Smithsonian Open Access|Smithsonian Institution[1]

Have you ever heard a story or read an anecdote in a book, magazine, or online which you then could not get off of your mind? Hopefully, that happened with one of our stories! While later searching or just browsing online or while working on a project with your marbles, have you ever had what psychologists call a spontaneous mental recall about the story?

You probably are more familiar with musical ear-worms. In this case you get just a thread of music stuck in your head, or a catchy tune, and you keep thinking about it.

Well, the same thing sometimes happens to us after we publish a story. This eMagazine is about marble secrets, mystery, and history. And consequentially very few of our stories are ever actually “solved” when we wrap up all the data and evidence we have at the time.

“On the Road Again”[2]

One story which is often on our minds is the one about marbles made at the Iowa City Flint Glass Manufacturing Company in the early 1880s. We first visited Iowa City in our story “Were Victorian Sulfide Marbles Made in America?’ (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/sulfide-marbles/). Yes, there is strong circumstantial evidence that sulfides, other glass marbles, and decorative glass canes or whimsies were made in Iowa City in the early 1880s. This belief is held by some marble collectors, and marble sellers, both here in the United States and across Europe.

Circumstantial Probabilities

Circumstantial evidence is critical to our Iowa City case. According to Cornell Law School, circumstantial evidence does not prove a fact in issue (were sulfides and other marbles made in Iowa City for example?), but it does give rise to a logical inference that the fact exists.

These probabilities are critical in many civil and criminal cases. “In fact, most of the evidence used in criminal cases is circumstantial….most criminal convictions are based solely on circumstantial evidence…. If direct evidence were always necessary for a conviction, a crime would need a direct eyewitness, or the guilty party would avoid criminal responsibility.”[3]

No one can say “I saw this glass cane and this glass marble made in the Iowa City glasshouse.” Still, in our opinion, the circumstantial probabilities are too obvious not to accept.

A Bit of Review

Iowa City Flint Glass Manufacturing Company was established in April 1880. We know exactly where it stood. In our first story about Iowa City Glass (ICG) we relied heavily on Miriam Righter’s book Iowa City Glass. It is the only one we can find about the Company.[4]

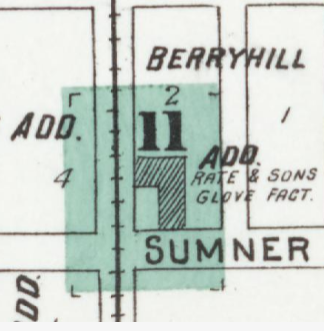

Righter tells us on page six that: “The location of the factory was the south half of Lot 6, and Lots 7, 8, 9 and 10, Block 2, Berryhill’s First Addition. This legal description refers to the area lying to the north and east of the intersection of Maiden Lane and Kirkwood Avenue in Iowa City.” To see an historical image of the Company check “The Iowa City Flint Glass Mfg. Co. 1881 – 1882” (https://www.patternglass.com/Factory/IowaCity/index.htm).

When ICG closed in the summer of 1882 the plant stood empty until 1891. There was litigation with respect to ICG until 1887. In 1891 the E.F. Rate and Sons Glove Factory opened in the old glass house. Righter explains that the Rate family did not alter the glass factory except to resurface the front section with brick (page 16).

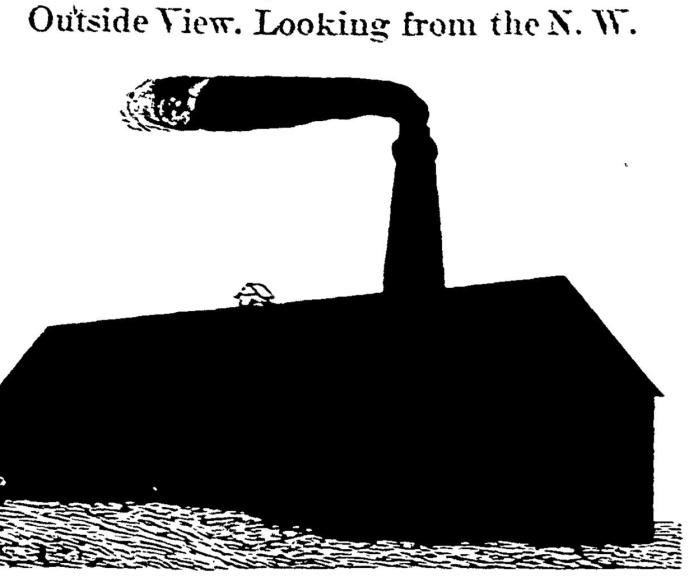

Plate 1 in Righter page 36 is the same image of the glass factory as the one that appears in the story “The Iowa City Flint Glass Mfg. C. 1881 – 1882”. [5] Plate 2 page 36 shows the same factory after the Rate family bought it and started glove manufacturing.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map

Although we searched diligently at the Library of Congress, we could find no Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for the Berryhill’s First Addition during the years that ICG was in operation. We did, however, find a Sanborn map showing Rate’s Glove Factory in 1892.[6]

The factory burned in 1898 and all that was left was the large stack and the stone foundation. The factory may have been struck by lightning . It probably burned more than once. When Righter started work on her book about 1953 or 1954, she spoke with a number of “old-time residents” who remembered the factory fires.”

The factory stack was in the top of the inverted “L” and toward the railroad or sideline.

As an aside: we have been told by reputable marble collectors that in the case of Iowa City Glass our “history” is only the talk of old men. Well, we have both studied and listened to the talk of old women and old men, and we have learned historical truths which the history books don’t contain. And sometimes if this wisdom is not captured and written down then it will be lost forever.

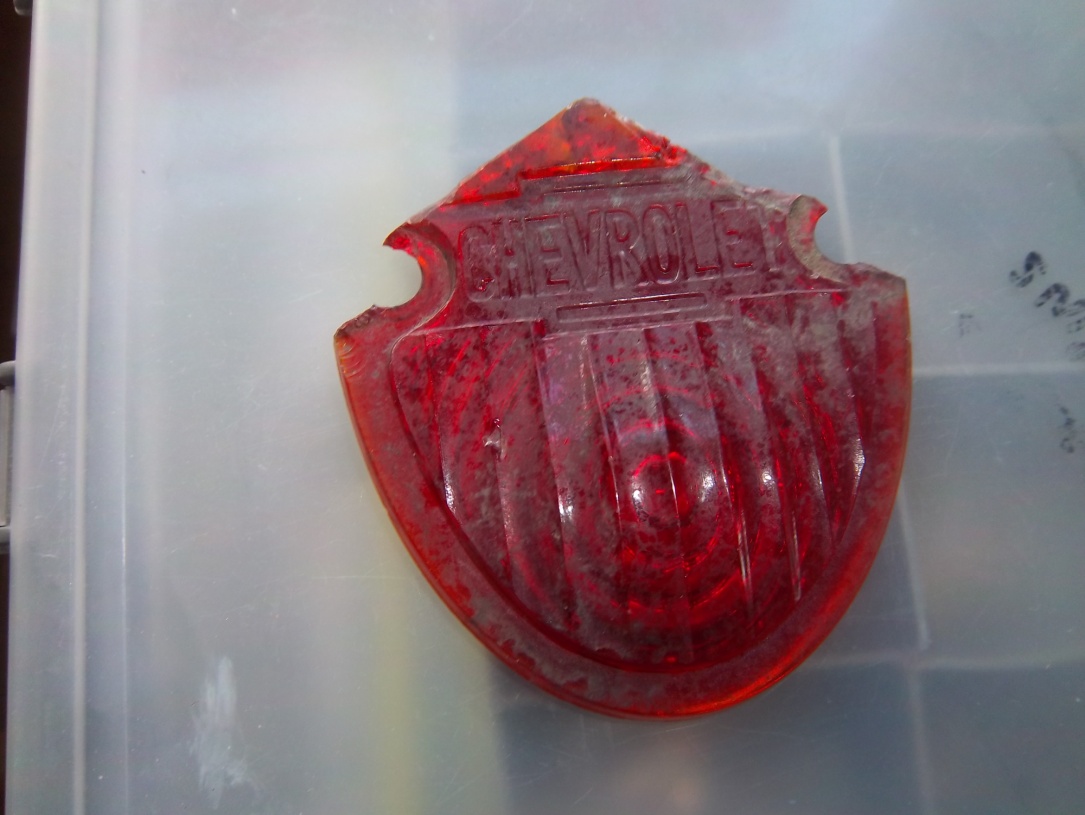

1930s Chevrolet Tail Light Assembly Used to Make Red Striping on Vitro Agate Marbles

Circumstantial and Direct Evidence

We all know that cullet or scrap glass is included in marble and glass making. Many of the 20th century marble makers in West Virginia used glass scrap as one of their primary ingredients. They sourced tons of glass scrap from outside their own factory. Cairo Novelty Company, for example, bought glass scrap from a vendor in Washington, Pennsylvania. And, of course, marble and glass makers also used cullet from their own operations to make additional products.

Righter has photographs of Iowa City scrap, and one photograph of her and her family members digging and collecting glass sherds at the Iowa City factory site. She also discusses cullet both found and dug at the ICG factory.[7]

Digging Cullet at the Gas Station

Plate 4 page 37 is a photograph of the gasoline station which was built on the site of the ICG, and the glove mill, although we are unsure of the exact timeline. In the photograph of the family digging is a large black tank, like those buried at gasoline stations, which sits on the ledge beside the deep hole that they are exploring.

The glass cullet at the site of the ICG factory is direct evidence that glass was made onsite at one time. However, Righter is far from naïve about the glass sherds. She writes that “there are those who claim that sherd gathered from the site of a glass factory cannot be accepted as proof that a particular type of glass was produced by that factory (pages 17 – 18).”

All of us who have searched glass marble sites are aware that collectors can expect to find Cairo marbles, for example, on the Heaton site. Just because an Alley Agate is found in Champion cullet does not prove, for example, that Alley glass was made on the Champion machines.

Righter continues that “…it would be equally wrong to assert that none of the factory’s own product was likely to turn up in the sherd.” If Righter found marble fragments, marbles, or missforms in the sherds at the gas station then she doesn’t tell us.

Who was J.H. Leighton?

Who was James Harvey Leighton? “What an inane question” many would ask. Marble collectors everywhere, and most who just have a love of marble history, know that Leighton held US patent US462083A for the “Manufacture of Solid Glass Spheres” which was issued on October 27, 1891. This was the first patent issued to make toy glass marbles by machine instead of by hand.

And many also recognize the links between Leighton and Samuel C. Dyke, who produced the first mass-produced toy marbles in America. Dyke made clay marbles and he opened his factory in Akron, Ohio, in 1884. Perhaps you don’t realize, however, that in 1891, the same year that Leighton was granted his patent, he also worked for Dyke in Akron. “Dyke also produced handmade glass marbles in Akron. In 1890, he hired master glass maker James Harvey Leighton to train workers in making glass marbles.”[8]

“Go West Young Man”

Leighton’s successes in Akron were ahead of him when he first travelled the long and dusty roads west seeking his fame and fortune. He was born February 18,1849, in Connecticut.

Righter infers that Leighton was probably in Iowa City in the summer of 1880. He was one of the many incorporators of ICG and is described by Righter as the factory manager and glassblower. Perhaps he also made molds for some of the pattern glass. Or perhaps he brought molds with him to Iowa City. He is also referred to as the superintendant of the glass factory.

A Family Tradition?

He was a member of the Leighton glass family which had about 65 years of glass experience when Leighton went west. There remains a good deal of marble history and mystery surrounding J.H. Leighton’s exact place in the extended Leighton family. But we are certain that William Leighton was also in the long line of Leighton glassmen.

Did you know that William Leighton held a number of US Patents? One that we find fascinating is for glass knobs: for drawers and doors (US12265A)! This was in 1855 when William was still living in Cambridge.

While he was believed to be an excellent professional Glassman, there was a bit of confusion among the locals in Johnson County about exactly who J.H. Leighton was when he arrived, and then soon left again. The document “The Iowa City Flint Glass Mfg. Co. 1881 – 1882”[9] tells us that J. H. Leighton was the grandson of Thomas H. Leighton, Sr., who had seven sons and six of them were glassmen. This article also explains that J. H.’s father was John H. There are more details in the story. Really?

Who’s Your Daddy?

Perhaps. On the other hand, WikiTree tells us that John Harvey Leighton’s (1849 – 1923) father and mother were Peter Hill Leighton and Cecelia Catherine (Smith) Leighton.[10] WikiTree also explains that he was the brother of Ann Leighton, Cecelia Elizabeth (Leighton) Hanes, Emily (Leighton) Garrignes and William Leighton. But of course, William, his son, could not have patented glass doorknobs!

So, we are left with almost as many questions and mysteries about Leighton as when we started.

“Trouble in Iowa City”

“Trouble…” is the name of one section in our post “Were Victorian Sulfide Marbles Made in America?” (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/sulfide-marbles/) and we will not go into the shenanigans in the little mid-western town again here. To say the very least, however, the reverberations and repercussions, and the financial impacts, lasted long after Leighton headed back east.

In this post we are exploring the background and the contributions of J.H. Leighton to the Iowa City Glass venture and he was in town for the entire short life of the Company.

Linda Yoder has contributed a story unlike any other that we have ever seen about Leighton and the Midwestern glass towns. “Glass Factories on the Iowa Prairie” was published online by the Early American Pattern Glass Society (http://glass-museum.com/early-american-pattern-glass-society.html). One of the two towns that Yoder considers is Iowa City and another is the nearby town (about 35 miles away) of Keota in Keokuk and Washington counties.

Keota

Yoder tells us that “in 1879 the Eagle Glass Works was established in Keota, Iowa. It was the first glass factory built west of the Mississippi River…. The factory produced dinnerware, barware, jars, lamp chimneys, utilitarian pieces and glass novelties.” We wonder, but really have no idea, what the “novelties” were. Clay and glass marbles were often sold at the time as novelties.

You can see images of the glass produced at Eagle in the State Historical Museum of Iowa in Des Moines.[11] If marbles are in the lot of 25 or so pieces then we could not find them. On the other hand, you can compare Iowa City pattern glass to Eagle Glass digitally at the Museum.

A New Venture

We found information about Eagle Glass in the newspaper Keota Eagle page 2, September 6, 1879, in the Library of Congress “Chronicling America”. However, a much easier site to work with (and much easier on your eyes) is online at the Keokuk County IAGenWeb.[12] Eagle Glass Works was not built along the same design as the glass factory in Iowa City. The Eagle building was 104 feet long and 50 feet wide.

Here is what was written in the newspaper about the plans for the glass works: “We have an entirely new and full outfit of molds for making table ware, lamps, &c. These styles and patterns were designed by Mr. [James Harvey] Leighton, and are such as will recommend themselves to the trade. It is the intention of the Board and the Manager to make Keota Glass popular with the dealers and among the people. They will send out nothing that will not bear the closest scrutiny.” The factory close in 1880.

A Dreamer & a Con Man

A Dreamer & a Con Man

Remember that we mentioned Linda Yoder? Here is more of her story: “J. H. Leighton, born in Boston Massachusetts, February 18, 1849; was an enterprising young glassblower who worked at Hobbs Brockunier & Co.” Hobbs was one of the biggest and best known glass firms in America in the 19th century. Remember, WikiTree tells us that Leighton was born in Connecticut.

From Hobbs, Yoder continues, Leighton “…went to Harpers Ferry, Ohio, to remodel and take charge of the old Excelsior Glass Works, renaming it the Buckeye Glass Works, where he worked until 1878.[13]

Leighton didn’t stay at any one factory for an extended period of time. With the west rapidly developing he must have decided that would be an excellent area to build a glass factory. What attracted him to Iowa? Was he trying to make a name for himself within the Leighton family and in the glass works industry? Was he looking for a quick way to make a fortune? Did he think glassware could be made cheaper in Iowa than in Eastern States?”

One More Thing….

We cannot prove this next fact by Yoder: Leighton worked at or was Superintendent of more than 20 glass works. We are aware of Keota and Iowa City, and we have a passing acquaintance with a factory start-up in Oskaloosa, Mahaska County Iowa, but we have no intention to attempt and ferret out 18 more shops!

We will conclude our quotes from Yoder with this and let you read the rest of her story should you wish: “…he appears to not be very reliable or stable. He was a good glassman but not a very profitable manager or owner. Some accounts characterized him as a dreamer and con man!”

Hard Working Glassman & Entrepreneur

We doubt that anyone alive today knows why Leighton “broke the mold” in the East and traveled west to work in glass. We wonder if anyone really knew or explored his motives at the time. But the last time we checked Webster’s we read something like this about the term “con man” or “con artist”: an individual “who cheats or tricks someone by gaining their trust and persuading them to believe something that is not true.”

We will concede that Leighton was a dreamer. He wanted to make glass west of the Mississippi and we believe that he made a sincere and good-faith effort to do just that. His family had been in glass for decades. He knew that a good solid living could be made from glass, but we simply will not accept that he believed that anyone, even someone as talented as himself, could make a quick fortune in glass: in Iowa, Massachusetts, or any ferry town in West Virginia or Ohio.

Mistakes Were Made Aplenty in Iowa

We have now studied this situation for hundreds of hours and doubtless longer than anyone else. We believe that we do know what happened out west. First, in Keota and then in Iowa City. We will not dwell on the geology nor the glass recipes used, but we are confident where the downfall lies.

First, there is this key mistake from the Keota Eagle, which was a major investor, which lent the glassworks its name, and which is mentioned above: “Mr. J. H. LEIGHTON, a noted glass maker of Wheeling W. Va., is Manager, and all the work has been done according to his directions. Whatever he wanted done, he either did himself, or told some one else how to do it. He has experience of two or three generations of glass makers, besides having been Manager of some of the largest and best factories in West Virginia, Ohio and Pa. He knows the whole business by heart, and has managed the construction of these works without making a single mistake.”

How could Leighton or anyone else live up to this hype? The same sort of things were written in Iowa City. And, of course, while the factories were being built and operated talk like this was always rampant.

A Four Letter Word

We wrote a good deal about glass making in our post “The Laischaer Glashütte & the Origins of Modern Glass Making” (https://thesecretlifeofmarbles.com/modern-glass-marbles/).[14]

Sand. That is the four letter word in the Iowa City area. Either there was no glass sand in the Skunk and English Rivers in Keota or the Iowa River and Raccoon Creek in Iowa City or there was too little silica sand[15] and too much sand of poor quality for glass making.

Righter agrees with our assessment: “…one of the primary sources of difficulty was the discovery that the sand in the Iowa City area was not suitable for glassmaking, in spite of the fact that it had been tested in advance. This meant that it would be necessary to transport sand from …some other point distant from Iowa City. (page 13)” How, in 1880, and where could he have the sand analyzed? We do not believe that he intentionally used poor silica sand; we simply believe that mistakes were made all around in Iowa.

What Did This Mean?

The lack of sand meant higher transport costs, and possible shipment delays. The sand problem would also mean that the Iowa City factory could not produce as high quality flint glass, and this in turn could have forced both factories into a restricted market outside the mainstream competition and at lower prices.

Competition with Eastern established companies was always fierce and unforgiving. When freight rates went up Iowa City and Keota Eagle saw their thin profit margin decline even more.

We have not mentioned it in this post, but the labor market was in flux while the factories were in operation. Some believe that workers were sent from the East expressly to “sabotage” Iowa City. And it is a fact that very few of these men were interested in settling down in Iowa and contributing long-term to the communities.

“They were reported to be heavy drinkers, given to spending most of their free time in the local saloons, gambling and carousing.”

Leighton’s Last Stand

So we close this first section of our post. We feel that our analysis of the 1880s glass produced west of the Mississippi has been well covered. We also believe that we have been fair and honest about an often riotous time in American glass-making history. We cannot imagine that we will ever go back to our resources and then write more about it. To our knowledge it isn’t recorded when Leighton left Iowa City and headed back East.

WikiTree tells us that in the 1900 US Census he was living in Middlebury Township, Akron Summit, Ohio, with his wife Alda and seventeen year old son Richard. We find it interesting that Alda was born in Iowa.

Leighton died on the 9th of February 1923 at age 73. WikiTree tells us that he died in “Wheeling, Ohio [County?], West Virginia.” We studied his death certificate. He died of pneumonia complicated by an acute cold. But we’re not done with Leighton yet! There is more to his story: There is another post to follow which covers the manufacturing of marbles and glass canes at Iowa City Flint Glass.

Footnotes

- @ https://www.si.edu/openaccess (11/9/2023) Special thanks to Riche Sorensen, Rights & Reproduction Coordinator, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Notation on cane: “Green Glass Cane: 1910s.” Maker unknown. Record ID:saam_1986.65.18. ↑

- With a tip of the hat to Willie Nelson who wrote and sang this catchy tune as the 1980 theme song for his first leading role in the Jerry Schatzberg film Honeysuckle Rose. Story is that Willie wrote the song “on the fly” and on an airplane barf bag! Admit it, now we’ve given you an earworm, right? ↑

- https://www.egattorneys.com/circumstantial-evidence-in-criminal-cases (11/12/2023) ↑

- Righter, Miriam. Iowa City Glass NP; nd; © 1981 Dr. J.W. Carberry. ↑

- https://www.patternglass.com/Factory/IowaCity/index.htm 11/20/2023 ↑

- This detail is from “Image 1 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Iowa City Johnson County, Iowa” April 1892 Sanborn=Perris Map Co. limited. @ Image 1 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Iowa City,Johnson County, Iowa. | Library of Congress (loc.gov) 11/20/2023 ↑

- Plates 5, 6, and 7 pages 38 – 39. This photograph, which does show marble scrap and patterned glass, is from the collection held at the State Historical Museum of Iowa, Des Moines. The accession number for this lot is 1630 and this is the description with the cullet: “1 of 26 glass sherds and pieces of slag in an assortment of shapes, sizes, and colors including clear, blue, green, lavender, white, and gray. Dug up from factory site of the Iowa City Flint Glass Manufacturing Company, circa 1880-1882.” Courtesy of the State Historical Museum of Iowa. Special thanks to Kay Coats, Collections Coordinator, State Historical Museum of Iowa @ https://iowa.minisisinc.com/scripts/mwimain.dll/126481118/3/0?SEARCH&DATABASE=COLLECTIONS&SIMPLE_EXP=Y&ERRMSG=[IOWA_root]no-record-collections.html/ (11/21/2023) No contributor is listed and we are left to wonder if Righter donated these sherds to the Museum. ↑

- https://www.neatorama.com/2010/11/03/neatolicious-fun-facts-marbles/ 11/22/2023 & 11/24/2023 ↑

- https://www.patternglass.com/Factory/IowaCity/index.htm 11/24/2023 ↑

- https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Leighton-1550/ 11/24/2023↑

- https://iowa.minisisinc.com/scripts/mwimain.dll/125563082?UNIONSEARCH&application=union_view&language=144&SIMPLE_EXP=Y&report=web_union_sum_report&ERRMSG=[IOWA_root]no-record.html 11/24/2023 ↑

- There is a wealth of information on this site including a photograph of a $50.00 share in the stock. @ http://www.iagenweb.org/keokuk/histories/keotacent/pgs_71-80.html 11/24/2023 ↑

- The last time that we were in Harper’s Ferry it was in Jefferson County, West Virginia. The Vaseline Glass Collectors, Inc. tells us this: Buckeye Glass Co.: This company was founded in 1878 in Martin’s Ferry, Ohio, by wealthy capitalist, Henry Helling. John F. Miller was the Secretary before Helling purchased the factory from Excelsior (Glass)Works and changed the name. In 1887, Harry Northwood joined as General Manager. In 1888 … Miller left the company, but returned in 1891, and he was known to have been at Model Flint Glass Co. in 1901. ↑

- You might also want to check “What Goes into the Making of Glass?” by David Adams @ https://www.stretchglasssociety.org/the-making-of-glass ↑

- You might want to check “What kind of sand is used to make glass?” @ https://www.quora.com/What-kind-of-sand-is-used-to-make-glass 11/27/2023↑