]

Frankly, we prefer the Cherokee account as told by Freeman-Witthof: “Once there were seven boys, close friends, who became so engrossed in the marble game that they lost track of everything else. They played day after day, neglecting to go home, eat their meals, or take care of anything else. As they wasted away, they became light and buoyant. Their mothers became very worried about them and came to take them away from their obsessive game by force. As their mothers tried to seize them, they floated up in the air and six of them escaped, but the seventh mother caught her boy by the feet and pulled on him. In their struggle, she pulled him down to the ground, but he penetrated into the soil and became a yellow pine tree, the first of its species. The others went off into the sky. In the winter they return to earth to visit their lost friend, but in the spring they rise above the horizon and again escape the earth.”

It is because of this account that the Cherokee are confident that marbles is a prehistoric game in the tribes. After all, ceremonial marble games are played during the time that Pleiades rises in the spring sky.

Look Both Ways

While marbles, or rolley is an ancient Native American game, it is still much more popular in the Cherokee culture than it is among the Anglo-Americans of the Cumberland. Just Google “Cherokee Marbles” if you doubt us.

Traditionally Cherokee marbles uses a five hole game although there is a four hole variety. While prehistoric Cherokee played with stones like the ones in our collection, today they generally use billiard balls. The game can be played in teams or alone.

A National Tournament is held annually during the Cherokee National Holiday, and marbles is a part of the curricula of students who attend Cherokee Nation schools.[15] The future of Cherokee marbles is bright.

Solving the Mystery  .

.

We want to give you some idea of how to learn more about any Native American marbles and artifacts which you may find. We will use our little mystery artifact to give you some identification tips.

We bought it from a gypsy seller in Central Florida in 2019 who knew absolutely nothing about it.

It has a 21/64” hole on one pole and two holes on each body wall. It is made of grit-tempered pottery. Since we bought the artifact in Florida, we wrote an email to Susanne Hunt, Outreach Programs Supervisor at the Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources about the little artifact. She and her staff we unable to help us with what is an oddity.

Next we took the odd little artifact, which some who have examined it have claimed to see an effigy on one side, to the Etowah artifacts show (mentioned above) to see if any collector could identify it.

By this time we had taken it to the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, North Carolina. Indigenous staff at the Museum, as well as one other Cherokee, identified it as a pendant. We had been told earlier that it is some type gorget.

One individual at the Etowah Show described it as a pendant. The collector further explained that the pendant was made to hold rattles. We learned earlier that rattles of all kinds were extremely important to Native American tribes in the Southeast. Finally, he noted that the rattle is made of grit with a heavy concentration of iron in the matrix which pins the pendant to the Tallahassee area of Florida.

So, identifying unknown indigenous artifacts is hardly different from working with glass marbles. Most are straight forward; some are very difficult, but fun, to identify!

Bring It On

Why not add a few Native American marbles and game balls to your collection. They are not rare and, as a rule, they are inexpensive. Often $5.00 will go a long way!

Check out any artifact shows near you. Flea markets, antique stores, and antique fairs are good places to look. You may find chunky stones, marbles, and game ball cores which fit inside stick balls covered in leather. You probably won’t get much of a back story with the artifacts. Still, listen for keywords which can help you learn more about it online. Why not add a new and often mysterious element to your marble collection?

Portion of a Mural Grand Junction, Colorado

Portion of a Mural Grand Junction, Colorado

Footnotes

- https://www.ncai.org/about-tribes (5/29/2023); https://americanindiancenter.unc.edu/resources/faqs-about-american-indians/ 5/30/2023 ↑

- Adapted from & slightly modified from https://www.legendsofamerica.com/native-american-archaeological-periods/ (5/30/2023) Note archaeologists generally use the term “lithic” rather than stone. In terms of time and cultural periods lithic means the period when the First Americans started and used stone tools which they created or modified from cobbles or other stone. ↑

- https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/research/culin/ 6/2/2023 ↑

- Culin, Stewart. 1907. “Games of the North American Indians.” in Twenty-fourth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1902-1903, 3–809. Bureau of American Ethnology ↑

- https://archive.org/details/gamesofnorthamer00culirich/mode/2up?q=marbles 5/31/2023 ↑

- rock. https://geology.com/rocks/granite.shtml (6/4/2023) According to an online dictionary an amphiboles is any of a class of rock-forming silicate or aluminosilicate minerals typically occurring as fibrous or columnar crystals. ↑

- If you are especially interested in geology then you may want to view or download this PDF: Watson, Thomas Leonard. Granites of the Southeastern Atlantic States. Department of the Interior. United States Geologic Survey. Bulletin 426. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1910. ↑

- https://gastateparks.org/EtowahIndianMounds (6/5/2023) You may also want to check out the Etowah Valley Historical Society @ https://evhsonline.org/archives/52123 6/5/2023 ↑

- If you want to know more you can check out “Stickball” on the Chickasaw Nation @ https://www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Culture/Society/Stickball.aspx (6/5/2023) and “Stickball” on the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma @ https://www.choctawnation.com/about/culture/traditions/stickball/ 6/5/2023 ↑

- https://archive.org/details/gamesofnorthamer00culirich/mode/2up?q=marbles 5/31/2023 ↑

- https://cherokeemuseum.pastperfectonline.com/ (6/5/2023) We have the names of the Specialists who wrote us in our files, but there is no reason to list them here. ↑

- The paper is in PDF format @ https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/formal-games-in-the-cherokee-ritual-cycle/ 6/5/2023 Photograph of Figure 7, 46-6-151 courtesy of the Penn Museum. ↑

- Setzler, Frank M. and Jennings, Jesse D. 1941. “Peachtree Mound and village site, Cherokee County, North Carolina.” Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. 131:1–103. PDF format @ https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435030403950&view=1up&seq=57&q1=games (6/5/2023). . You might also want to browse the gorgeous photographs of Cherokee County, NC, where the Peachtree Site is located, at https://theblueridgehighlander.com/cherokee-county-peachtree-north-carolina.php 6/6/2023 ↑

- https://science.nasa.gov/pleiades-seven-sisters-star-cluster 5/31/2023 ↑

- Adapted from https://dbpedia.org/page/Cherokee_marbles 6/6/2023↑