1907, 0119.38 © The Trustees of the British Museum, Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license[1].

Woops, we did it again![2] We have always been interested in history, archaeology, anthropology, and ethnography. We also love to explore and to discover new places. We often add to our store of researched and interesting ideas by exploring digital galleries online in museums worldwide. For examples, we enjoy browsing the Victoria and Albert museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution, The British Museum, and local museums and institutes worldwide.

Because of this, all of our “marble stories” are set in the larger context of one or more of our interests. We have researched and published stories about the historical place of children, child’s play, toys, and marbles in cultures worldwide and across time. And we have discovered that some marbles do have a secretive, and often mysterious history which is anything but clear-cut…as is the case with this look at Minoan Marbles which started with a stroll through digital records held by the British Museum.

The bright red-orange .87” – one inch ball which is the feature photograph for this story is listed by The British Museum as a “ball marble(?)”. With a question mark? We are confident that the Museum uses the question mark on other artifacts. But, we don’t remember ever seeing such an open question on a Museum holding before.

There was an image of a second Minoan ball. It looks different but shares the same context. So, what do we have here?

The Changing Nature Of Archaeology

It was these two dramatic photographs that first captured our attention, but it was that question mark that hooked us. We quickly learned that the balls/marbles were acquired by The British Museum in 1907 and that they were donated to The British Museum by the British School at Athens, [BSA] Greece. This meant that they were found or dug on the cusp of archaeology as it transitioned from a classical academic study to a scientific, and often rigid, science.

“After mid-century [1850], archaeological spectacle gave way to more systematic forms of engagement, and it became possible to discern the contours of a discipline, including specialist publications, professional organizations, and formal curricula.” [3] (Emphasis Added)

Our story In The Shadow of The Tomb: Marbles From the Guldara Stupa was set in this tumultuous period of British exploration and the flexing of British nationalism and military might in both Afghanistan and India. That story is a harsh reveal of one attempt at Victorian archaeology in such a volatile environment.

The Victorian Web further explains that “by 1883, archaeology was no longer one topic among several but a complex subject with distinct sub-specialties. At Cambridge, late Victorian archaeology encompassed art, history, mythology, and religion, in addition to ancient languages.” (Emphasis Added) We cannot imagine such a curriculum for archaeology students today! The University of Cambridge (founded in 1209) and The University of Oxford (founded in 1096) set the benchmarks in learning and research for centuries.

The British School In Athens

In 1907, the British Museum in London acquired the marbles from The British School (BSA) in Athens, Greece. The School has Victorian origins having been founded in 1886. Originally it was housed in only one building, but it has grown exponentially over the years. The BSA has expanded to include a hostel, an extensive library, a substantial archive, and the Marc and Ismene Fitch Laboratory for science-based archaeology. (Emphasis Added)

The Marc and Ismene Fitch Laboratory, established in 1974, has been instrumental in advancing science-based archaeology, particularly in the study of ceramics. The BSA also maintains a research center at Knossos, which grew out of the estate created by Sir Arthur Evans, the site’s first British excavator[4].

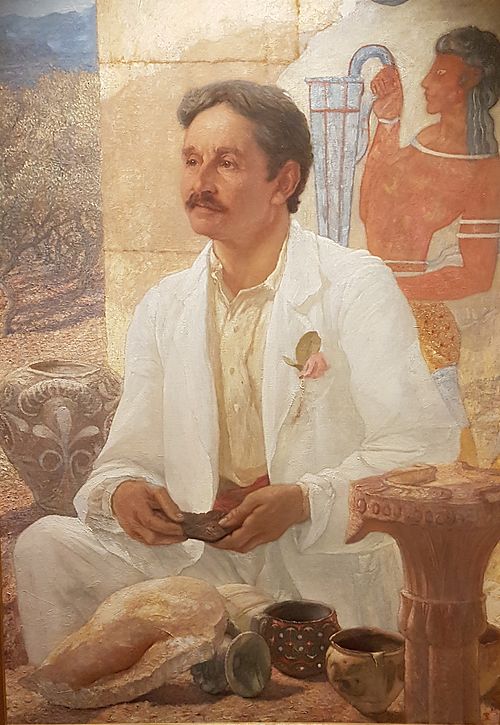

Sir Arthur Evans: A Prime Example of A Classical Academic

This portrait of Sir Arthur (1851 – 1941) was completed in 1907 which is late in the Orientalist art period. While highly romanticized, the portrait does give us a very interesting image of Evans at about the time of his digs at the Palace of Knossos.

It is said to show Evans in the ruins of the archaeological digs at Minoan Knossos in Crete, Greece. Knossos is shown near Heraklion on a map below. Evans started to dig here in 1900. His portrait also appears to show Evans as an archaeologist ceramicist, or one who is very interested in ceramics or pottery found on dig sites.

We can only imagine how many shards of earthenware he dug in the 1,300 rooms in the Palace of Knossos but he also found sophisticated frescoes and an advanced drainage system. It is important to note that Evans purchased the Palace before he dug! That’s certainly one way to gain permission to dig! “The main excavations, involving between 50 and 180 labourers, took place over the next five years, followed by conservation and, more controversially, reconstruction work. The main excavation report, The Palace of Minos, was published between 1921 and 1936.[5]”

More Leads From The Museum Entry

The BSA, and not Sir Arthur, donated the votive balls to the British Museum. We did learn that both marbles date to the Middle Minoan I and II Periods (2000 BC – 1700 BC), and that both were made in Crete and found at the Cretan Peak Sanctuary at Petsofas.

While both marbles were made of local clays, the clay appears to be very different for the two marbles. From what we can tell, this second marble is less carefully made than the first and it is made of darker clay.

On the other hand, it may not be made of darker clay and may not be a marble at all! Was it once painted? The British Museum entry for this second marble reads: “The ball was found in a Minoan peak sanctuary suggesting that it was a votive offering rather than part of a game.” (Emphasis Added) Where did these Minoans live? What is a peak sanctuary? And what is a votive?

When in Crete…

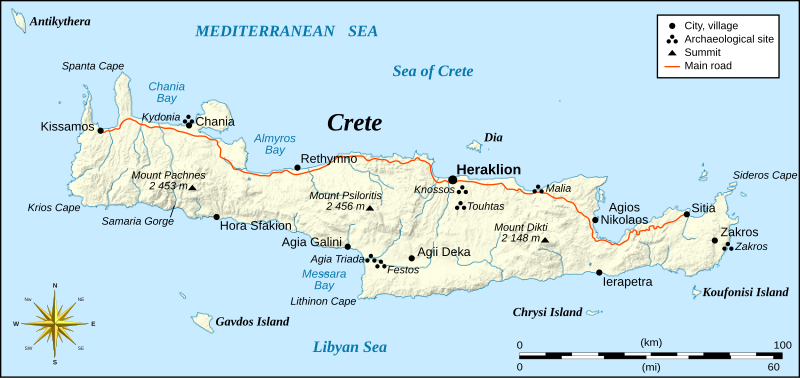

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands. It is located in the eastern Mediterranean Sea and it has stunning landscapes, a rich history, and a vibrant culture. The island also has a diverse geography, featuring rugged mountains, fertile plains, and gorgeous beaches like the “pink beach” at Elafonissi.

It was home to the Minoan civilization, one of the earliest advanced societies in Europe, dating back to around 2700 BC. Over the centuries, Crete has been influenced by various rulers, including the Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, and Ottomans, each leaving their mark on the island’s architecture and traditions[6].

Eric Gaba – Wikimedia Commons user: Sting

Eric Gaba – Wikimedia Commons user: Sting

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Reusing_content_outside_Wikimedia/

What Is A Cretan Peak Sanctuary?

Minoan peak sanctuaries are widespread across the island. Most scholars agree that peak sanctuaries were used for religious observances high in the mountains. Human and animal figurines, as well as signs of religious architecture, have been found at most peak sanctuaries. Additionally, clay human body parts are found at many of these sites[7] as well as zoological figurines of a wide variety of animals.

Crete has a number of mountain ranges including the Dikti, White Mountains, and Mount Ida. There are also karst topography and limestone formations with natural caves and clefts where worshipers leave small figurines, bowls, and a wide range of artifacts.

Sanctuary “…peaks were strategically chosen based on their visibility from settlements, their prominence in the landscape, and their accessibility. Many sanctuaries were not necessarily on the highest peaks but rather on the most visually striking summits—ones that appeared dominant when viewed from below. This ensured that they were symbolically powerful and possibly served as beacons for communal gatherings.[8]”

What Kinds Of Offerings Are Found?

In our Minoan research we generally find descriptions of all of the thousands of human and animal clay and metal figurines and these are generally prominently displayed in museums world-wide.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of human body parts have been found on the peaks. At Petsofas something like a model building with shapes like horns has been found and this may be a singular find. Terracotta rhinoceros beetles have been identified along with a fish and goat and a small boat[9]

Clay figurines and small vessels seem to be votive offerings.Many votive figurines found at Cretan peak sanctuaries were painted…. Small clay figurines of men and women were common offerings. Some of these figurines were painted in colors like reddish-brown and black, with details highlighted in white and red. Additionally, a terracotta votive figure…dated to the Middle Minoan period (2000–1700 BC), retains traces of black and white paint. These painted details likely added symbolic or decorative significance to the votives.[10]

Are These Artifacts Votives?

The word “votive” originates from the Latin votivus, which comes from votum (meaning “vow”). In historical and archaeological contexts, votive offerings were commonly used in ancient civilizations as acts of devotion or gratitude. And it was perhaps a natural extension of the concept, since so many clay body parts were carefully tucked away, that some of the figurines were placed in the ritual site as a petition for healing[11].

Past debates have focused on several issues which still remain open to question: 1) was there any organized pattern of votive offering deposition and any hierarchy in the distribution pattern? 2) were the votive offerings left complete at the spot after the ceremony or were they intentionally broken during it?; 3) was the cult place periodically cleaned of votive offerings and other remains, or did subsequent ceremonies simply ignore the items deposited earlier?; 4) were offerings in cups more common than figurines? [12]

Bodies of Clay

One of the most marked peculiarities of Petsofa is the series of detached arms, legs, and heads, modeled separately, and often perforated at the butt-end for suspension. The arms are usually given from the shoulder downwards, extended or somewhat flexed : they are colored either white (probably for women) or brown-red or black (for men); and they measure from 8 to 12 cm. from shoulder to finger-tip. One white one [41][13] includes, besides the whole arm, a full quarter of the trunk, and its suspension hole is at the angle of the latter nearest to the place of the neck. Others represent only the forearm; and one black one [42][14] which seems to have telescoped the whole arm, and indicates an elbow close to the wrist—has a large, vigorously modeled hand…. P. 374 EXCAVATIONS AT PALAIKASTRO. II.

This AI-generated leg has no hole at the top. Some were simply “cut off” like this one, but others had a sculpted top and a small hole through the clay. We often find Victorian German porcelain doll legs and arms with a hole at the top and a wire attached which allowed a child to articulate the arms and legs on her or his doll. We imagine that there would be parts like these Victorian dolls at Petsofa and maybe other peak sanctuaries across Crete.

Clay Balls

In his report about excavations in Petsofa, on page 379 J. L. Myers notes: “the only other objects which need record are :—.” We can only imagine that he meant that the only other objects which interested him at all—but we are unsure. The following are among the objects which he did care to enumerate:

“A very large number of small clay balls [66][15], from 2.5 cm [.99”]to 1.5 cm. [.60”] in diameter, well rounded, but without ornament or appendage of any kind.”

Is Myers saying that he found “a very large number” of marbles? If so, then this really changes the nature of the finds! One thing is for certain: “a very large number” is a great deal more than the two that we have images of from the British Museum. And what in the world could he mean about clay balls “without ornament or appendage”?

Just out of curiosity we asked Microsoft Copilot to sketch us an image of a votive Minoan ball as may have been found at Petosà. This is the sketch Copilot produced.

Since they were so plain, how could the balls we are researching be votives? The balls are described by archaeologist as being “without ornament”. We think that true votives might be fashioned out of different materials and decorated to fit the occasion, something like the one pictured above.

Remember The ?

Remember that question mark that the British Museum placed on one of the marbles? Well, Myers [16] was acutely aware that the marbles posed very real problems as votives. He describes them as aniconic spheres on page 381 of his EXCAVATIONS AT PALAIKASTRO. II.

The “aniconic spheres” are marbles! The term “aniconic spheres” isn’t used in archaeology today and it is hardly recognized. We think Myers was referring to aniconism, which is the cultural or religious practice of avoiding figurative representations of divine or supernatural beings. In some traditions, symbols or abstract shapes—such as spheres—might be used instead of direct depictions.

A Problem of Bias

There is a problem with bias here. Myers and several other classical academics essentially established the model and founding precepts of votive offerings at the peak sanctuaries in Minoan Crete. We have only their interpretation.

Calling the balls aniconic reflects the author’s education and teaching and his perspectives and biases influence the conclusions drawn from the data. The subjective nature of archaeological interpretation means that different scholars might arrive at different conclusions based on the same evidence.

We cannot imagine that a modern archaeologist, trained in the somewhat rigid precepts of best archaeological practices, would think first that these are votives. He or she would immediately compare the figurines to others found on Crete or elsewhere in the region. There are 25 peak sanctuaries scattered across Crete. Would all or some of the artifacts found at other excavations have been classified as votives?

Marbles or Votives?

We can understand the basic mental construct that if you had a problem with your arm or leg then you could buy or, if skilled enough, make a votive of what hurts and go and pray at the sanctuary for healing and then leave the appropriate votive behind. You could do the same if an arm or leg has healed properly—in this case you would give thanks.

But can you imagine what a sphere, and not a perfect one at that, could be used ritually? Well, we appreciate archaeology and historical analysis, but we have long felt that there is something lacking in the historic interpretation of the ritual artifacts. We are confident that as Myers sat inside the tent by lamplight and pondered on dig findings one critical aspect of Minoan society was never considered: children.

Children?

No, we are not claiming that the clay balls are toys and not ritual votives. But think about it this way

While there are obvious exceptions to the claim that archaeology is essentially childless, even the rare cases in which childhood has been central to archaeological inquiries have served to only further marginalize the children of the past. Children are regularly relegated to “peripheral roles” in these types of traditional archaeological analyses… I argue that this is because the archaeologists are reliant on an antiquated theoretical tool set when they are confronted with the often “unexplainable” presence of children’s artifacts in unexpected contexts.[17] (Emphasis added)

We can think of nothing in the peak sanctuaries more unexplainable than terracotta balls tucked away with the other artifacts.

Yes, Children

There were children in Minoan Crete. It was a child, after all, who found the artifact that attracted Myers to the peak sanctuary in the first place. We know that in Minoan society the sanctuaries were for everyone. They were open in more ways than one. There were no priest intermediaries through whom you offered your figurines. All classes, it seems, were allowed to place the artifacts where they preferred and for whatever their need or thanksgiving was at a particular time.

Did children accompany their parents up the twisting paths? Did they leave votives? Did they make votives either to leave by themselves or for their parents to leave for them? Were the balls part of children’s games?

To our knowledge no one knows. Perhaps no one ever will.

So we close. We have our own opinions about what happened on those barren slopes so long ago. Think about it. After reading this story you can form your own take on the topic. As always we would love to hear from you about any ideas you have on the subject.

More Browsing & Reading Suggestions

https://www.britannica.com/place/Crete

https://www.visitgreece.gr/islands/crete/

https://greekreporter.com/2025/05/24/ten-souvenirs-to-buy-in-crete/

https://historyandarchaeologyonline.com/the-minoan-gods-and-their-sacred-places/

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1907-0119-15

Litster, Mirani, and Michelle C. Langley. “Is It Ritual? Or Is It Children? Distinguishing Consequences of Play from Ritual Actions in the Prehistoric Archaeological Record.” Current Anthropology, vol. 59, 2018 & @ https://www.academia.edu/37405301/Is_It_Ritual_Or_Is_It_Children_Distinguishing_Consequences_of_Play_from_Ritual_Actions_in_the_Prehistoric_Archaeological_Record/ 5/4/2025

References

- A special thank you to Lucia Rinolfi, Account Manager, British Museum, Image. ↑

- With a node to Britney Spears. ↑

- Diane Josefowicz, “Introduction to Victorian Archaeology: Archaeology as a Discipline.” @ https://victorianweb.org/history/archeology/intro4.html/ 6/5/2025 ↑

- https://www.bsa.ac.uk/ 6/9/2025 ↑

- https://www.world-archaeology.com/great-discoveries/knossos/ (6/8/2025); “Perhaps the most controversial aspect of his work was his decision to restore the Bronze Age palace, in use from around 1900 to 1350 BCE, using modern building materials.” Restorations have continued on site and now Evans reconstructions need restoration! See Andrew Shapland. “How Knossos was Transformed Rebuilding The Palace of Minos.” Ashmolean Museum Oxford @ https://www.ashmolean.org/article/rebuilding-the-palace-of-minos-at-knossos (6/8/2025). You can buy a copy of The Malace of Minos from Amnazon @ https://www.amazon.com/Palace-Minos-Cambridge-Collection-Archaeology/dp/110806308X 6/8/2025 ↑

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Crete (6/10/2025) & https://www.visitgreece.gr/islands/crete/ 6/10/2025 ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minoan_peak_sanctuaries 6/10/2025↑

- A.A.D. Peatfield. “The Topography of Minoan Peak Sanctuaries.” Cambridge University Press, 27 September 2013 @ https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/annual-of-the-british-school-at-athens/article/abs/topography-of-minoan-peak-sanctuaries/FD85F5C56481A603087B43BEC4623144 (6/10/2025) & “Juktas Peak Sanctuary.” Minoan Crete Bronze Age Civilisation.” @ http://www.minoancrete.com/juktas.htm/ (6/10/2025). It is interesting that this online article about Juktas, which is south-west of Knossos and which serves as the peak sanctuary or open-air sanctuary for Knossos, does not mention votives! ↑

- Laura Perry, “Minoan Peak Sanctuaries: Pilgrimage and Offerings.” March 24, 2022. ↑

- Votives of this nature were left at religious sites across Crete. They were made of medal and terracotta and both materials were sometimes painted. Note the woman’s uplifted arms. We will not go into such ideas as whether or not a seated female figure or a female with uplifted arms like this imagined one does or does not represent a goddess. However, Knossos website tells us that “the Goddess with Upraised Hands figurines offer valuable insight into Minoan spirituality and religious practices. Their raised arms, head adornments, and presence in sanctuaries suggest roles in worship, fertility rituals, and divine manifestation.” We think it is fascinating to see the terracotta votives on this Knossos site and to compare them to the AI image! @ https://knossos-palace.gr/goddess-with-upraised-hands/ 6/15/2025 ↑

- A plain sphere seems like an unusual votive offering at a Minoan sanctuary. But we know that sometimes individuals themselves made the figurines while at other times people purchase an “appropriate offering at small shops. The figures, as a general rule, were skillfully made and painted. We have no idea what a purchased votive might cost, but we are certain that some people made simple offerings and even used polished pebbles. May a nice round marble was easier to make using the local clays in the valley. In many ancient cultures, simplicity carried deep symbolic weight. If in fact these are votive offerings then they were gifts made to deities in fulfillment of a vow or as an expression of devotion. While some individuals could not afford nor could they make a complex offering with arms and legs attached, we are confident that some votives were deliberately simple. Like a plain round marble which could represent wholeness, eternity, or cosmic unity, making it a powerful offering in religious contexts. To the Minoans a sphere’s symmetry might have been seen as an ideal form. Additionally, if the offering was made of a significant material—such as clay, bronze, or precious metals—it could still hold spiritual value despite its plain appearance. Check https://roman.mythologyworldwide.com/the-significance-of-votive-offerings-in-roman-worship/ 6/18/2025 ↑

- Nowicki, Krzystof. “CRETAN PEAK SANCTUARIES: DISTRIBUTION, TOPOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION OF RITUAL.” Archeologia (Poland) 67 2016-2017, 2018, pp. 26-27.PDF

- “Both delicacy and elegance of design, material, and technique are basic characteristics of all Minoan art & particularly of Kamares pottery. What is more delicate than the eggshell Kamares cups? What is more elegant than the harmonious curves of both shapes and decoration of Kamares vases?” See an example @ Kamares style – Spirit Of Greece 6/18/2025 ↑

- This number refers to the sketched illustrations “Terracotta Figures from Petsofà: III, Votive Limbs. No page number, in Myers paper J. L. Myres (1903). Excavations at Palaikastro. II: § 13.—The Sanctuary-site of Petsofà. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 9, pp 356-387 doi:10.1017/ S00682454000 PDF ↑

- This number refers to the sketched illustrations in “Terracotta Figures from Petsofà: IV, Animals, Vessels, &c”, no page number, in Myers paper J. L. Myres (1903). Excavations at Palaikastro. II: § 13.—The Sanctuary-site of Petsofà. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 9, pp 356-387 doi:10.1017/ S00682454000 PDF ↑

- The “difficulty” Myers speaks of is the difficulty in assigning votive meaning to a marble! Frankly, we have almost as much difficulty assigning votive meaning to a fox, a cat, weasel, hare, tortoises, birds, “crouching pigs” a calf, and even a tree! A

- Daniel Klear,. Towards an Archaeology of Childhoods. Pdf ↑