Guest Author: Caroline Janssen

[Editor’s Note: Here we introduce you to Caroline Janssen and her thoughtful analysis of a book, the human spirit, and the role of marbles in society. Caroline is a professor at Ghent University (Belgium). She has previously contributed to this magazine with her article about the history of marbles in the nation of Kuwait.]

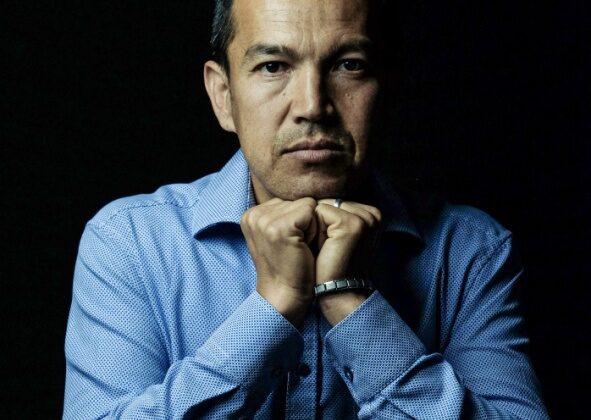

Qadir’s Marbles is based on the life of Qadir Nadery (photo above). He is a man from Afghanistan, a father, who, through the vicissitudes of life, saw his status turned into ‘refugee.’ His ethnicity and activities made fleeing his country the only viable option. He belongs to the Hazara, an ethnic group of mixed Mongolian, Iranian and Turkmen ancestry, who look different from the dominant Pashtun population. Most Hazara are Shiite Muslims, and tolerant toward other religions, and this, together with their ethnicity, leads to discrimination and violent attacks by the Sunnite Taliban.[1] Those who read Khaled Hosseini’s ‘The Kite Runner’ (2003) may remember the Hazara boy Hassan, who was raped by Pashtun boys and betrayed by his friend who looked down on him. Throughout Qadir’s Marbles too, we see instances of intimidation and brutality against this population. In addition, Qadir worked for international troops in Kabul and when the Taliban found out, he and his family became targets.

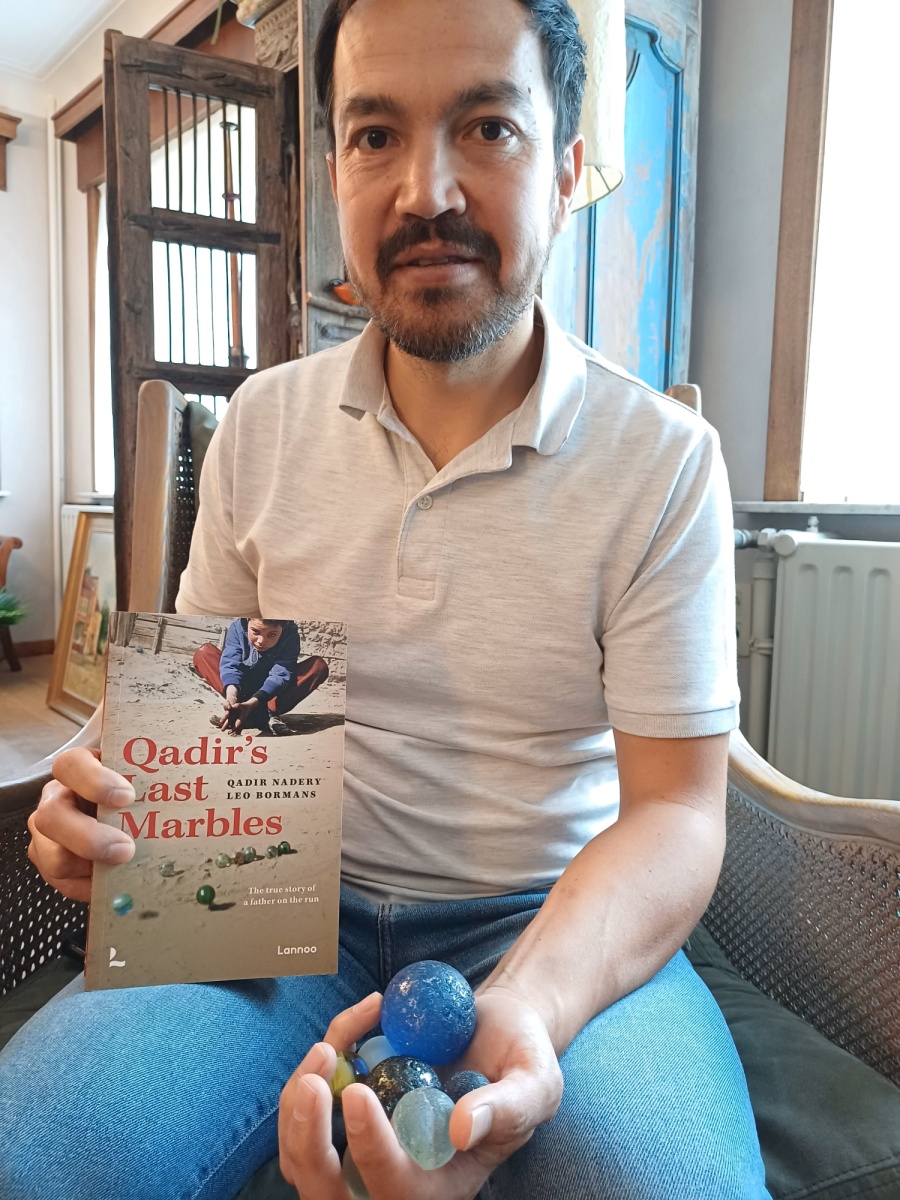

Having escaped nightmarish conditions in his home country Afghanistan, he sought asylum in Belgium, for himself, his wife and his daughters, after a long and dangerous journey. Refugees who manage to reach safe territories are only halfway down the road. Many spend years in limbo with their families, not knowing whether they will be granted asylum or not. In this ‘in-between life’, these years of insecurity, making friends can make all the difference. A chance meeting with Leo Bormans, a Belgian author who writes books about happiness,[2] turned out to be life changing for Qadir Nadery. They became friends and Qadir shared his life story with him. Then one thing led to the other. They sat together numerous nights; in close collaboration they turned his experiences into a novel, a piece of fiction based on true events.

I must admit that the book caught my attention because of its title Qadir’s Marbles.[3] After the wonderful exchanges I had earlier, with Larry, Jo and Wendy, I proposed to write an article about marbles in literature. I got fascinated by the fact that marbles apparently mean so much to people in different parts of the world, much more than any other childhood toy it seems; that this ancient game, once played with nuts and stones, became the embodiment of family memory and childhood bless, as we saw in the case of the bank note from Kuwait.

One Story, Many Meanings

Objects in literature can be invested with all kinds of meaning, literal but also symbolic and metaphorical ones; they can have a function in the narrative structure of the book and be a focal point through which complex realities are evoked or stories are unfolded. Novels can thus shed light on the sentiments they evoke. In the book Qadir’s Marbles, a collection of eight marbles together with a pomegranate orchard epitomize the longing for a place called home. The marbles, like the author himself, are on the run, while the pomegranate orchard is his father’s dream, a vision linking to ancestral territories. The ultimate dream of a peaceful Afghanistan is envisioned by combining a large pomegranate orchard with children blissfully playing marbles in it. But in the book, the marbles end up buried, in a small allotment in Flanders, at some 3400 miles from home, and the garden remains an unfulfilled dream for the time being.

A novel like this is not an ethnographic study and one can wonder whether some elements are authentic or whether they sprout from fantasy. E.g., in the novel all the marbles are made of precious stones. For most readers it will not matter whether this is reality or fiction, but because you are interested in marbles and marble play, I decided to contact the authors who were as kind as to answer my questions with care. The e-mails I exchanged told me that the real Qadir Nadery is as passionate about marble play as the main character in the book. He remembers the games of his childhood in great detail. Returning to the materials in which the marbles are made, I can say that he shared that village children in Wardak, where the novel is set, a mountainous region at some 100 kilometers from Kabul, play with stone and glass marbles alike. Some are lucky to get hold of marbles made of marble or even lapis lazuli, which is not expensive because the stone is found in the region. So, although the precious marbles in the book are an adaptation of reality, it is not unthinkable that the boy would have such marbles.

Gemstones and life stages

The book Qadir’s Marbles consists of a prologue, four chapters and an afterword about the war in Afghanistan. The four main chapters are named after gemstones that belong to the natural treasures of Afghanistan. They are called Topaz, Emerald, Jasper, and Ruby. They represent successive phases in the author’s life. Each of the stones is believed to have a secret force that protects human life; or so it is ‘whispered.’ The secrecy can be attributed to the fact that although it is a widespread belief, in Central Asia’s Buddhist and Islamic cultures (and far beyond), attributing healing powers to stones is forbidden (haram) according to fundamentalist Muslims who view it as idolatry.[4]

In the novel, objects made of natural materials and human beings are interconnected on a spiritual level, which is how people living close to nature often feel; although one can interpret such connections as metaphorical, this perception is not uninteresting from a contemporary ecocritical perspective which tries to overcome the western-style dichotomy between humans and their environment. E.g., Qadir’s grandfather is said to have told him to live healthily because our bodies are full of gemstones and precious metals, gifts of the earth.

“Your kidneys are your emerald, your lungs are silver, your stomach is gold and your heart a diamond. A healthy man looks for treasures under the ground and in mountains. Only when he falls ill, he discovers the real gems in his body. But then it is too late.”

Now we understand why the marbles in the novel all are made of precious stones. They have secret powers which reinforce the boy. Qadir’s favorite marble is said to ‘glow’ in his hands in scenes of high emotivity. A whole series of emotions, including a sense of destiny when the author meets his wife-to-be, are expressed in terms of marbles.

Beginnings

Chronologically, it all starts with a collection of twenty marbles, shared by two little friends, Qadir and Ayob, who live in a remote mountain village in Afghanistan. At that point, the marbles lead an uneventful and rather predictable life, if they had their secret histories before they ended up in these boys’ pockets, we would not know. Little did these friends anticipate that later in life, both Qadir and eight of these marbles would cross the Mediterranean.

The childhood scene is not the beginning of the book. The prologue or opening scene is focused on a pivotal point in the main character’s life: he is about to board a rubber boat across the Mediterranean together with his wife Salima and their two daughters Soraya and Nargis. By then, the couple had lost and buried their infant son who had sadly died en route from an asthma attack in the dust of Afghanistan. While we may associate the Mediterranean with idyllic Greek islands and marvelous shades of blue, during the refugee crisis it has also become a grave to many hopeful / desperate migrants crossing it from places like Turkey or Libya. We are reminded of Homer’s verses about the wine-faced sea, a treacherous place where storms rage and people drown. Refugees are aware of the dangers but still take the risk. The Somali-British poet Warsan Shire (1988-) expressed it eloquently in her poem ‘Home’: ‘No one leaves home / unless home is the mouth of a shark; and ‘no one would choose to put their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.’[5] We first hear about the marbles when the smugglers strip Qadir of his last valuables:

“The cashier asked for more money. He looked at our wedding rings and the ruby earrings I had given to Salima as a wedding gift. (…) I decided to give up my wedding ring. No one would touch the ring and the earrings that I had given to Salima as a wedding present. And the eight marbles in my backpack were of value to no one but me.”

The marbles are the only material link between the refugee and his former self. They are no longer his toys but ‘linking objects’,[6] which have a value only he can grasp. One can compare them to an embroidered handkerchief, medallion or hairpin once belonging to a beloved deceased grandmother.

Topaz (1989-1999)

The power of topaz is that it makes people invisible to those who wish them harm. Invisibility is a primary concern in a land torn by civil war. Keeping low profile is how Hazara survive, breaking with this unwritten code could mean a swift death.

The section ‘Topaz’ covers Qadir’s childhood. In the opening scene of this chapter, little Qadir and his friend Ayob are playing a marble game called ‘bombardment.’ Ayob’s marbles lie in a small circle and if Qadir can hit one with his eyes closed he can have it:

“Baf! From eye level, eyes closed, I drop my largest marble with a dull thud. I did not hit a thing. Ayob’s father looks at my father, shaking his head, then he goes on with his work. The rules of the small war that we play he does not understand. The rules of the big war in his head are unknown to us.”

The boys, in this stage of their life, live in a parallel world. The word ‘bombardment’ creates a link between the boys’ and their fathers’ respective realities. What is more, in this scene Qadir suspects that Ayob is peeping through his eyelashes and cheating. This foreshadows the development of his character later in the book; Ayob becomes a middleman in an international network of human smugglers.

The ‘bombardment’ game exists in Afghanistan; it is called ‘danda klak’ as Qadir Nadery explained to me. The marbles are put in a row and a circle is drawn around them in the sand. One by one, the players ‘shoot’ a marble down, trying to hit the other marbles, like in a bombardment. The marbles that end up outside the circle are collected by the shooter. It is normally not played with closed eyes. Although kids playing silly could potentially do anything they like, this detail is only there to weave the narrative and create cross-connections in the story-line. The authors shared with me that this was a fantasy; that in reality, playing marbles is about focus and technique, not about making accidental hits. But then of course creative writing is about imagination.

The value of marbles – the only toys these village children have – is also explored in the book. They are a status symbol; whoever has more than three gains the respect of others:

“With twelve marbles I feel like a prince, ringing rich. Together Ayob and I have twenty of them. We count them every day, as if they were worth their weight in gold.

Echoes from the Shahnameh: Rostam and His Horse

In the child’s fantasies, his marbles do not only have hidden forces; they merge with the heroes of his mother’s bedtime stories. Her narrations draw on oral traditions that are interwoven with Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, an Iranian epos comparable to Homer’s Iliad or Odyssey. Written around the year 1000, the Shahnameh is still highly popular among in Central Asia and motifs and verses from it are used to give strength to the youth and shape their morals.[7] One of the most famous episodes is that of the hero Rostam and his horse Rakhsh. In the boy’s mind, they are (like) him and his favorite marble:

“Songha is the biggest one. He is the boss of all the marbles. Songha and I are invincible, like Rostam-With-The-Tiger-Skin and Rakhsh, his Black-eyed Horse. At night, my mom tells colorful stories about them. How Rostam, the king’s youngest son, captures the magic foal with a lasso and how together they pass the Seven Trials to save the country. How they beat the Dragon of the Mountains with four blows, and then drench themselves in dragon blood because it grants them an everlasting force. My Songha has the red and golden colors of saffron leaves and the speckled skin of Rakhsh.”

The secret life of these marbles is something Qadir only shares with Ayob. Together they play out scenarios with monsters, snakes, dragons and demons that are defeated by their marbles.

Reality Hits

A dramatic event shatters their dreamy world. While working in the field, Ayob’s father is killed and Qadir’s father wounded by a blind missile attack. While his mother takes him in her arms, Qadir gropes in his pockets and realizes that he had lost five marbles while running to his father. His favorite marble Songha gives him the strength to control his fears. Its speckles remind him of those of the horse Rakhsh, which lit up when a lion approached Rostam in his sleep, thus averting disaster. Together with Ayob he starts looking for the lost marbles and it is Ayob who finds them. One is described as topaz blue, a second yellow like jasper and a third one is said to be ruby red (the description of these three marbles coincides with the titles of the sections of the book). It is a time of symbols and gestures, and the momentum is depicted in terms of marbles. Qadir generously lets Ayob keep the five marbles; together they still own twenty and that is all that matters. In turn, Ayob sneaks into his house, where mourners have assembled, and when he returns, he asks his friend to open his hand:

“Don’t look”, he says. I feel how he places a marble in my hand and then folds it. When I open my eyes and my hand, I see the Sardonyx, his favorite marble.”

Twelve minus five plus one is eight. Eight are the marbles that stay with Qadir. By then these marbles are already so much more than toys; they now symbolize the bond between the boys.

Playing marbles is something boys do in the streets. Their favorite game is another marble game called tushla baazi. At school, they cannot play it for fear that their teacher – on days the teacher is there– will administer harsh corporal punishments. Instead, during his absence, the children play with stones or little sticks, or they play tag. They draw circles in the sand but cover their traces afterwards. Playing tushla baazi at home is also a no-go for Qadir. Qadir’s father frowns upon him playing marbles out of fear that the game would turn his child into a reckless player or gambler. Sometimes Ayob and Qadir play against other children in the streets. The fact that it is almost a forbidden game makes it all the more exciting.

The authors describe the game in detail:

“Ayob draws a circle in the sand. Taking turns, we throw from ten meters distance a marble in the direction of the circle. Mine comes closest, so I may begin. Ayob has bad luck. His marble has landed in the circle so he cannot play this round. (…) I feel strong. My master marble Songha I never bring out, but I feel it glow in my pocket, where it warms my blood all the way up to my fingertips. Every shot hits the mark. Even when the other play the Elephant’s Game and start stamping hard on the ground, to take my marble off course. They do not know that Rostam could even cope with a thousand elephants!

I win two marbles. Ayob catches up and wins three. On our way home we feel as invincible as Rostam and Olad on their journey (…). Ayob has cheated. I did not say anything about it but he knows that I have seen it.”

As they grow up, the boys grow apart. Ayob starts hanging out with the wrong crowd. Qadir starts working in a garage, at two hours from home. His first job comes to an abrupt end when a suicide terrorist blows himself up at his workplace, wounding his boss, killing a friend. The region becomes more and more dangerous. A plan to go and buy lapis lazuli marbles with another friend – blue marbles will grant luck in the game – is aborted when they are forced by bearded men in a jeep to witness a public stoning of two young village girls. The young Qadir becomes increasingly aware of the big war and feels powerless:

“I do not know whether I want to become a man. I want to play. Not because of the marbles but because of the game. But I wonder of which game the light blue corpses and the thousand men and boys in the mass graves are a part. Maybe I just imagined the glow of Songha, and maybe the heroes of my childhood are for always defeated. I am twelve years old and feel confused and lost between the game and the marbles.”

Emerald (2006-2014)

“In the deepest green of the emerald, it is whispered, spring is glittering.” The royal stone allows one to see growth and pain simultaneously, find life in a grain of sand. Its force is immortality. The emerald period starts at the brink of adulthood and ends with the author’s decision to leave Afghanistan.

The main character, at 25, reevaluates his life and decides to leave the village. Through a friend he finds a job in Kabul in the cultural section of the French embassy; foreign services hire Hazara people from the countryside, because they have no links with terrorist organizations. In Kabul the author becomes aware of extremes: rich people literally swim in their money and own rooftop pools, while others clad in rags, missing limbs, roam through the streets, victims of attacks that, as the book expresses it, ‘are rolling through the streets like deadly marbles.’ It is a gloomy metaphor. The marbles also appear in a macabre setting in the description of a piece of conceptual art that is said to have been created by an Afghan and a French artist and to have been at display in Kabul’s French cultural center. Red paint ran through a tower of bottomless bottles. The bottles had dates written on them; the artwork represented “the endless downward spiral of bloodshed” in Afghan history. The construction was set into motion with the aid of colorful marbles rolling through the bottles, ending in a pool of blood red paint littered with glass shards. The author somehow feels that the artwork represents his own life, that jasper and ruby marbles run through it until they end in a pool of blood. Sometimes works of art have the power to predict the future, the book says. The French Cultural Center was blown up in 2014 by a teen suicide bomber during a theater play. More than 15 people died in the attack, many were wounded, and the place was ravaged:

“We are shocked. We sit and watch. It seems that we will never play football again or play marbles in a courtyard, as if every dove of peace is being shot down before she can leave her nest, as if heaven touches hell.”

Playing marbles here means innocence, a life free of the ugliness of war. When a close colleague is murdered, this man’s grieving father tells Qadir to leave Afghanistan and for the first time Qadir considers doing it. This becomes a now or never when Qadir learns that the Taliban got a bead on him and his family. Again, I am reminded of Warsan Shire’s poem ‘Home’ where she states: ‘No one leaves home until home is a voice in your ear saying- leave, run, now.’

Jasper (2015)

Jasper protects the traveler and strengthens the will, even if the one carrying it is near the point of exhaustion. The travel over mountain trails, through Iran and Turkey, with two small daughters and a heart filled with grief, requires courage. The family must wait for two months in Iran before it is safe to continue. Their survival depends on the children’s capacity to be silent. They promise them ‘a big wedding party’ at the other end of the sea and buy pretty dresses to give them hope. Again we see how stories lend strength to people. When they finally arrive in Greece, the marbles are said to be tingling, ready to play a new game on a new soil. They are “the only tangible memento of the place where I was born,” Qadir explains. The other memento, a family photo, did not survive the sea water.

Ruby (2015-2020)

In ruby two deep-red streams flow together; pulsating love and endless bloodshed; it is a sparkling heart that lovingly gives new life created from coagulated blood. The author’s ordeal is not over, four years of uncertainty follow, where the family is at the mercy of immigration officers. In their new country they find a hundred friends who pay fifty cent a day so that they can rent a proper house and leave the asylum center. In the book, when they finally get the permission to permanently stay in Belgium, the marbles are ritually buried. They are invested with another layer of meaning. They now become the beloved dead that were left behind in Afghan soil: the author’s three siblings, the Hazara friend who was shot for celebrating new year in the mountains, friends who died during terrorist attacks, and last but not least, his little son;

“The eighth marble is the largest and most beautiful one. It shines like a ruby which brings together in its deepest red the confluence of two blood streams, the arteries of pulsating love and the swirl of never-ending bloodshed. Petrified silence of clotted blood. It is Songha who gets the name of our little son Khaibar, who died in my arms at the first sigh of our flight. He never became a champion marble player. But the memory of his smile on his face, the dimples in his cheeks, are stored, deep in my heart.”

It is obvious that this autobiographical novel is not for the faint of heart but when the English translation becomes available I can only recommend reading it. It is an insightful book, not in the least because it magnifies the voices of people who too often end up on the wrong side of statistics and are dehumanized or demonized on political battlegrounds. It exposes how the immigration officer who handled the case lost himself in detail but failed to grasp the social fabric, leading to interrogations best described as Kafkaesque. The book Qadir’s Marbles has been incorporated in a list of books which were selected by the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) as essential literature.

It is obvious that this autobiographical novel is not for the faint of heart but when the English translation becomes available I can only recommend reading it. It is an insightful book, not in the least because it magnifies the voices of people who too often end up on the wrong side of statistics and are dehumanized or demonized on political battlegrounds. It exposes how the immigration officer who handled the case lost himself in detail but failed to grasp the social fabric, leading to interrogations best described as Kafkaesque. The book Qadir’s Marbles has been incorporated in a list of books which were selected by the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) as essential literature.

For lovers of the marble game, it is on top of all this a literary tribute to this source of childhood bliss. It may inspire you to reflect on the role of marbles in your own life story.

About a Marble From Afghanistan

Songha somehow fascinated me and I looked for an Afghan marble in stone to illustrate this article. I stumbled upon an object described as an 18 mm marble ball from Afghanistan, from the first half of the first millennium AD, which was made of a highly polished coralline limestone.[8] This marble ball is speckled like Rakhsh, the horse, and is Qadir’s favorite marble. Like Qadir’s marbles it had once been buried. But it is not because the object is shaped like a marble and looks like a marble that we know its secret. But looking at its archaeological context can be helpful. In the first millennium, Afghanistan was a Buddhist country (think of the Buddhas of Bamiyan). So, this marble is part of an archaeological context and the location where it was found reveals that it was not a toy. It was found among relics in the middle of a stupa. I then remembered being told during a trip in Myanmar, that when spiritual masters are cremated, there is a stone in their ashes, which is not the case for lay people. The larger the stone, the more virtuous the monk. So it is possible that this marble/ball embodies Buddha and has served as a śarīra, a relic linked to the virtues of the Buddha. The marble ball was unearthed and ended up in the British Museum through James Lewis, a.k.a. Charles Masson who, having deserted the Bengal European Artillery Regiment in 1822, roamed for five years through India, Central Asia and the Middle East. He was hired by the British East India Company and went on archaeological explorations in Afghanistan. When his true identity was discovered instead of being punished he was recruited as a spy in Kabul.[9]

The interpretation of this marble ball is very different from that of Qadir’s marbles because it is connected to Buddhism, but what all these marbles have in common is that they embody the essence of people, the quintessence of the human soul. Sometimes one wonders where stories begin; how generations of humans are kindred spirits whose souls make similar vagaries while trying to make sense out of their lives and that of others.

References

- https://minorityrights.org/communities/hazaras/; for the dehumanization and fate of this people see a.o. https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/the-plight-of-hazaras-under-the-taliban-government/. ↑

- https://www.leobormans.be/. ↑

- The original title is ‘De knikkers van Qadir’, ‘Qadir’s Marbles.’ The English translation which will be available shortly bears the title ‘Qadir’s Last Marbles’. Being a philologist at heart, I think that this affects the interpretation to some extent, so I use the original title in this contribution.For those interested in more background and live images: the co-author Leo Bormans made a clip explaining the background of this book: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ap-Nfb2uVN8https://catalog.2seasagency.com/book/qadirs-last-marbles/The last chapter has been rewritten in the English version, so that it is less centered on the Belgian context:https://catalog.2seasagency.com/book/qadirs-last-marbles/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tvs_8JV8_eY ↑

- A variety of opinions can be found online, e.g. on https://islamqa.info/en/answers/192206/ruling-on-dealing-in-so-called-healing-crystals. ↑

- Warsan Shire was born in Kenya in 1988. Her parents were Somali refugees who moved to London when she was two years old. Through her poetry we hear different voices and see different perspectives from the refugee community. She was a young poet when she was contacted by Beyonce to contribute to her album Lemonade. The poem ‘Home’ first went viral online and was revised in 2022 for her bundle Bless the daughter raised by a voice in her head, London. She now lives in California. ↑

- While psychiatrists branded attachment to ‘linking objects’ as pathological behavior, D. Klass (1996), who worked on Japanese ancestor cults, describes them more empathetically as a human way of coping with grief (Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief, Washington). ↑

- An excellent introduction to the Shahnameh is Hamid Dabashi, 2019: The Shahnameh: the Persian Epic as World literature, New York. ↑

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-3698. ↑

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG12317. ↑