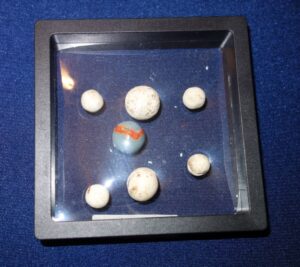

A few weeks ago we received an email from a gentleman [1] who we will call Jeff in this story. He lives in St. Louis, Missouri. Here’s what he said: “Larry, please look at the pictures of these ‘marbles’ and see if they are something you are interested in.”

“By the way, I am not one of your readers. I am not a marble fan. I found you on the internet because I googled[2] ‘Indian marbles’. You came up at the top. I didn’t know what I found in the dirt but that is the first thing that came to mind – that they were marbles.

I actually found one of the blue/orange ones first. I wondered why anyone would make oblong marbles. Days later I found another one and the other stone ones. I hope they are what you are looking for. I’m quite sure that there are others but I was not on a quest to find marbles but to dig holes for concrete piers. Since I live close to a creek (just out of the flood zone) I suppose the Indians settled here too back when. Who knows. I found these about a foot down or so when the dirt changed abruptly to clay.”

Jeff told us that he did not want money for the marbles but was just looking for identification help. We believed that he wanted to know two basic things: are the marbles stone and were they crafted and used by the Native Americans who lived in the area?

Photo by Jo Garrett

Let’s Get Started

He sent us these marbles to examine. We carefully examined the glass marble with a blue base and faded red ribbon first with the goal to eliminate it because it was not the focus of the gentleman’s inquiry. You can see that this blue-based marble is badly damaged in the lead photograph to this story. It looks to us like it was damaged in a post-production fire, but, if not, then it is a factory cull which probably happened during the cooling process at the plant. In this latter case, it was probably discarded at the glasshouse.

Although it can be very hard to identify any individual dug marble we do believe that the glass one is Alox. The Alox Manufacturing Company (1919 – 1989) was located at 6403–6407 Maple Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri. The factory was less than twelve miles from where the marble was dug.

Alox: The Early Years

Alox Manufacturing Company has an interesting and fascinating history. Some have even said that its marble distribution and later production was “quirky”. John Frier (1895-1974) launched the Company in 1919.

A streetscape along Maple Avenue, St. Louis ca. late 1920s – early 1930s as imagined by Microsoft Copilot AI

What’s In A Brand Name?

Marble Connection writes that the name “Alox” was chosen by Frier for a clever and practical reason: he wanted the company to appear near the front of the alphabetical listings in phone books. That’s it—no mysterious acronym or hidden meaning, just a strategic branding move from the early 20th century. While it sounds apocryphal, we know that our source is trustworthy[3]

We have always been interested in how marbles get their brand name—such as Akro, Jabo, and Das. The name Alox has always fascinated us. However, there is a fly in the “near the top of the list” ointment about Alox.

As imagined by Microsoft Copilot AI

“Who You Gonna Call?”[4]

In reality, the official 1919 telephone books for St. Louis and in most other major cities were arranged in numerical order to reflect the way telephone systems operated before widespread adoption of alphabetical listings. We checked a number of St. Louis Bell Telephone listings in 1919 (when Alox was founded) and well into the 1920s. Residences and businesses are listed numerically[5].

Remember, early telephone systems used central and sometimes regional or neighborhood switchboards operated by humans. Numbers were assigned sequentially, and operators connected calls based on those numbers—not names. A numerical listing made it easier for switchboard operators to locate and connect calls quickly, especially when subscribers were identified by number rather than name.

At least in the earliest days, the number of telephone users was small enough that a numerical list was manageable and logical. In earlier systems you simply asked the operator for a business by name and she connected you.

A Big Change

However, there must have been some advantage to the name in the many directories, gazetteers, rosters, and guides in use at the time.

Saint Louis directories (not the telephone directory) began consistently using alphabetical listings by surname in 1872, when David Gould launched his influential Gould’s St. Louis Directory series. This series marked a shift from earlier formats that were often numerical, occupational, or grouped by neighborhood or exchange.

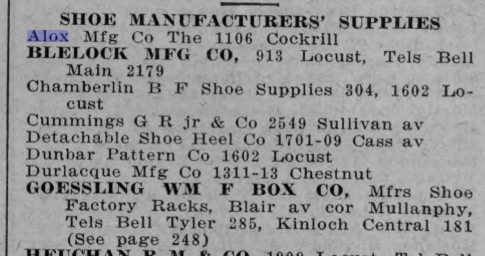

This tiny listing for Alox is number one in the list of “Shoe Manufacturers’ Supplies”. It was published in 1925 on page 363 of the Gould’s Directory[6]! Notice that in this listing Alox is on Cockrill Avenue in the Fruit Hill Neighborhood. Cockrill is only about a mile from Maple Avenue[7].

In the mid-1920s Frier was pitching his product—improved shoe laces and lacing for corsets—to other manufacturers and not to the public!

This page from the St. Louis Business Directory was published the next year (1926). Notice that the Company listed directly under Alox included the Bell Telephone Main number—2179. We wonder why Frier at Alox didn’t do the same thing? For more information about non-marble enterprises at Alox, see the section “The Rest of the Story” at the very end of this post.

Photo by Jo Garrett

Back to Marbles

Well, you know now, if you didn’t before, that Alox Manufacturing Company made shoelaces. They also made marbles. And we know that John Frier was a savvy entrepreneur as well as an inventor. Frier apparently liked toys and he ventured into board games which used marbles. He was also the Kite King. “By the late 1930s he was making all kinds of things for kids: jacks sets, toy whips with whistles on the ends, ‘carnival canes,[12]’ jump ropes, and marble-based board games including several variations on Chinese checkers and Tit-Tat-Toe.[13]”

As fascinating as Alox and Frier are, we turn now to the other marbles in the small St. Louis lot.

Dirt Is Just Clay Without Ambition—& Rain

Clay marbles were popular in the late 1800s to early 1900s, and they were often handmade or molded from local clay. They were inexpensive and widely used before glass marbles took over both popular demand and the market.

Store keepers sold clay marbles made in Germany, and in the first quarter of the 20th century children could buy inexpensive American clay marbles by the paper bag. Each bag cost five to ten cents and each contained about 20 to 50 marbles. Kids could buy the marbles in drug stores, general stores, five-and-dimes, or even as prizes in cereal boxes and penny arcades.

We have found clay marbles in the ruins of drug stores, at old abandoned warehouses, along railroad tracks, near old movie theaters and retail shops. At a long abandoned drug store in Hattiesburg we believe adults used clay marbles to gamble. Not inside the store—out under an ancient pecan tree.

By 1919, about the time Alox began manufacturing shoelaces, clay marbles were already in decline. They were being replaced by machine-made glass marbles from Germany and American companies like Akro Agate and Christensen.

Pills & Pee Dukies

In the late 1880s, Akron, Ohio, became the epicenter of mass-produced clay marbles thanks to Samuel C. Dyke, who invented a device to roll clay into uniform spheres. Check our stories “A.L. Dyke: Man of Mystery” (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/a-l-dyke-man-of-mystery/), and “’River Balls’” & Their Toy Marble Legacy (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/river-balls-their-toy-marble-legacy/).

Kids nicknamed Dyke’s marbles “pills” because they were small, like the four dug in St. Louis and shown on each side of the display box. Due to Dyke’s innovations up to 1,000 clay marbles could be made an hour and one million could be ground out in one day!

Larry’s Father called these little sub-pee-wee marbles “pee dukies.” Although the term pee dukies isn’t widely documented in formal marble literature, it does appear to be a regional or colloquial nickname for small clay marbles, especially those in the peewee size range (typically under 1/2 inch in diameter). Pee dukies may have been a playful or localized term used by children, possibly in the Midwest or Appalachia, to describe tiny clay marbles.

We have no idea exactly how these little clay marbles were played. We have see in the literature that they were small simply to fit better in small hands. And we have also read that they were used as “annies” or targets for larger shooter marbles.

From Clay Pits To Playthings

So, St. Louis had both clay and glass marbles in abundance in the early 20th century. We have established that glass marbles were made in the City, along with other children toys, by the 1930s. But questions remain: Does or did St. Louis City or St. Louis County have clay plastic enough to mold clay or ceramic products such as marbles? Was clay ever mined, processed, and shipped in either the City or in the County[14]? Is there evidence that shows that either entity made clay marbles? For the rest of the story about the links between St. Louis and clay, see the final section of this post

As we explore these questions and others keep in mind what Eugène Ionesco once said: “It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.”

Getting Our Bearings

Remember what Jeff (who accidentally found these marbles while digging holes for concrete piers on his property) wrote in his email: “Since I live close to a creek (just out of the flood zone) I suppose the Indians settled here too back when. Who knows. I found these about a foot down or so when the dirt changed abruptly to clay.”

The gentleman lives in Kirkwood, St. Louis County, about 14 miles from downtown St. Louis. The nearby creek he names is Gravois Creek, which has layers of historical significance. In the 1700s the area around Gravois Creek was home to the Kaskaskia and Tamaron Native American tribes who lived along its banks and utilized its resources. A French Trading post was established nearby, reflecting the region’s role in early colonial trade networks.

In the late 1800s, Italian immigrants mined clay near the creek, supplying material for the Continental Brick Company.

Jeff told us that the clay he struck was not white or buff like the color of the marbles which he dug and sent to us. However, there are indeed sources of white or buff clays in and around the St. Louis area that could potentially be suitable for traditional ceramic or earthenware marble production.

We believe that the clay for his marbles may have been dug somewhere along Gravois Creek and then made locally into “pill” marbles. The broader region surrounding it—especially areas like Dogtown, The Hill, and Tower Grove South—was historically rich in fireclay and refractory clay, ideal for brick making, sewer pipes, and even ceramic wares.

Gravois Creek flows through Webster Groves, Shrewsbury, and parts of Affton, eventually feeding into the River des Peres. It’s a modest but historically significant waterway, especially when you consider its proximity to early clay industries and rail lines.

Kirkwood & Its Role In Clay Transport

Kirkwood was founded in 1853 as the first planned suburb along the Pacific Railroad and west of the Mississippi River. While Kirkwood wasn’t a clay mining hub, it had a strategic location on the Pacific Railroad. The rail line made it a vital link in the movement of clay products.

The Pacific Railroad connected Kirkwood directly to St. Louis and other industrial centers. Clay mined in Cheltenham and surrounding areas was often shipped via rail to factories or distribution points. Kirkwood’s rail station likely served as a transfer or relay point for these goods.

The Pacific Railroad was later known as the Missouri Pacific Railroad and it was pivotal in shaping Kirkwood’s early years. The Railroad was charted in 1849, and, yes, it did connect Kirkwood to the Pacific Ocean[15].

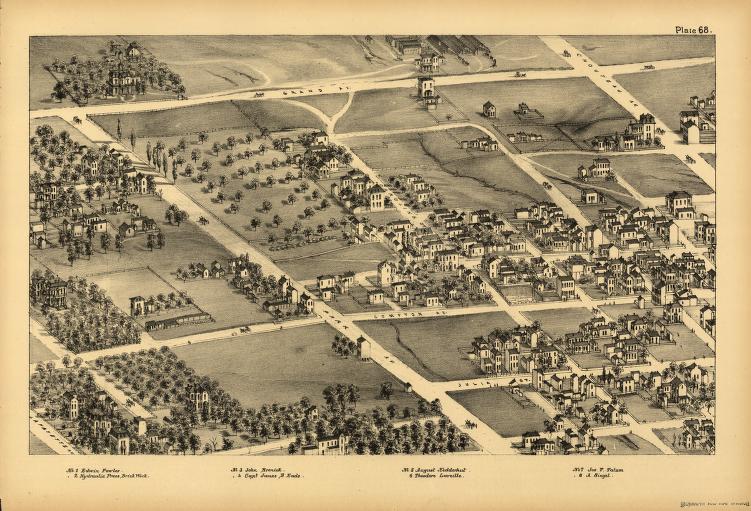

On this 1920 – 1929 screenshot from the larger “Map of Kirkwood Missouri[16]” you can see the east –west Missouri Pacific rail line parallel to the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway. The Frisco played a fascinating role in Kirkwood’s development. Oddly, despite the name, it never actually reached San Francisco!

In and Out By Train

The Frisco Railroad was founded in1876, and it was spun off from the Pacific Railroad project. The Frisco ran across nine states from St. Louis to Dallas and even to Pensacola. It had steam locomotives and stylish passenger service.

Running southeast across Kirkwood is a branch or spur of the Pacific Railroad. Yes, I could reach Akron from St. Louis rather directly by 1900.

Finally, the “Dinky” Line was a small train which ran between clay mines in areas like Chippewa and Brannon (nicknamed “The Diggins”) and the Christy factory near Kingshighway. Though not directly in Kirkwood, this shows how short-line rail systems supported clay transport.

So, if St. Louis merchants wanted a rail car load of Akron’s “pills” it was certainly possible to order it. It begs the question: why order these toys from over 500 miles away when you could make them locally out of quality clay?

Arteries of Clay

OK. Kirkwood had an impressive rail system very early in its history. And neighborhoods all over St. Louis shared rail spurs and feeder lines for both freight and passengers. But did St. Louis have clay to ship on these rails?

Yes. The rail lines ferried raw materials from rich clay pits to factories and kilns, becoming veins of industrial transformation. St. Louis communities like Kirkwood and Cheltenham weren’t just bystanders—they were shaped by the rhythm of the extraction and shipment of coal and clay.

St. Louis didn’t just build, make brick and other ceramic with clay, St. Louis dealers shipped it. The city’s clay-rich geology, especially along the Mill Creek Valley and areas like Cheltenham, made it a hub for both raw and processed clay products. While finished goods like bricks were the primary export, raw clay was also transported by rail, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries when demand for building materials surged across the Midwest and beyond.

Railroads such as the St. Louis and Iron Mountain and the Pacific Railroad of Missouri were instrumental in moving clay from extraction sites to processing centers and out to other cities. Cheltenham, for example, became a boomtown partly because its fireclay could be shipped eastward thanks to its rail access[17].

If you are like us then you tend to think of the old depots, roundhouses, and even the modern rail lines themselves as being fixed. While we often imagine rail lines as permanent fixtures etched into the landscape, history tells us a much more fluid story. The historic railroads in St. Louis enabled mobility, connectivity, and innovation.

Beneath Our Feet: Clay Transformed St. Louis’ Industry

Clay wasn’t just a resource in St. Louis; it was an identity. Local economies, employment patterns, and we are confident that even children’s toys (marbles) all flowed from these deposits.

Fireclay deposits in St. Louis were formed during the Pennsylvanian period, which is often found beneath coal seams. This clay was heat-resistant and perfect for bricks, tiles, and terracotta. By the mid-1800s, neighborhoods like Dogtown[18] and The Hill had over 25 underground clay mines.

Kaolin

Yes, there is kaolin clay in St. Louis. It is known for its whiteness, like most of the marbles which our correspondent gifted to us. Historically, as the newspaper story points out, kaolin has been used to make porcelain and high-grade ceramics. And probably low-fired marbles. Even the casual marble collector has almost certainly seen kaolin marbles which are often grouped in lots which also contain stone marbles.

Compton & Dry Pictorial St. Louis Plate 68[20]

Hydraulic-Press Brick Company: A Revolution In Clay

This 1876 map shows a hub for brick production, with companies like the Hydraulic -Press Brick Company shown at the very top of the map just behind what appears to be a tower of some sort. This is just one of the eleven brick yards which Hydraulic Brick operated in St. Louis. This brickyard is on Grand Avenue near the intersection of Chouteau Avenue.

The Hydraulic-Press Brick Company of St. Louis was a powerhouse of 19th-century industrial innovation. It revolutionized brick making by introducing hydraulic press technology, which produced bricks that were denser, stronger, and more uniform than traditional hand-molded ones.

The hydraulic press allowed for faster production and superior strength: pressed bricks could withstand 157 tons of pressure, compared to just 65 tons for handmade ones. By the 1890s the Company was the largest brick manufacturer in the world.

St. Louis bricks were so durable and affordable that they were shipped nationwide to Chicago, to New York, and to the Pacific West. For more information about brick making, see the last section of this story.

We’re Back At Square One, But We Hope A Bit Wiser

Here’s what we are positive about so far. Glass marbles were made in the city by Alox Manufacturing Company, along with other children’s toys, by the 1930s.This introduced marble play to the area. Our next question is: Does or did St. Louis City or St. Louis County have clay plastic enough to mold clay or ceramic products such as marbles? Yes they did. In fact, miners and manufacturers in St. Louis had what was often called an unlimited supply of clay.

The city and county had fire clay; flint clay; burley clay, which is rich in aluminum minerals; diaspore and kaolin; ball clay; loess; alluvial; full and Bentonite! Many of these types of clay would prove to be excellent for making low-fired marbles.

Did workers in St. Louis mine the clays? Yes, they did. In the online paper “The Clay Mines and Factories of Dogtown” faculty at Webster University[21] identify an astounding 93 mines in St. Louis during the clay boom of the late 1800s and early twentieth century!

Of course, a number of these diggings belonged to the Hydraulic-Press Brick Company which processed untold tons of fire brick. Others apparently were small time mines. Smaller operations include the Alley Mine and the Humes mine. The names of many known mines and workings have been lost to time.

So, St. Louis had a surplus of the clays needed to make marbles in quantities or locally for the children of the miners. While exact numbers aren’t recorded, the labor-intensive nature of underground mining—especially in clay operations—suggests hundreds to possibly thousands of miners were employed over time.

Were Local Clays Used in St. Louis to Make Marbles?

Even after all our research, reading and study we cannot say “yes” with absolute certainty. We have not uncovered receipts, bills of lading, nor pay stubs. Hard evidence. But we are left with formal reasoning. Common sense. And experience.

In chapter Three of our book The Secret Life of Marbles (https://www.amazon.com/Secret-Life-Marbles-History-Mystery/dp/B0BMSTV5D/) “Schlepping Off To Jugtown” we detail our long and complicated trip to a tiny ghost community in Georgia where local potters made beautiful pots for the local and national market. The common and widely-held belief was that these potters never made clay marbles, never slipped them in cobalt, and never added salt glaze. They did. Our research was detailed and our trips to Jugtown were bitterly cold, but we proved that local potters did make clay marbles for their families. We are positive that the same type thing happened in St. Louis but on a much larger scale.

The Kirkwood Historical Society (https://www.facebook.com/kirkwoodhistory/), whose members are “stewards of Kirkwood area history and the National Landmark Mudds Grove” told us they had no information about clay marbles made in St. Louis. We have also communicated with the Missouri Historical Society Library staff for several weeks and staff there are still searching for us.

Think about it rationally. Adult mine workers had clay by the ton to work with so they had the means in abundance. They worked with plastic clay all day six days a week.

Big Families & Small Pay

While exact averages for St. Louis aren’t consistently published, census records from the era (ca. 1870 – 1920) show large household sizes, especially in working-class and immigrant neighborhoods. The decline in infant mortality and the rise of public schooling influenced family planning during this time.

Urban families in St. Louis tended to have fewer children than rural counterparts. There was limited housing space in communities like Dogtown and the cost of living was higher in cities.

Immigrant families, especially in German and Irish communities, often had larger households, sometimes exceeding six children, reflecting cultural norms and economic strategies.

Across the U.S., family size peaked between 1860 and 1920, with many households having six to nine children in the earlier decades. By 1920, industrialization, such as hydraulic brick works, and changing roles for women began to reduce family sizes, with two to four children becoming more typical.

Wage data for clay miners in St. Louis between 1870 and 1920 is sparse and often lumped in with broader categories like coal miners or general laborers. But here’s what we can piece together: Unskilled laborers (a category that likely included many clay miners) earned around $0.10–$0.15 per hour, or $6–$9 per week assuming a 60-hour workweek.

Who Set These Wages?

In the early 1900s–1920s Bituminous coal miners — a close occupational comparison — earned about $6.90 per day in 1922, which translates to roughly $60 per half-month. Clay miners in St. Louis may have earned slightly less, depending on skill level and union presence.

Many things influenced the miners’ pay including the type of clay being mined. Fireclay mining, which was prevalent in St. Louis, required more specialized labor and may have commanded higher wages.

The Company the men worked for also influenced pay. The mines in Dogtown, The Hill, and Tower Grove South had varied conditions and ownership, which affected pay scales.

Pocket Treasures: “How Much for Those Marbles?”

–

–

How AI imagines what a bag of store-bought marbles would look like!

If a little girl or boy walked into a Kirkwood general store between about 1870 – 1920 he or she would have a range of marbles and prices to chose from. Imported German clay marbles were valued for their craftsmanship. They were handmade and they cost about a nickel to a quarter for a cloth or paper bag full. Clay marbles from Akron and Alox glass marbles cost about three cents to fifteen cents a bag.

Generally there were about 25 – 50 marbles in a bag. And of course price varied based on the marble quality and finish.

Cheap Isn’t Always Inexpensive

When we first looked at the cost of marbles we thought that they were cheap enough that anyone could buy them. Then we dug a bit deeper. Unskilled laborers, including clay miners, typically earned[23]:

1870s: ~$0.15/hour → ~$9/week (60 hours)

1890s: ~$0.15–$0.20/hour → ~$9–$12/week

1910s: ~$0.22–$0.30/hour → ~$13–$18/week

A father had to work about an hour to earn one bag of store-bough clay marbles! On the other hand the marbles that the fathers made and brought home, called commies, were 100% free and virtually unlimited!

Now let’s see how much of the workers’ salary went for food. The average grocery cost at the time was $2.50–$3.50. In the 1870s the average family spent 28% of the miners’ income on food; the cost had dropped to 23% in 1910.

Means, Motive, And Method

So far we know that the miners had the means, the clay in abundance, and the motive, to save money on marbles which would probably just be lost or won by better players, and they had the method. We have no doubt that the skilled brick makers would know how to roll marbles and fire them in those giant kilns.

We are confident that workers did make clay marbles in St. Louis and we are also sure there were lots of them scattered among the families in communities all over St. Louis.

While there’s no direct documentation of large-scale marble production in St. Louis, it’s highly plausible that children or factory workers made clay marbles from leftover material. This was common in other clay-producing regions. Small potteries, like the ones in Jugtown, Georgia, or domestic producers doubtless crafted marbles for local use, especially given the abundance of suitable clay and the popularity of marbles in the 19th century.

In fact, the plasticity and fine texture of the Cheltenham fire clay would have made it perfect for hand-rolled marbles, which were then sun-dried or kiln-fired.

If you have any information to confirm about St. Louis clay marbles, please click the “Comment” button to share your ideas! We look forward to hearing from you.

The Rest of the Story

Some sections of this story point you to read more about related topics. Below is extended information.

Alox Company

Since a large part of Alox history involves shoelaces rather than marbles, we share below information about other products and manufacturing processes.

John Frier was the St. Louis Shoelace King. In October 1919 he obtained Patent US-1318745-A[8] “… and he created a company to manufacture and sell shoelaces. He named the company Alox…because it was different from all other local manufacturing concerns in St. Louis—and would be right at the front of the phone book.” Jeff Duntemann, who spoke with Nancy Frier, the granddaughter of John, while writing his story “John Frier: American Inventor”[9], thus gives one other possibility for how the company was named.

Aluminum Oxide

One other thing about the name Alox for Frier’s lace tips: Alox, Aloxide, and alundum are all names used for aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃). When we studied Frier’s patent we wondered what the shoelace metal tip was made from—was it metal made from aluminum oxide[10]? The patent doesn’t say, but Frier was a gifted and inquisitive inventor.

The actual metal used in the tips isn’t specified in surviving records, but it’s likely they were made of common crimpable metals like aluminum or tin, not a proprietary alloy called “Alox.” But we will probably never know for sure.

We understand that Frier also worked hard on the braiding process for the laces. Their slogan was “Good Shoe Laces for a Nickel; Better ones a Dime.” And with Alox you could: “pull as hard as you like but Alox laces never break.[11]”

About St. Louis Clay

Brick kilns were especially prominent in the 19th century, when St. Louis became a national hub for brick production. Companies like the Hydraulic Press Brick Company used large-scale kilns to fire clay from local deposits. There were dozens of kilns, like the one in this old line drawing[19], and, according to the literature, there may have been hundreds of such kilns scattered across St. Louis.

We found a fascinating story about St. Louis clay tucked away in this 1888 issue of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. It is a long story titled “Fire-Clays of Missouri”. The lead under the head reads: “An inexhaustible supply of peerless raw materials—manufacturers of glass pots, fire-brick, gas retorts, fire proofing and culvert pipe—millions of dollars invested in the Cheltenham District.”

Millions invested in one single community? If true, that would equal about $34 million in today’s money!

Clay marbles or other clay toys are not mentioned in the news story. But with clay so rich we believe that clay workers must have been made, possibly for the worker’s family, locally.

Deep in the 1888 story we learn some startling facts. “…The clay here is unlimited quantities and in quality sufficient for its best uses. It is our own fault that they have not been used.” The story goes on the propose that kaolin clay, and its many uses, was introduced to the British by an American!

How Bricks Were Made

Miners extracted the clays, but that was only the start of the job in the clay works . The raw clay was then processed. Of course, some mines used the latest technology to make brick, and some companies innovated and modified the technology for their own purposes. But for many workers the old ways persisted. Webster University faculty tell us that:

The Fire Clay was soft, white, and porous. It was removed like chunks of coal. It then could be set aside up to five years, then crushed and mixed with other clay. I suppose you could say it was mixed into a cement like mixture. In the old days master molders would form the bricks by hand by the thousands.

While hand-made brick was not as hard as hydraulic brick, these brick companies did compete in the market and they did very well! Tons of these hand-made brick are in buildings still standing all over St. Louis.

In later days mass production was introduced and then the bricks were made by the millions. I’m sure men had to be involved in preparing the material, but just used fewer men. The main tasks were: “setters and burners” who placed the green bricks into the kilns, The “firemen” who kept the fires going, The “off bearers” who wheeled away the brick after baking. Terra-Cotta took more hands on work. This reminds me, about the choice to make fire brick instead of great china. The regular bricks only needed the shale clay. But the fire clay was claimed to be as good as any in the world. So the easy, cheaper way went to fire brick, instead of beautiful dishes[22].

Microsoft Copilot tells us that this is what the clay, sweat, and skill of a bygone artisan might look like

Where to Dig Deeper

If you want to dig deeper into some of the topics in this story, here are some good places to check.

City of St. Louis Historical Maps Collection

This official city archive includes zoning maps, contour maps, and planning documents from the mid-20th century. These are especially useful for tracing urban development and land use changes.

Dogtown Bibliography of Materials @ Dogtown project: bibliography of materials

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dogtown,_St._Louis

https://www.flexfilm.com/alox-coated-films.php

https://www.gearpersonal.com/victorinox-alox/

https://www.westvirginiamarblecollectorsclub.com/alox

http://www.romeofthewest.com/2009/05/clay-mines-of-saint-louis.html

http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/dogtown/claymines-sas.html

https://quarriesandbeyond.org/states/mo/mo-clay_stone_lime_sand_indus_st_louis_1890.html

https://www.stlmag.com/Uncovering-Clues-to-Life-in-19th-Century-St-Louis/

https://patch.com/missouri/stcharles/archaeological-dig-starts-at-historic-site-in-st-charles

https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/SmallFinds/Marbles/index-marbles.html

https://andystoys.com/StLouis.cfm

FRASER’s coal mining wage reports

Missouri Historical Society’s mining archives

Old Maps Online – St. Louis Collection

A treasure trove of digitized maps from the 18th to 20th centuries, including:

1780 Norbury Wayman reproduction of the original French village layout

1874 and 1877 Mitchell maps

1901 Eugene Murray-Aaron map

Plank Road Site, St. Charles (just northwest of St. Louis) Archaeologists from Lindenwood University and the University of Missouri–St. Louis uncovered clay marbles during digs at the historic homestead of Louis Blanchette. The site has yielded artifacts dating back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, including bullets, pottery, and toys.

Rome of the West’s clay mining history

St. Louis Genealogical Society Map List

Offers access to early ward maps and surveys, including the earliest known complete survey of St. Louis County. These are ideal for contextualizing archaeological finds or tracing neighborhood histories.

St. Louis Public Library – Geography & Travel Resources

Their collection includes detailed neighborhood maps and historical atlases, often with high-resolution scans available for research and publication.

The 1925 St. Louis City Directory, published by Polk-Gould, is digitized and available through the St. Louis County Library Collections. It includes alphabetized listings for residents and businesses, along with a buyers’ guide and street index.

Unseen STL History Talks: Digging Deep: Coal, Clay, and Immigrant Miners

Worthy Women’s Aid and Hospital Site (North of Cass Avenue, St. Louis)

Excavations led by the Missouri Department of Transportation unearthed a trove of 19th-century artifacts, including hand-painted porcelain, glass, and clay marbles. These were found alongside dolls and toys, indicating their use by children in a shelter for impoverished women and their families. See https://www.stlmag.com/Uncovering-Clues-to-Life-in-19th-Century-St-Louis/

References

- He or she has requested anonymity in this story. ↑

- “I googled” is considered proper English—especially in informal contexts. The verb to google was officially added to dictionaries like Merriam-Webster and the Oxford English Dictionary back in 2006, meaning “to use the Google search engine to obtain information”. We understand that Google isn’t very happy about the generic use and they feel that it may weaken their trademark. ↑

- https://marbleconnection.com/joemarbles/2Manufacturers%20History%20Pages/03Alox/Alox%20Manufacturing%20Company.html 7/16/2025 ↑

- With a nod to Ray Parker. ↑

- 1920 St. Louis City Telephone Directory (1920), [411014-C]. St Louis County Library Collections, accessed 19/07/2025, https://slcl.recollectcms.com/nodes/view/706/ (7/18/2025), 1922 St. Louis City Telephone Directory | St Louis County Library Collections 7/17/2025 ↑

- 1925 [A] St. Louis City Directory (1925), [1925-STLCity_04]. St Louis County Library Collections, accessed 19/07/2025, https://slcl.recollectcms.com/nodes/view/4000/ (7/19/2025). Alox listed on page 6 of the following section of the [A-B] St. Louis County Directory 1926↑

- https://www.countyoffice.org/cockrill-st-saint-louis-mo-property-records/ and https://www.realtor.com/realestateandhomes-detail/1335-Cockrill-St_Saint-Louis_MO_63133_M91177-49515 Both 7/20/2025 ↑

- The Patent is for a metal shoestring lacing tip. Metal tips were not new, but, according to the Patent, Frier’s was both new and improved. ↑

- https://jeff-duntemann.livejournal.com/157301.html? (7/19/2025). You might also want to check https://www.brandlandusa.com/2010/06/16/wear-st-louis-alox-shoe-laces/, https://buymarbles.com/marblealan-alox.html, https://kitelife.com/2010/08/01/issue-73-alox-kites-and-the-man-who-made-them/ All three checked on 7/19/2025 ↑

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Aluminum-Oxide; https://www.americanelements.com/aluminum-oxide-1344-28-1; and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aluminium_oxide 7/19/2025 ↑

- https://www.brandlandusa.com/2010/06/16/wear-st-louis-alox-shoe-laces/ 7/20/2025 ↑

- These little canes are very collectible and we have bought a few in antique shops over the years. We never researched them, but we thought that they were Japanese or even German. We are delighted to learn that Frier at Alox may have made them. Each is a nostalgic artifact from early 20th-century American fairs and carnivals, often given as prizes or souvenirs. These canes weren’t walking sticks—they were meant for children as tokens of celebration, flair, and sometimes a bit of kitsch. ↑

- https://kitelife.com/2010/08/01/issue-73-alox-kites-and-the-man-who-made-them/ (7/19/2025). There is an interesting story about why Frier turned to making marbles rather than buying them wholesale. It is told by his Granddaughter Nancy L. Frier in her story in Antique Week: “…Originally, Alox only manufactured the boards for these games and bought the needed marbles.” However, the company ran into a problem with their marble supplier. It seems marbles are sold by weight and the marble wholesaler had taken to filling the bottom of the boxes the marbles were shipped in with chunks of broken glass. Frier decided to make his own. Frier bought seven marble making machines from West Virginia, with two of the machines running any given time. The marble machines at ran 24 hours a day, six days a week.” Of course, that broken glass was cullet but it was useless without a marble machine. The cullet increased the marble weight and it effectively overcharged Alox. See https://www.antiqueweek.com/ArchiveArticle.asp?newsid=1815 7/20/2025 ↑

- St. Louis City and St. Louis County are completely separate entities. In fact, St. Louis is one of the few cities in the U.S. that’s not part of any county. This split happened in 1876, when voters approved the “Great Divorce,” making St. Louis an independent city with its own government, separate from the surrounding county. St. Louis City is roughly 66 square miles, governed independently while St. Louis County is much larger, with over 90 municipalities like Kirkwood, Clayton, Florissant, and University City — but not including St. Louis City. ↑

- See John F. Stover, The Routledge Historical Atlas of The American Railroads, NY: Routledge, 1999, especially pages 22-23, 98-99, and 110 -111. Also https://www.american-rails.com/mo.html; https://www.kirkwoodmo.org/government/departments/administration/historic-kirkwood-train-station-restoration/; “The Kirkwood Cutoff” @ https://www.abandonedrails.com/kirkwood-cut-off/; and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirkwood_station_%28Missouri%29 All links accessed 7/21/2025 ↑

- “Map of Kirkwood Missouri” http://collections.mohistory.org/resource/1149792 Identifier Lib366 ↑

- https://blog.stlouisbank.com/the-bricks-that-built-st-louis/; https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/planning/cultural-resources/preservation-plan/Part-I-Transportation.cfm/; and https://www.umsl.edu/mercantile/barriger/mo-rrs.html All accessed 7/25/2025 ↑

- We would be remiss if we didn’t mention Dogtown. Hydraulic-Press operated its Yard 2 at the junction of Manchester Avenue and Kingshighway right in the heart of Dogtown. “Dogtown” isn’t an official neighborhood name, but rather a beloved local term that refers to a cluster of neighborhoods in southwest St. Louis, just south of Forest Park. Historically, it was a clay and coal mining community in the mid-1800s, and the name “Dogtown” was commonly used by miners to describe clusters of shelters near mines. Communities in Dogtown include Cheltenham which once had over 50 brick yards and 213 kilns. The glow from these kilns lit up the night sky. And tunnels ran all under Dogtown—Cheltenham had over 70 miles of tunnels in the city and 20 miles in the County! If you’re at all interested in Dogtown you really need to check out “Bibliography on Dogtown and Related Subjects” published by Webster University [https://www.webster.edu/] @ http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/dogtown/biblio.html/ ↑

- St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Sunday, January 8, 1888. ↑

- Compton, Richard J, and Camille N Dry, Pictorial St. Louis, the great metropolis of the Mississippi Valley; a topographical survey drawn in perspective A.D. St. Louis Compton & Co. 1876. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/rc01001392/>. ↑

- http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/dogtown/claymines-sas.html 7/25/2025 ↑

- “The Workings” @ http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/dogtown/claymines-sas.html 7/27/2025 ↑

- AI Copilot helped us collect these figures which are from wage tables compiled by the National Bureau of Economic Research and historical labor reports. ↑