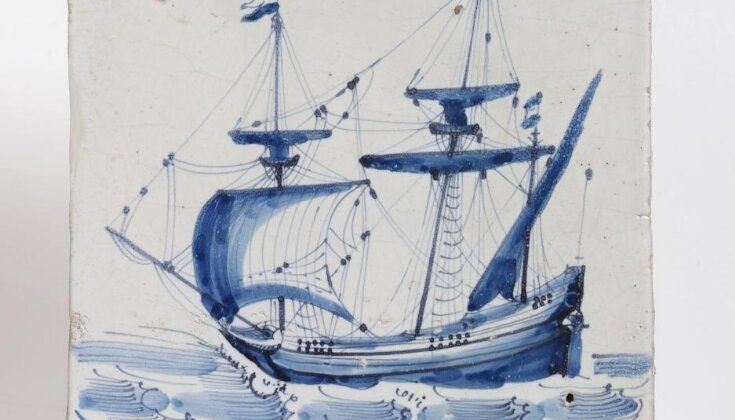

Wall tile, Harlinger, Netherlands, 1650-1700 Tin-glazed eathernware with painted decoration in blue with manganese outline, a ship. Image ID 2007 BN2966. Accession No. C.569:2-1923. Victoria and Albert Museum, London Collectibles, London. [11]

An Old Broken Jar

When we lived in Kissimmee, Florida, we loved to explore and antique in nearby towns. We made good friends with Justin[6]. He is a gentleman who owned a coin shop in Lake Hamilton Florida. We asked him to be on the lookout for marbles for us. He regularly travelled to several states to buy coins and estate sales and he said that sometimes he did run across marbles although he knew nothing about the ones he saw.

He started to add marbles to his stock. Most were Vacor. In late March 2014 he told us about a jar of marbles which he bought recently. He had no background on the marbles, but said that it took him some forty-five minutes to get through the red rubber seal without breaking the jar. The jar is old (we did not buy it), and the seal dates it to the mid 1930s. Evidently, it had not been opened in all that time.

Justin poured the marbles out in a tray, and they appeared dusty and obviously hand collected from the surface or dug. It was extraordinarily difficult to identify what we were looking at. We could identify Bennington slip, and lots of stone. In fact, in the Shop we thought one or two stone

What We Got?

We negotiated price and Justin kept the antique jar. He let us pay him what he paid for the jar and marbles. All he wanted was the antique jar, but we found out in the shop that it was cracked. None of us broke it, but it literally came all to pieces.

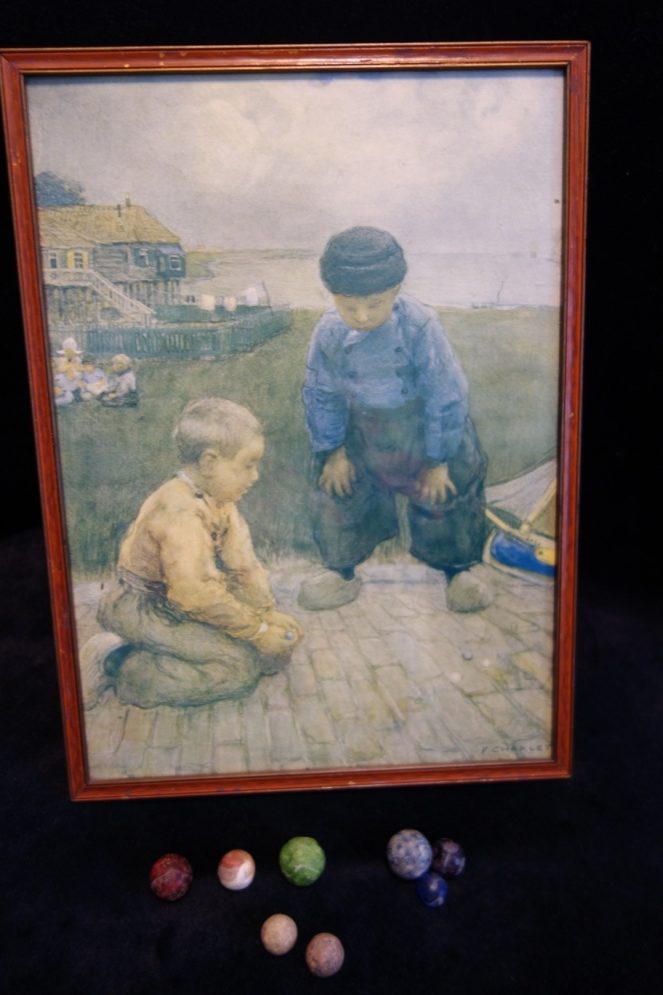

At home we examined the marbles for several days, and we grouped them into types to facilitate analysis.[7] At first we thought the marbles, although sealed in a jar, were dusty, and Joanne cleaned some with soap and warm water. See our grouping in the photograph above; we had to bag the different types of marbles for conservation.

Say What?

Of course, we were dealing with devitrification of the glass marbles and not dust. However, we could not even identify the glass marbles at first. “Devitrified glass has a frosty or cloudy, iridescent appearance.” [Hamilton, page 2 of 3]. We were surprised when soap and warm water generally cleaned the glass nicely. Joanne was the first to say that what we had was not dug or found marbles, but marbles from an underwater site. Shipwreck marbles.

We had seen what we thought were non-fossilized crinoid stems (see photo above) in the group as well as non-fossilized bits of brain and stem coral and one other sea creature which we could not identify. At first, we thought finding sea creatures in the old jar a bit odd. Having no background on the marbles left us in the dark, but once Joanne put two and two together, it did make perfect sense.

Our first thoughts were that we were looking at German shipwreck marbles. However, as we looked at the lot laid out on the tray it became obvious that there was not nearly enough “bling” for a German find. We would, for example, expect to see Clambroth, Peppermint Swirls, Lutz ribbon cores, lobed handmades, and external ribbons of all types. We saw none of that.

Principally, we saw stone, earthenware, clay, Bennington and Bristol glaze, decorated stone, and a few glass marbles. It took a great deal of reading and study before we slowly realized that these marbles are most likely Dutch. “It is believed by some that the first major production of handmade glass marbles took place in the Netherlands before the Thuringen region [in Germany; italics added] began production.” (‘Refiner of Gold’ 3/31/2014)]. The Refiner of Gold is a valuable resource of information on all types of marbles.

Glass Marbles

The glass marbles lend credence to our theory about a shipwreck. We only have nine (9) glass marbles. Only one is “cane cut.” A cane is “a glass rod from which handmade marbles are fashioned. The rod is typically constructed layer upon layer of clear and contrasting colors. “[8] Again we reference our post about German glass house marbles: The Lauschaer Glashütte and the Origins of Modern Glass Marbles

Marbelschere or marble scissors were not used on this 11/16” marble. It was simply twisted from the punty and the resultant stretch marks and external pontil were not ground down. It is a simple transparent complex core swirl of blue and pink which are not lobed. We believe the marble is Dutch and that it probably dates to the late 1830s – early 1840s.

This cane marble has less devitrication than the rest. The rest of the glass marbles are, with one possible exception, handmade and hand gathered swirls. Some of the pontils appear sheared rather than ground. We have cobalt blue, green, purple, amber, brown, red, and green. Size ranges from 13/16” for the green to 9/16” for the blue, which is broken almost half in two. One marble is so dark that it looks like an Indian but it is not. None of the marbles are perfectly round.

And none of these marbles could be considered opaque. Leaching and devitrication has changed the composition, at least on the surface, but they were translucent at one time.

Finally, we have one glass marble which is a Banded Opaque Swirl. “These are made of opaque glass with wide bands that usually swirl from the top to the bottom. These bands are sometimes all of one color but often are of different colors.”[9] The marble only has three bands left, there is some built-up salt-base corrosive on one pole, and on one side the banded glass is leached away leaving the white opaque base which at first looks like chalk. However, on closer examination it is obvious that the base glass is stable (non crystallized). While there is a pontil on one pole we cannot tell anything important about it.

So, it was both the absence of glass and the nature of what we do have that led us, after much discussion with marble experts and collectors, and research, to believe that our entire lot is Dutch and that it dates to ca. 1830 – 1840. (See image above.)

Glazed and Slipped: Tin Glazed Dutch Delft

We have seven (7) white glazed marbles. They are ⅞”; ¾”; two 19/32”: and three ½”. One of the ½” marbles is badly stained with ferrous oxide rust transfer which is almost in a circular pattern. This stain certainly did not come from the jar.

Again, after much study, of Bristol and other slips, we decided that the glaze is Dutch Delft. The earliest tin-glazed pottery in the Netherlands was made in Antwerp by Guido da Savino in 1512.

The use of marl, a type of clay rich in calcium compounds, allowed Dutch potters to refine their technique and to produce much finer ceramics.

Delftware was a blend of three natural clays, one local, one from Tournai and one from the Rhineland.

From about 1615, the Dutch potters began to coat their pots completely in white tin glaze instead of covering only any painted surface and coating the rest with clear glaze.

They then began to cover the tin-glaze with clear glaze, which gave depth to the fired surface and smoothness to cobalt blues, ultimately creating a very good resemblance to Chinese porcelain.[10]

We also have one ½” blue Tin Glazed Dutch Delft. It has ferrous oxide rust transfer from something it lay against; perhaps nails from the crate in which it was stored. Generally, marbles were crated in the hold of the ship for transport.

We think that it was natural for the Dutch to use a glaze on marbles which they had used for many years as an underglaze on their tablewares and other pottery.

Rockingham-type Glaze

We have four brown glazed marbles which at first give the appearance of Bennington. Unfortunately, some marble collectors refer to all brown glazed marbles as Bennington.

However, each of these marbles has one, and not two eyes, and one glaze is almost yellow instead of brown. Another is almost black. One marble is what, one hundred years later, in glass marble production, is called a football. 23/32” around, it is 1” long! Certainly, a child could play with it, because it does roll. This oddity did not happen on the seafloor, but in the pottery.

The yellowish marble is 13/16”; another <>23/32”; and the darkest brown is ⅝”. A pottery in Swinton, near Rotherham, West Riding, Yorkshire, England,[12] was experimenting with Rockingham glaze as early as 1745 and it finally closed in 1842. Rockingham glaze was imitated by many potteries in Europe, and made its way to America where it was used on utilitarian ware by many potteries including the ones in Bennington, Vermont.

Mid-fired white-Bodied Clay

We have seventy-seven (77) dyed clay marbles. They were fired. The clay is white to tan and has been fired to such a high degree of heat that the marbles became almost porcelain. We used a metal hammer to break one and both of us saw sparks fly when the marble broke because it was so hard! We kept the five shards of marble with the sublot.

Size ranges from ⅞” to 15/32”. The marbles are in generally good condition but they do have holes and gouges. Some have lost almost all their color, but others remain bright. Colors include: yellow; tan; green; blue; red; and purple.

While unglazed pottery has been recovered from shipwrecks which are thousands of years old, we knew that common earthenware marbles are very porous and might have dissolved. This led us to break one marble and we realize now that these marbles would probably never dissolve. We have never before seen dyed clay fired to such a temperature.

We began to think again about the Delf glaze . . .

. . . both blue and white on some marbles and slowly came to the mutual conclusion that what appear to be common dyed earthenware marbles like those pictured to the left or the Allbrights pictured in Grist on page 36 are in fact not.

They are Delf; a mid-fire stoneware clay body fired first at between 11600 Celsius (21500 F) and 12250 Celcius (22600 F). After the glaze is applied they were fired again at a temperature of 12000 Celsius (21920 F).[13]

These marbles are made of the same material as the Delft ware being produced ca. 1840. While the number of potteries had certainly declined and the decoration could not match their earlier work, the fundamental techniques of production had not changed significantly.

Potters Using Clay

It is interesting that in the United States we have found many cases where the potters used whatever type clay was being used in production of jugs and other utilitarian wares to also produce marbles. Generally, these marbles were a sideline and not a production item – eg at a fire resistant brick plant in Tennessee; using local clay in Pensacola, Florida; and in Jugtown, Georgia. To read a comprehensive study on this practice see Chapter Three, “Schlepping off to Jugtown”, in our book The Secret Life of Marbles .

Still, the final product of the Dutch so resembles an ordinary common earthenware dyed, shellacked, or painted marble that we can only imagine that almost all collectors who did not know their history would pass them up. In our case, the attribution for the marbles comes most directly with their association in an antique sealed glass jar with other shipwreck marbles and detritus.

Finally, we have one <> ⅞” blue marble with an applied slip which appears to be spatter ware. However, this technique was not used as early as the 1840s. The color is not applied evenly but in streaks and spots, and it is nearly cobalt in color. The marble is made of the same mid-fired stoneware and the unusual color application may have been intentional, the result of poor firing (or the failure to second fire-apply), or degradation over time.

Unglazed & Natural Clays

We have fourteen (14) clays which appear to be unglazed or which were slipped in a natural tan color. They range in size from ⅞” to 15/32”. The larger marbles are white kaolin fired at mid-range. On first examination they look like British chalk marbles, but close examination proves this observation wrong.

The 15/32” marble is hand formed and it does have inclusions although Ferris oxide does not appear to be one of them. It looks like terracotta. While we know that the Dutch were creative tile makers, we thought their tiles were Delft (tin glazed). We have no idea how this marble got into the lot nor any idea how large it may have been before it degraded.

Overall the marbles are in good condition. Doubtless some were originally dyed. One has two raspberry colored dots of color; another has a bit of blue. This blue one, which is ⅝”, has a hole in it which appears to have been bored. It is not very deep and we have no idea why it is there. Others have impurities, ferrous oxide staining, and what in glass production are called blow-out holes. Doubtless these were caused by salt water degradation over a long time.

Undecorated Stone

We have fifty-three (53) undecorated stone marbles. We have two 1” and one ⅞” while the smallest is 7/16”. Many of the stones are stained and some have a heavy accumulation of Ferris oxide stain in circular patterns.

“Limestone marbles are among the oldest marbles made from stone and date to no later than around 1575. The earliest limestone marbles were from the Berchtesgaden-Salzburg region of Germany and are often recovered from archaeological sites in Amsterdam.”[14]

Some of the marbles are remarkably smooth and the larger ones were well-polished. On the other hand all are planar and it is obvious that they were fashioned in the manner explained by Marble Alan and in the excellent illustrated essay “Limestone” in Baumann pages 16 -18. His entire Chapter “Stone Marbles” pages 15 – 21 is first-rate.

Some of our stone is limestone and some is not. One or two are deeply gouged and another couple have pits all over the marble. In fact in the shop we thought one pitted one was Native American and finished with an antler tine.

Finally, it is possible that there are one or two stoneware marbles in this sublot which once had white (possibly tin) slip or glaze. If so, the glaze is worn so badly that it is almost impossible to tell undecorated stone from stoneware.

Decorated

We have twenty-one (21) decorated stone marbles. “Some limestone marbles were dyed, and though it is not known exactly when this first took place, such dying was conducted at least by the 1880s. Most of these dyes were in shades of blue and red. Some naturally yellow limestone marbles with brown banding have been found.”[15]

In fact, most of our decoration is in the form of a single helix in blue or black. The marbles range in size from ⅞” to 17/32”. One 13/16” limestone marble has an indistinct flower on one pole. This marble also has an odd circle, which appears to be stamped, on one hemisphere and beside this a distinct ‘5’ which appears to have been stamped into the stone. A light-colored ⅝” marble has an ‘A’ scratched into the side. One ¾” has a ‘13’ scratched into one side while one ½” has what we can only decide is a windmill. If not that then a wasp, which makes no sense at all.

These marbles are in good condition, although the decorations are faded. There is alsoferrous oxide staining on some and a darker stain on others. Again, it is possible that one or two stoneware marbles with white but badly degraded glaze could be in this sublot.

Dutch Ceramic Donut Beads

In Justin’s shop and even at home we thought these beads were non-fossilized crinoids stems. Joanne cleaned them and only then did we realize that some had Rockingham-type glaze, some had a Delft white to light green, and some were unglazed. There is one single “bead” which looks like a bead spacer.

Larry gained ceramic and glass bead experience when he volunteered for five and a half years at the archaeology lab at the University of West Florida. We both gained experience while volunteering at the Osceola Historical Society in Kissimmee, Florida, for a number of years.

We researched Dutch beads online and learned that the Netherlands were major producers and exporters of beads to North America between ca. 1554 – 1730, and we know that, like Delft itself, bead production continued long after this. The Dutch were major suppliers to the Native American tribes such as the Iroquois, who in turn traded beads widely, and to the Susquehannock.

What Type of Bead?

We had no idea what type bead we had but thought at first that they were glass annular ring or wound trade beads. Some of the “stacks” are broken in such a way that we can see inside the material, and we realized that they are ceramic and that some are glazed. Bead size varies. Still, the stacking puzzled us.

Finally, we decided that these are in fact Dutch Donut beads and that they were strung before and to facilitate shipment. Evidently it was much easier to keep track of thousands of tiny beads when they were strung together than should they be poured into a crate singularly.

Now we were left with the question: how did they get fused? Most “stacks” had filled with sediment and we could not see a clear hole through them.

Trade Beads

On 1 April 2014 Larry called the supervisor of the archaeology lab at the University of West Florida. She said that she and the University archaeology students had found thousands of trade beads over the years. She said they were made of glass, ceramic, silver, and other metals.

As to our fusion, she said that one of two things probably happened. First, she said since some are glazed then the mid-range firing needed to bond the glaze to the body would have fused the “stack”. In effect, Joanne noted, this would have created one long bead made up of a half dozen or more smaller beads.

She noted that the other possibility is that there was a fire aboard the ship. In light of this observation we checked our entire lot again and noted that many of the marbles, especially stone, do have dark staining which could be from smoke/heat. This is noted in the descriptions above. And, of course, we have no idea how or why the ship sank.

To be precise, the archaeology supervisor was working from years of study and experience in the field and the lab and she did not examine the beads. And while Larry is less certain of these beads than anything else in the shipwreck lot, in Joanne’s professional opinion they are beads as described so we will leave it at that.

Coral

Finally, we have five (5) pieces of brain and stem (branch) coral and one pebble. We wish these pieces of coral could help us pin down where the wreck occurred, but they don’t. Brain coral can grow for centuries like an old oak tree, and it is found in the Caribbean, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans. The largest we ever found was in the Gulf of Oman. Branch coral is also grows all over the world. We have no idea type branch coral we have; it would be nice to know if it is a type of reef coral.

We are left with many questions about the assemblage. When was it recovered? The jar probably dates to the late 1800s. Rubber jar seals have been used since at least 1900. And generally people would buy new rubber seals to use on older fill jars. We did not look for a maker’s mark since Justin kept the broken pieces. So we don’t know whether or not the jar was made in America.

Scuba Diving?

Did someone recover the marbles while scuba diving? Free diving in deeper water? As part of a larger dive project searching, for example, for treasure? Once ashore how did they find their way into the jar? The glass jar is certainly not from a museum. And why place all these things in a fill jar, seal it, and stash it away without ever studying and enjoying it further?

We wish we knew the answers to at least these questions. As we have said before provenience and provenance are important to any marble collection. Still, after innumerable hours of study, we are very happy to have saved this little assemblage and made some sense of it.

A Last Look

Over the years we have been told by visitors who enjoy seeing our shipwreck collections that there can be no ceramic (most people say “clay”) marbles from a shipwreck. They would melt under water, people claim. Well, to end our discussion of the ceramic, glass, and stone marbles we have reference just one recent Archaeological find.

An ancient Roman shipwreck was discovered off the coast of the Greek island of Kasos. It has been dated to between 200 and 300 AD and it was loaded with cargo to include intact ceramic amphorae.[16] These are the “clay” containers with pointed bottoms. Our non-glass marbles, in light of these amphorae, and dozens of other under water finds which we could list, are relatively “new”.

What about our nine glass shipwreck marbles?

Won’t devitrification eventually “eat” the glass completely away? Well, devitrification is a geologic term; fundamentally the conversion of glass to crystal over time and in specific environmental conditions. We are unsure how “deep” on the glass surface the process could convert the glass if the marbles are left on the seafloor for many centuries. However, you should check our book, Chapter Eight, “Shanghai Stinkers,” of our book The Secret Life of Marbles

In this Chapter we discuss the Sinan shipwreck off the coast of Korea. Glass marbles were among the 20,200 artifacts recovered and displayed in the National Korean Museum. These marbles were shipped from China in 1323. We have no idea how devitrified the marbles were or are, but remember this was some 650 years ago. So, again, our nine shipwreck marbles are almost brand new in comparison.

Conclusions

Shipwreck marbles are on the market. While not rare, they are hard to find. And they may be found in unexpected places: coin shops; dusty flea markets; and with brokers who have bought them in estate sales. Sometimes pickers who know nothing about marbles or shipwrecks will find an odd lot here and there and then sell them at flea markets.

Be cautious, however, of “sea glass” marbles. What is the difference in geologic divitrification of glass and a light acid wash? Can you tell the difference just by looking at a marble? Beach marbles can be found and sometimes in surprising numbers; we know where they are common. But we have looked on beaches all over the world for glass marbles and we have never found one!

Provenience and provenance are important. Before you buy listen to the owner’s story if she or he has one. It may sound fantastical, but there may be kernels of truth in the story which you can pull together with research, study, and consultation with professionals in the field. The back story is critical. But just because the lot does not have one does not automatically mean that the lot is worthless. And, finally, try to buy and trade with people you know and trust. People you have a history with.

Felix venatio!

Want to read more about shipwreck marbles?

Notes

- “Artifact Conservation” San Diego Natural History Museum. https://www.sdnhm.org/exhibitions/titanic-the-artifact-exhibition/artifact-conservation/ (6/15/2022); “Marbles From Shipwrecks” November 2012 MarbleCollecting.com Newsletter http://www.marblecollecting.com 6/15/2022 ↑

- Davies, Peter, and Adrienne Ellis. “The archaeology of childhood: toys from Henry’s Mill.” The Artefact 2005, 28, pages 15-22 and Lawrence, Susan, and Peter Davies. An Archaeology of Australia Since 1788. NY: Springer, 2011,page 197. ↑

- Reference: https://phys.org/news/2020-09-devitrification-demystified.html 6/19/2022 ↑

- For more information see “Micas” @ Old Rare Marbles https://oldraremarbles.com/product-category/mica/ 6/20/2022 ↑

- We have his name in our files. ↑

- We have his name in our files. ↑

- We used all of the resources we could to identify them: Grist; Antique and Collectible Marbles, 3rd Ed.; Stanley A. Block; Marble Collectors Society of America; Hamilton, Donny L. “Methods of Conserving Archaeological Material from Underwater Sites.” 2000. Conservation Research Laboratory, Texas A&M University, Nautical Archaeology Program. http://nautarch.tamu.edu/CRL/conservationmanual/File5.htm/ (4/1/2014); Telephone consultation with Burt Wilkins, marbles expert, appraiser, who buys and sells antique and vintage marbles. 4324 Lake Underhill Road, Orlando, FL. 31 March 2014.; Telephone consultation with the Supervisor, Archaeology Laboratory, University of West Florida, Pennsacola, FL 1 April 2014. Larry volunteered in the Archaeology Lab under Lloyd’s primary supervision for 5½ years to include five summer field schools in the Escambia County, Florida, area. We have her name in our files. ; http://refinerofgold.com/marbles/ (‘Refiner of Gold’; “Handmade Glass Marbles” 3/31/2014); and Baumann. http://www.antique-marks.com/tin-glaze-ceramics.html 4/3/2014 ↑

- [Parr in Block, Stanley A., Ed. Marble Mania® Revised & Expanded 2nd Edition. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2010, page 229; and http://imarbles.com/kindsofmarbles.php 2 April 2014 ↑

- Grist, page 24 ↑

- “The History of Tin Glazed Pottery Ceramics. The manufacture and examples.” http://www.antique-marks.com/tin-glaze-ceramics.html 4/3/2014 ↑

- Dutch tin glazed wall tile: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O162833/wall-tile-unknown/ 6/22/2022 ↑

- “Rockingham ware”. https://www.britannica.com/art/Rockingham-ware 6/20/2022

- See http://souvenirsfromholland.com/ 6/21/2022 ↑

- https://buymarbles.com/marblealanhome.html (Marble Alan) 6/21/2022 ↑

- Marble Alan ↑

- Cascone, Sarah. “Marine Archaeologists Have Uncovered an Ancient Shipwreck Filled With Treasures Off the Coast of Greece.” 27 January 2021. See: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ancient-treasures-recovered-from-shipwreck-1939671 6/23/2022 ↑