Book image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Note: This post was revised September 17th to include new photos and research. New material is at end.

You’re Looking for the Wrong War!

There is a long back story [1] to how we came to study marbles and marble gaming in the American Colonies and then on into the eventual Revolution. Chapter Seven in our book The Secret Life of Marbles…, “Louse Races and Ring Taw: Marbles in the Civil War,” is about Civil War Marbles. We have also published two stories about these marbles here in our eMagazine: How are Marbles & Civil War Prison Art Connected? and Marbles Used as Munitions in the American Civil War.

We have searched for stone or clay American Civil War marbles for well over a decade. We did find direct and unassailable evidence that at least some soldiers did play marbles in camp sometimes. We traveled all over the eastern United States searching for Civil War marbles.

We learned something along the way: genuine authentic Civil War marbles are very hard to find. They did exist. However, very few diggers told us that they ever found marbles alongside camp lead, tampions, dropped bullets, and so on. While we know that soldiers played with marbles, such digger evidence would go a long way toward cementing our understanding that soldiers did game with marbles in camp.

Well, while digging through both physical and digital ephemera about the Civil War, we were both surprised and amazed to learn that there are a lot of Revolutionary War marbles available! And, it appears, there are tons of them for sale online to include eBay! To top that off, you can get a certificate of authenticity to go along with the marbles![2]

Wow, Civil War marbles scarce as hen’s teeth, but Revolutionary War marbles by the pound!

Focus!

We were astounded when we surfed the web and found so many Revolutionary War marbles for sale! We had been researching the wrong War all along. We did not make a note nor attribution of the odd entry that we first read when we were still looking for Civil War marbles.

But that unusual entry said that the Continental soldiers played marbles with their lead shot! Buck and ball was common ammunition during the War.

When we started researching the American Revolution we remembered that now we have four Armies who may have contributed marbles to the cultural mix: the Continental Army, British Army, French Army, and the Hessian Army.[3] Could that be one of the reasons why so many marbles were lost and are now found?

A Long History

Soldiers in the Continental Army had a long history of marble games. They grew up with marbles; they were a part of their everyday life. Of course, many colonists were from Britain where marbles were a part of the fabric of daily life.

At the time mostly boys played marbles in France where “Nine Holes” was very popular.[4] And the German mercenaries in the British forces came from a country where marble play dates to the Roman occupation.

Nine Men’s Morris Game

While we focus our attention on types of ringer and taw, or marble shooting games, we would be remiss if we did not mention the ancient game Nine Men’s Morris or simply Mill. It is also called Morris, Morelles, Merelles, and Merels. Some researchers claim that versions of Mill are the oldest known game. The Romans played the game and it spread along their established trade routes.

In Colonial America “…it was played by soldiers during the revolutionary war and was also popular with children who played it with marbles by drawing the board on the ground.”[5] One of the main reasons that the game was so popular with Revolutionary War soldiers was that it was easy to carry; it could even be drawn on the ground when needed!

The soldiers could also sketch a version of the game on a cloth and fold it up in their haversack. They did play with marbles and musket balls, but they also played using broken twigs and rocks as tokens or game pieces.

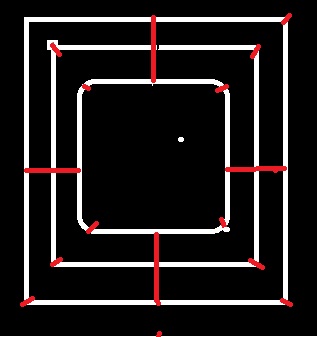

Just as there are many versions of the game, there are also many versions of the game board. This image illustrates a fundamental layout of the game. Colonial and Revolutionary players were so used to the game that they adjusted quickly to slightly different versions: or for that matter, playing in the dirt!

Used with permission of the Board President, The Depreciation Lands Museum, Allison Park, PA.

This Game Board Sure Looks Different

As you can see, “…the board is made up of three concentric squares and several transversals, making 24 points of intersection…. Two players, each provided with nine counters of a single colour, lay pieces alternately upon the points, the object being to get three in a row (a mill) upon any line [emphasis added].

On doing so, the player is entitled to remove from the board (capture) one adverse counter, but not one that is in a mill. Having placed all their counters, the players continue moving alternately, with the same object.

A mill may be opened by moving one piece off the line; returning the same piece to its original position counts as a new mill. The player who captures all but two of the adverse pieces wins. A move is normally from one point to the next in either direction along a line, but the rule is sometimes made that, when a player has only three pieces left, he may move them from any point to any point regardless of the lines.”[6]

“Knuckle Down to your Taw…”

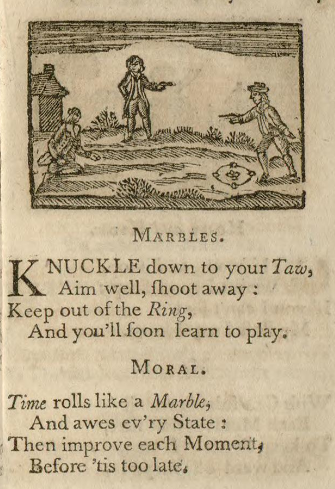

Now let’s look at Colonial ringer. This screenshot of page 27 from The Pretty Little Book was originally published in London by John Newberry in 1744 and this page is from the revised edition printed in Worcester, Massachusetts by Isaiah Thomas, and sold, wholesale and retail, at his bookstore, in 1787.

When this little book was first published in London, The War of Austrian Succession or King George’s War was underway (1744-1748). This War between France and England, as well as other Colonial Wars, did have a direct impact on the American colonists.

The American Revolution was fought from 1775 – 1783. By this time marbles, marble play, and marble games were embedded in America society and lifeways.

But war aside for the moment, we were fascinated that the words “knuckle down” and “taw” were in common use in marble play as early as 1744! Google the phrase “knuckle down” and you will learn that “Knuckle down” is a term derived from the game of marbles, it first appears in the mid-1860s in American English [emphasis added]. One puts a knuckle to the ground to assume the shooting position in marbles, thus the term knuckle down.”[7] Yes it did come from marble play, but it is more than one hundred years older than is commonly thought!

The word taw is even more obscure than knuckle down. Of course we know it as the marble you use to shoot in a game of marble ringer. Children used to have a very special taw: perhaps a California agate or another stone shooter. We have seen old glass taws simply worn completely down.

Etymologist agree that taw is of unknown origin, that it too relates to a game at marbles, and that it dates to as early as 1709.

Colonial Bowls & Plum

James W. Spain,[8] writing for the Concord Monitor, tells us this about Colonial marbles: “In 1720, one popular game of marbles was called bowling when the player would shoot the large marble from between the end of his forefinger and the knuckle of his thumb. The player aimed for the plum, another marble within a circle. When the player knocked his targeted marble out of the circle, he would claim ownership of his newly acquired prize.”

Colonial Bowls & Jack

We appreciate Spain’s contribution, but it does cloud the issue a bit. Believe it or not marbles were once made of pottery and they were nearly as large as a tennis ball! They were painted all sorts of bright colors.[9] And the game of marbles called “bowls and jack” was very popular in England. It is played very much like the game Spain describes.

However, in bowls the player rolls a taw toward a jack. While it has been a popular game for centuries across a number of countries, this game involves rolling a marble rather that shooting one.

And this leads us to carpet bowls. If you want to learn all about it then just check Section Two (beginning on page 144), “Carpet Bowls” by Roger Matile and Paul Baumann in Baumann’s Collecting Antique Marbles, 4th Edition. We have collected a few bowls and at least one jack over the years and if you haven’t explored this sister game to marbles, you might want to give it a look.

Players could bowl inside on the carpet or outside. Versions of bowls were very popular in pubs, and many of the bowls you find for sale today come from pubs.

Never on Sunday[10] Nor in the Graveyard!

Marbles were a fact of life throughout 18th Century America. As a rule boys and men played and, yes, men often turned the sport into gambling.

Since it was so common, marble gaming came to the attention of the local authorities and to the Church. The Corning Museum of Glass[11] tells us that “there was a time when playing marbles could get you in trouble with the law. In colonial New York, it was illegal to play marbles on Sundays. Several European towns in the 1500s passed laws that could fine anyone caught playing marbles in church or on church grounds.” And the same restrictions applied equally to schools.

We know that such regulations applied in the Southern Colonies as well and some forms of such prohibitions were still in place in the 21st Century American South. We have always found this odd because we have found marbles again and again at ancient lonely Churches all across the rural south as well as at old schoolhouses.

And we know of more than one graveyard where you can find marbles. These were not originally placed on a child’s grave. We have no idea why, but it’s true that some kids did find the smooth sand on a grave perfect for a game of ringer!

We even know of one untended graveyard where a worn path cuts directly across graves and where locals like to go to sit and talk and to visit with others in the evenings.

18th Century Toys and Game

We found this toys and games list on a National Park Service website; it was composed by Ruth Hodges and appeared in Liberty Minute Men, 2018. Marbles are listed as the number one toy in Colonial America! Of course, tea sets are on the list along with cards (whist was very popular), spinning tops, nine pins (a bowling game), knuckle bones, and toy soldiers.

Fishing, swimming, horseback riding, and ice skating were also popular Colonial games and sports. And, people love to gather to listen to someone read the newspaper.

The photographs of stone and clay marbles in this post are neither Colonial nor Revolutionary War marbles. In fact, the gray marbles clustered in the top right of this photograph are 19th Century German-milled stone.

We use these picture for illustration because we cannot imagine that Colonial marbles could have looked much different from these. Those marbles were undecorated stone and clay.

Marbles at Mount Vernon

In fact the larger stone to the left and about mid photograph does look remarkably like the single polished limestone marble featured on George Washington’s Mount Vernon website.

Along with the Mount Vernon photograph there is a short but informative note on Colonial marbles: “While it is always difficult to associate an archaeological item with a singular person, it is possible a toy such as this would have been used if not owned by one of the many enslaved children living and working at the Mansion Farm during George Washington’s lifetime. In 1799, the year of Washington’s death, 28 children under the age of 14 were living and working at the Mansion House Farm.

Objects such as this marble offer a glimpse into the ways these children and their families may have sought to reclaim their humanity in the face of dehumanizing practice of racialized slavery through the experience of games and play.”[12]

Marbles in the Revolution

Colonial children and adults did play with marbles all throughout the 18th century. And we know that marbles were played during the War as well. And with so many examples for sale online, we decided to try and get permission to use a photograph of Revolutionary War marbles from some appropriate museum online. After all, such Colonial repositories must be flush with them!

An Odd Bounce: New York Historical Society

Well…things did take a strange bounce at this point in our research. First, a number of people whom we wanted to speak with were on vacation for the summer. This is not odd at all and we will follow up if we can.

But at the New York Historical Society we did find a nice size frame where marbles were to be displayed. The frame. No picture. However, there was this notation written to accommodate the missing photograph: “These marbles were excavated by Reginald P. Bolton and others from a refuse deposit near military barracks that extended along Bennett Avenue between 181st and 182nd Streets. The barracks were built after the surrender of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, and were occupied by the British and Hessian garrisons of the fort until evacuation in 1783.”[13]

The Museum Responds

Wow! We would love to see the marbles and we wrote to the Museum to see if there was a digital image which had simply not been posted online. We quickly received this email from the Museum Department of the Society:

“I have searched our records for any photos of the fragments, but unfortunately, I was not able to find any. However, the fragments are here on-site at the Museum. Being that you would like to use the photos for publication, I would suggest connecting with our Rights & Reproduction department to place an order for photography of the fragments.”

Fragments? Oh, dear! But, in fact they do have hard physical evidence that the British and Hessian soldiers did play marbles, rolley, shooting, or 9 Men’s Morris or some other type board game in camp. And, of course, we did pursue the question in the Rights & Reproduction department. If we do get ahold of a photograph then we will return to this post and publish it.

Reginald Pelham Bolton

Another aside: we learned along the way that Reginald Pelham Bolton (1856 – 1942) was secretary of the Committee of the New York Historical Society in 1918.[14] We read Bolton’s report of “organized field work” for the Museum. We have read hundreds of formal archaeological surveys and field studies over the last quarter century. This is not at all what Bolton produced.

An online site called “My Inwood”[15] gives some flavor of the Bolton field explorations: “Starting sometime in the 1880’s a group of “Weekend Archeologists” began exploring the virgin soil of Inwood, on the northern tip of Manhattan, with pick and shovel.

Often these gentlemen of a Victorian era and dress had no idea what they were looking for. They were intelligent men, armed with maps, sketches and books, as well as an acute awareness of the area’s historical significance.”

How Unusual

And this from Bolton himself: “One of our party is a born joker, and he made a sly snapshot of me while we were digging out a skeleton when I happened to be eating a sandwich, while holding the deceased’s leg bone in the other hand. Then he had a stereopticon slide made of the scene and slipped it in among my pictures when I was giving a lecture. You may imagine how I felt when I was shown up as a Cannibal before my audience.”

Astounding. Children and families visited the dig and participated. At the Fort Washington site, where a marble or marble fragments were dug, Bolton also dug thousands of buttons: “…many cannon balls, shells and bullets came out as we dug, and with them much broken china and porcelain, beautiful old bowls and plates and cups which we patch together during the winter.”

We have gone through digital reports from the New York Historical Society and we have not found one word, nor a field photograph, of a marble.

Another Try: Museum of the American Revolution, Philadelphia

Next we turned to another logical place to find Colonial and Revolutionary War Marbles: Philadelphia. Philadelphia was the capital of the United States for much of the colonial and early post-colonial periods. It was also the capital in 1790 – 1800 while the capital city was built in the District of Columbia.

We visited the Museum of the American Revolution online and highly recommend a visit either online or in person![16] Odd, no marble photographs were online. In response to our email we learned from a curator that the Museum does not have Revolutionary marbles in their collection. Now, this was a surprise!

The End of the Rope?

Along with contacting New York and Philadelphia we made digital contact with the Smithsonian Institution and even Museums overseas. No luck finding a Revolutionary War-era marble. If we learn anything later then we will share. But here is what we learned:

Both adults and children played marbles throughout the American Colonial period.

It is reported by the National Park Service that marbles were the most important toy at the time.

Marbles, clay and stone, were used in shooting games like Ringer as well as a type bowl/roll into a hole.

Marbles were popular game pieces for games such as 9 Men’s Morris. This game was easily portable, very light to carry, and it lent itself well to improvisation.

Children at the time loved marbles for many different reasons and children’s marble play cut across racial and socioeconomic lines.

Revolutionary War soldiers from different armies played marbles in camp. To our knowledge, no one has yet excavated a 9-Men’s Morris or similar board game.

Soldiers improvised when playing marbles and the ball from ball and buck ammunition was also used for play. Who can say that dropped bullets found in Revolutionary War camps were used, not as munitions, but as game pieces.

Okay, while we are to the end of the rope for now but we aren’t typing the proverbial knot in it just yet. We may hear back from someone who has primary Colonial and Revolutionary War evidence for us. Do you?

Note: Additional photos and research are at the end of this post. Please scroll down for updates.

Review:

“Another wonderful article Larry. You have a nice nose and a good pen. And what are you looking for all that well.” Wendy Leyn, Zandvoorde ,West Flanders, Belgium

Footnotes

- Thomas, Isaiah, Printer, and Miniature Book Collection. A little pretty pocket-book: intended for the instruction and amusement of little Master Tommy, and pretty Miss Polly: with two letters from Jack the giant-killer, as also a ball and pincushion, the use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good boy, and Polly a good girl: to which is added, A little song-book, being a new attempt to teach children the use of the English alphabet, by way of diversion. Printed at Worcester, Massachusetts: by Isaiah Thomas, and sold, wholesale and retail, at his bookstore, 1787. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22005880/>. ↑

- You can see a certificate of authenticity @: https://www.faganarms.com/collections/miscellaneous-antiques/products/revolutionary-war-clay-marbles-4?_pos=1&_sid=331dc2ea5&_ss=r (7/22/2023). Another online site advertises a lot of Revolutionary War marbles in part as: “These Revolutionary War Continental Army camp marbles were excavated and dug from a historically recorded Colonial Army encampment in New England. These 10 handmade clay stone marbles were used and played with by Revolutionary War Colonial soldiers fighting the British.” If interested check out early Colonial American Revolutionary War era marbles at the Smoky Mountain Relic Room in Sevierville, Tennessee: https://www.therelicroom.com/product-page/early-colonial-american-revolutionary-war-era-marbles (8/4/2023). You can buy one of these marbles there for $3.00! ↑

- You might want to check this which was published by the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia: “Big Idea 3: Soldiers of the Revolutionary War” @ https://www.amrevmuseum.org/big-idea-3-soldiers-of-the-revolutionary-war (8/2/2023)↑

- https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/ 8/4/2023 ↑

- https://hylandhouse.wordpress.com/at-home-activities/nine-men-morris-game/ 7/22/2023↑

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nine-Mens-Morris (8/6/2023) Simple game, right? Well, perhaps when you have spent dozens if not hundreds of hours on the board it becomes second nature. Different versions of the game are readily available online. ↑

- https://grammarist.com/idiom/knuckle-down-and-buckle-down/ 8/6/2023 ↑

- “The age-old game of marbles” by By JAMES W. SPAIN For the Concord Monitor Concord, NH: Published: 1/27/2021 https://www.concordmonitor.com/a-simple-marble-38462453 8/1/2023 ↑

- https://www.refinerofgold.com/marbles/games/history.html 8/6/2023 ↑

- We tip our hat to Melina Mercouri & Jules Dassin in the 1960 movie of the same name. ↑

- “5 Things You May Not Know About Marbles” https://blog.cmog.org/2022/02/15/5-things-you-may-not-know-about-marbles/ 8/1/2023 ↑

- https://www.mountvernon.org/preservation/ (8/7/2023). The Mount Vernon website is extraordinarily well constructed and it even includes information on the prehistoric peoples who lived in the area before the Mansion was built. It at all interested in history, preservation, or archaeology then we strongly recommend that you visit the site. ↑

- https://emuseum.nyhistory.org/objects/35677/marbles-3-excavated-at-revolutionary-war-barracks (8/7/2023) ↑

- Bolton, Reginald Pelham. “The Field Committee of the New York Historical Society.” pp. 39 – 42. A description of the Society’s first organized field work at “Indian, Colonial, and Revolutionary Sites.” ↑

- https://myinwood.net/historical-explorations-in-new-york-by-reginald-pelham-bolton/ 8/8/2023 ↑

- https://www.amrevmuseum.org/ 8/7/2023 ↑

Update from Williamsburg

After we posted this story we did hear from Williamsburg. We want to thank Ms. Marianne Martin, Visual Resources Librarian at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. She provided the following photographs and they provided new avenues for research.

Below is an update to the story.

Enslaved Children’s Marbles found in the Root Cellar

These clay marbles were excavated from the root cellar of the home of an enslaved family at Carter’s Grove Plantation in Virginia.[1] Carter’s Grove is on the James River and it is downriver from Jamestown. It was built from 1750 – 1753 by brick mason David Minitree and, some sources report, architect Richard Talieferro. The Plantation, near Williamsburg, Virginia, originally covered some 1,400 acres.[2]

These marbles were found in the slave houses which were about a quarter mile from the plantation house at Carter’s Grove. We were very pleased when we studied the topic of subfloor pits in the enslaved quarters to learn that the topic of the daily lives and contributions of the enslaved families in the Colonial Williamsburg area have been given full attention since at least the early 1990s.

What’s in the Pits?

Patricia Samford[1] makes the case that these pits were root cellars and storage areas for the enslaved families. Since at many sites little remains of the homes which were over the pits, some scholars have been slow to accept that these were root cellars.

We have read that some of these pits also contained one or more enclosures which appear to have served as “safes” where the families could store personal possessions.

These pits, at Carter Grove and nearby plantations, have yielded a wealth of information about the life of Colonial enslaved families. As would be expected, archaeologists have recovered an abundance and wide range of ceramics in the pits.

But at the Palace Lands (1750 – 1775) in Williamsburg[2] scholars also dug a doll part and at least one marble. We cannot be sure, but we believe that this marble, like the ones from Carter’s Grove, was made of clay.

Pits dug at Palace Lands, Ferry Farm Structure C (1760 – 1775), and at Poplar Forest – North Hill (1770 – 1785) all contained shot. Palace Lands also yielded a gun flint. This supports the evidence collected which indicates that at least some enslaved people did hunt to supplement their diets.

Coins were found at all three of these sites. A quartered and drilled Spanish coin was found at Ferry Farm. Other finds include a crystal, knives, and scissors and thimbles.

We are pleased that we can add this photograph and these notes to our post. Enslaved peoples played critical roles all across the South in the Colonial period. And we are proud that the homes of enslaved peoples are being investigated by archaeologists and other specialists and that the history of slavery is being incorporated into the presentation of “mainstream” history.

Look at that tiny marble ring! [7]

References

1Clay marbles excavated from the root cellar of the house of an enslaved family at Carter’s Grove Plantation, OBJ-508D-00321, image #1996-TEG-315-8s

2 You can read more about the Plantation @ https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/carters-grove 9/15/2023

3 Carter Burwell (1716–1756) @ https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/burwell-carter-1716-1756/ (9/16/2023). You might also want to study the “Alphabetical List of Robert Carter’s Slaves Compiled from the 1733 Inventory of his Estate” @ https://christchurch1735.org/robert-king-carter-papers/html/C33slaves.html 9/16/2023

4 Samford, Patricia. “Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series – 1629” Originally entitled: ” Carter’s Grove Slave Quarter’s Study” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1988 & 1990. @ https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR1629.xml&highlight 9/16/2023

5Documentation and Evidence for Proposed Implementation of Phase 1 – B of a Landscape Rehabilitation.” You may also want to read Brown, Patricia Leigh. “Restoring a Past Some Would Bury.” The New York Times September 12, 1988 @ https://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/12/restoring -a-past-some-would-bury.html/ 9/16/2023

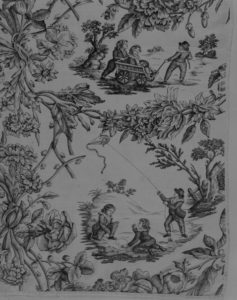

6Lower left register, Plate 5 of Basedow, Johann Bernard, Kupfersammling zu J.B. Basedows Elementarwerk fur fie Jugend und ihre Freunde, Berlin, Germany, 1774, accession #SCRB011983, image #1976-1332

7Detail, Textile Copperplate Print, England, 1780-1790, cotton, accession #1955-323, 1 image#1958-DW-2163